What the Japanese Bayberry Trees Have Seen Stories from the Early Years of Yamaha Motor

24Building the Factory

On October 22nd, 1954, we booked use of a runway at a Hamamatsu airfield to run the Ministry of Transport’s certification tests for the YA-1. The results showed that the new machine had excellent acceleration and braking, and set a top speed of 76 km/h. The bike set some very high performance numbers for the time. In fact, the test went so well that everything was done after only two hours, something also very rare back then. From such events, you can get an idea of what the general level of motorcycle performance was in those days.

Praise of the bike’s performance gradually spread, giving the sales teams and dealers more confidence in the new machine. Naturally, the expectations and pressure only went up for those in manufacturing.

As a result, the Komatsu Factory that had been nothing more than a warehouse for storing machinery had to be quickly transformed into a factory for production, so I ended up spending almost all my time from autumn onwards there.

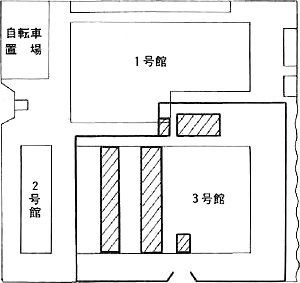

The factory buildings at the time (in 1955)

The factory buildings at the time (in 1955)The factory site at the time was inside the bold lines.

Part of the Hamamatsu factory today (in 1978) shown within the fine lines.

I’ve been calling it the “Komatsu Factory” because that’s what we called it since it was near Enshu-Komatsu Station, but that isn’t the official name since it was actually located in the Nakajo area of Hamakita Town. Accordingly, once the factory was up and running it would come to be called the “Nippon Gakki Hamana Factory.”

During the war, the site was originally owned by Yamashita Ironworks, a company located in Hamamatsu that was a sub-contractor for Nakajima Aircraft Company. They had purchased the land and built a new factory there to expand their operations. It was run by a company called Daito Kiko Incorporated, and I heard they machined pistons for airplane engines.

It was during that period that I saw many bayberry trees planted on the factory grounds; they were common in that neighborhood.

After the war, Daito Kiko started building hot-bulb engines for fishing boats. The pistons and cylinders they made for those engines supposedly had bore diameters of about 40 cm.

In the summer of 1946, the occupation authorities ordered Daito Kiko to cooperate in the destruction of the partially completed propellers and related materials at the Sakura Factory. Working day and night, milling machines, shapers and saws were used to chop them up.

Shortly thereafter, in an effort to downsize its operations, Daito Kiko was broken up into Tokai Fibers, Yamaya Brewery and Enshu Fibers. In the end, they also sold two of their main factory buildings to Nippon Gakki. Nippon Gakki moved the machines from the Sakura Factory and stored them in these recently acquired buildings.

Our job was to transform what were essentially abandoned warehouses surrounded by weeds and bayberry trees into a modern motorcycle manufacturing facility. Naturally, this task was Herculean in magnitude, but it was also very rewarding.

25Preparations for Marketing and Production

The sales team worked to mobilize the staff at Nippon Gakki’s branch offices and gradually secured several interested dealerships to handle the YA-1. Expectations were for sales of approximately 200 units per month and the dealers grew very enthusiastic about the new machine and wanted to get them in stock and start sales as soon as possible.

In preparing for production, the Efficiency Department organized the process planning and layout of the factory. The personnel that had completed product design work were put in charge of designing the jigs and tooling as well as arranging for outsourcing and more. We simply had no choice but to have them see to innumerable other tasks.

A Japanese bayberry tree at the Hamakita Factory today (in 1978)

A Japanese bayberry tree at the Hamakita Factory today (in 1978)The plus-side of a relatively small organization like ours was that it was much like a family. I feel those like myself who were fortunate enough to have experienced this era of the company firsthand might consider such an environment a blessing.

But my biggest challenge was putting together the teams of technicians. Also, although this would be for machining and factory work, we had already set a policy on hiring women. We put up wanted ads within Nippon Gakki and the roughly ten women who passed the aptitude tests began their training to use the turret lathes. We were unsure of how well we would do using the “training within industry” method for them, but we decided to take on the challenge anyway.

We also looked for machine operators and finishing technicians from outside the company and we were fortunate to acquire many talented people. Our aptitude tests were quite stringent; I think only one applicant in ten typically passed. Consequently, those that made the grade were the cream of the crop, and many of them now hold important positions within the company.

Most of the managers on the factory floor were from Nippon Gakki’s metalworks and tools departments, and many of those chosen were from among young people with no previous managerial experience.

In spite of these efforts, there was still a shortage of experienced machinists so we hired a number of retirees from the tools department of the Japan National Railway to work part-time. They were of great help.

As our workforce slowly came together, the issue of salaries came up and became a conundrum for us. At the time, workers at Nippon Gakki were paid according to a performance-based contract system to improve efficiency and their bonuses came from commissions.

But we didn’t know how best to pay the motorcycle workers and there was much heated discussion on this topic. However, I think President Kawakami had a long-held dislike for the contract system. He thought it best that we discard the less attractive contractual system and place our full trust in the employees in the motorcycle division by paying them a fixed salary—and that’s what we did.

On December 1st, after carefully considering our procurement situation and related issues, we decided on monthly production volumes of 20 units in January, 100 in February, 150 in March, and 200 in April. We were also able to sign contracts with twenty brand-exclusive dealerships throughout Japan.

26The Hamana Factory

Operations at Nippon Gakki’s Hamana Factory began on January 1st, 1955 and this also marked the formal start of the company’s motorcycle business. Thanks to the immense efforts of everyone concerned, we somehow got most of the work done by the end of 1954 and the building looked like a proper manufacturing facility.

Although the scale of the factory was still rather small, a variety of measures were taken to make sure it conformed to President Kawakami’s desire to create a model factory that was clean, efficient and well-organized.

The Hamana Factory in January 1955

The Hamana Factory in January 1955First and foremost, the floor was to be kept clean. A policy was adopted for the workers which required that they not bring dirt into the factory and that they treat it like their own living room. Outdoor shoes were removed at the factory entrances and clean indoor zouri sandals distributed by the company were worn inside.

In the crankcase machining and engine assembly areas, the floors were completely covered with soft wooden flooring—this was often criticized by gossipers for being an unnecessary extravagance—so as not to scratch or dent the aluminum parts.

When we planted grass lawns around the factory buildings, we were instructed to keep them 10 cm below the level of the roads and pathways to prevent mud from flowing onto them when it rained.

The exteriors of the factory buildings were painted white, which transformed their appearance. The contrast between the white buildings, green lawns and bayberry trees made for a very attractive scene.

Inside the buildings however, production work was very trying; anything and everything had to be made from scratch so there’s no way things would go smoothly. We had trouble producing parts that could pass quality checks and the production target for January had to be abandoned. Although we somehow met the 100 unit target for February, it was after a seemingly endless cycle of desperate struggles and perseverance.

Going home before ten at night on any given day was a rarity; we spent more time at the factory than we did at home. The lack of industry knowledge in general was palpable and made its own fair amount of contributions to our setbacks. One time, one of the guys in sales mistook the mufflers we were making for the mufflers you wrap around your neck when it gets cold.

After much back-and-forth discussion, a final suggested retail price of 138,000 yen was set. And that was if it was paid for in full with cash. Competing 125cc class motorcycles at the time were selling in the 110,000 to 120,000 yen range, so our price no doubt raised eyebrows and sent eyes popping out of their sockets. Many of us wondered if the bike would even sell at that price.

But as the manager of the Manufacturing Department, before we could worry about sales, we first had to produce the machines! In spite of all the effort and running around we did, we couldn’t get the first batch of YA-1s finished and production in full swing until January and early February.

This was a very trying time of sleepless nights, endless stress and extreme exhaustion.

27Birth of the Red Dragonfly

When we told the president that there was no way we could meet the January production goal and tried to justify it, he didn’t hold back with his admonishment: “What do you mean we’re a month behind schedule?! We’ve got the capacity to produce 200 bikes a month, so you should be able to produce 50 a week! Figure out a schedule to get them off the line more efficiently. You can’t come up with production plans laden with such hopeful expectations, so stop injecting your optimism into them. And enough of this nonsense of making a few bikes and then stopping all production. I’ll give you until the 15th, but I want a system up and running for producing three, four or more bikes nonstop.”

Our ears were burning after this scolding, but the truth was that the machinery hadn’t been used in years and still wasn’t operating too well. This was one of our most trying hurdles at the time.

From about February 5th onwards though, we were able to begin assembling engines and chassis, although some had to be taken apart again and reassembled to get everything right.

Working even on our days off, on the 8th we assembled engines No. 1 and 2, but the stoppers for the shift cam plates were missing so they had to come apart again and it wasn’t until the 11th that the first machine was completed. That “first complete machine” actually used the No. 2 engine as well as the No. 2 chassis.

Coincidentally, motorcycle journalist Heikichi Ito was visiting the factory that day and we promptly handed the bike over to him for a test ride. He said the YA-1’s handling and stability was incredible because he was able to scrape the footpegs in the turns.

President Kawakami also rode the bike, pronounced it satisfactory and personally stamped the engine with the “No. 1” engraving. There weren’t many people in attendance and it was a very simple ceremony, but looking back, this was a very significant moment in Yamaha Motor history.

In another coincidence, that same day was Kigensetsu, a holiday during the war when we would celebrate the enthronement of the first emperor of Japan. It was abolished as a holiday after the war ended but later reinstated as “National Foundation Day.” So while it was just a weekday back then, it was a day all of us there will remember for the rest of our lives.

General Manager Takai then promptly hopped on the No. 1 machine and rode it to Renjaku-cho in Hamamatsu and delivered it to Yano Trading. In celebration, factory operations were temporarily halted and the approximately 80 employees all lined up on either side of the main gate and clapped until their hands hurt as the first YA-1 rode away.

As we watched the first Akatombo (“Red Dragonfly”) set off toward Hamamatsu, its beautiful exhaust note fading slowly away in the distance, we saw it carrying all our hopes, dreams and efforts valiantly towards an already turbulent and uncertain market, and to a future we could only guess at. I remember how it was an emotional moment for us all.

The following letter at the end of this series of entries was written by the author in June, of 1978 to new Yamaha Motor employees in their second month at the company. The atmosphere of Yamaha Motor at the time shows through his words.

In Response to Your Comments at the Welcoming Ceremony

Tomo Sugiyama, Director and Cost Planning Office Chief

Hello to all you new members of Yamaha Motor. I believe some two months have passed since you started working or training, and I’m sure you are taking to your tasks with fervor and resolve. On April 1st, the day you officially joined the company, I spoke with you for about two hours. I read with great interest every one of the responses you so kindly sent to me.

In spite of the auditorium being cold and the poor acoustics, I was very impressed that you listened so attentively, at your passion for Yamaha, your work ethic, and your youthful enthusiasm.

In fact, many of your letters taught me something in return, and caused me to reflect on my own views and ways of doing things. Although the purpose of my talk was just to share my experiences and not to demand that you “work hard” or “do your best,” your letters were filled with strong-willed phrases like, “I’m going to do everything I can,” and “Yamaha’s future is in good hands with us.”

The strong yen has made for a difficult business environment for Yamaha. But seeing and knowing first-hand that so many young people filled with energy and optimism are joining the company fills me with relief and delight.

Nurture the passion and spirit of your youth that you have now; never let it waver. Remember that adversity is the best teacher and don’t give in to struggles. Let’s work together to make Yamaha grow and prosper into the future.

- To those of you involved in product design and testing, remember that performance isn’t everything. The end-product must also be easy to produce in the factory and easy for the markets to accept.

- For you all working in the factory, strive to produce high-quality products at a low cost that can withstand the rigors of use in markets all over the world.

- And to those of you in sales, your tasks are to get as many people as possible to choose the high-quality products our factories create, and to be the pipeline for bringing the unfiltered voices of our customers back to the company.

I believe that you all create the foundation of the company’s future by carrying out your individual responsibilities. Be sure to take good care of your health, because work you are not yet accustomed to will sometimes be very demanding, both physically and mentally. Write new pages in Yamaha history as well as your own. And if the time comes when there is something you feel you need to say, please don’t hesitate to write me. I look forward to following your progress.