Days Gone By Stories from the Trailblazing Years of Yamaha Motor

18The Finishing Touches: Our U.S. Market Debut

My story got somewhat sidetracked, but around the time that the V4 prototype was completed, I thought we should begin gathering information on the U.S. market, so we hired an American market research and consulting firm to look into the country’s outboard market trends. In addition, I had several members of our engineering department visit the International Marine Trades Exposition and Convention (IMTEC) in Chicago every year to investigate product trends. Based on the information and data we got, we gradually firmed up ideas for our U.S. market product lineup. The results were generally as follows:

1. As a general rule, use our existing models for marketing smaller outboards of 30 hp or less.

2. Develop a new series of 3-cylinder engines for models between 40 and 90 hp (Yamaha was the first in the world to build a 3-cylinder 40 hp outboard).

3. Our big outboard offerings will be the new V4 and V6 developed as a series.

4. All models in the lineup with 40 hp or more will feature oil injection systems as standard equipment (Yamaha was the first in the world to offer this feature).

5. The 220 hp V6 outboard will use a computer-controlled engine (the first outboard of its kind in the world) combining Yamaha’s best technologies and be equipped with an array of attractive features.

6. Prepare all-new colors and graphics specifically for the U.S. market.

From the FTC complaint, the dissolution of the joint venture was becoming more and more likely by early 1981, so this plan was put in motion. By 1982, the courts had ruled in favor of the FTC, the joint venture was dissolved and we at long last had our chance to formally enter the U.S. market. The order was finally given to work toward officially announcing Yamaha’s entry into the U.S. outboard market in Chicago at IMTEC in the fall of 1983.

Despite having begun preparations well ahead of time, there was still a massive amount of work to do. We threw ourselves into product development and that made things just as hectic on the production side. As I mentioned earlier, the new V4 and V6 engines were so unlike anything we had built before that extensive preparations were needed to produce them. There were a whopping 12 new models in all, ranging from 40 hp to 220 hp, and we had to get the production infrastructure up and running all at once.

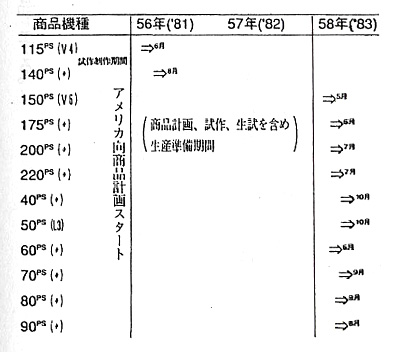

Everyone in the company poured tremendous energy into this project. As shown in the table, from June 1981 to October 1983—less than three years—we managed to go from development to production of 12 new models for the U.S. market. Never before had we accomplished such a colossal volume of work in such a short time.

The development and production schedule for 12 outboard models in 3 years

19Chicago and IMTEC in 1983

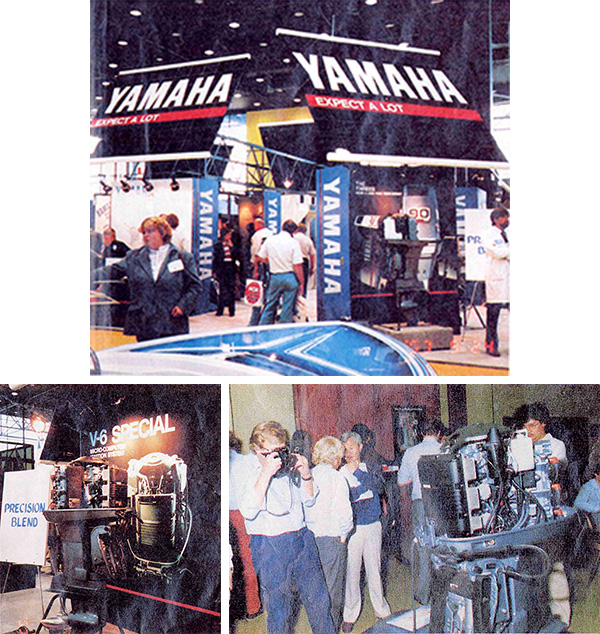

Yamaha made a stunning debut in the fall of 1983 at IMTEC in Chicago, displaying a full lineup of 20 outboard models ranging in output from 2 hp to 220 hp.

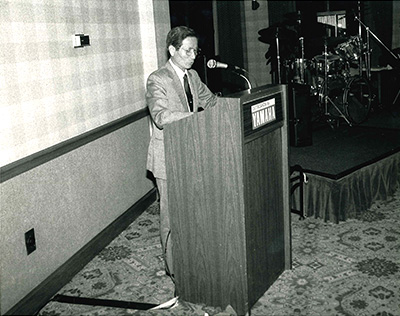

At a press day prior to the show’s opening, I made a short speech saying, “It has always been our dream to enter the U.S. market, the home of outboard motors. That dream has now come true and I invite you all to have a good look at our outboards.” I was full of emotion and extremely happy that our dream of many years was being fulfilled. The many difficulties and hardships we’d overcome made our joy all the greater; it was the kind of exhilarating satisfaction you can only feel after accomplishing something incredible.

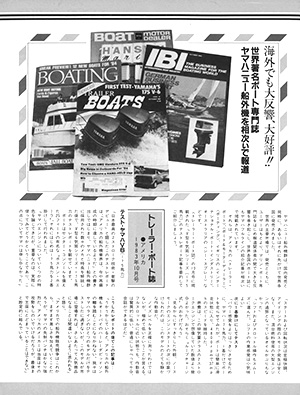

There was a crowd of people at the Yamaha booth that year. Our V6 engine equipped with a microcomputer and our oil injection system both drew a lot of attention and praise. One U.S. industry magazine featured a cover photo with a boat mounting dual 175 hp Yamaha V6 outboards, and the September issue of the well-known magazine Boating included a three-page article introducing Yamaha outboards titled “More Japanese Products Arrive.” Inside, the article said, “Yamaha’s entry into the U.S. marine industry provides a needed stimulation and will, over the long term, significantly benefit users and the industry.”

Yamaha’s V6 outboard was the first in the world to employ a microcomputer for controlling the ignition system, garnering significant coverage and acclaim at the Yamaha booth.

A 1983 article for marine dealers in Japan telling of the big response overseas to the new series of V6 outboards

Yamaha Motor Corporation, U.S.A. (YMUS) also worked very hard to get Yamaha outboard sales off the ground in the U.S. I have to mention Sylvan “Ham” Hamberger in particular. He was in charge of outboards at YMUS at the time and an expert on the industry. I’ll never forget how he went all over the country to get our outboards selling, and without his help, our entry into the U.S. market would never have gone so smoothly.

But while our American debut was spectacular, it was the work that followed that was tough. I remember how everyone at YMUS—Japanese personnel included—was on edge because they knew they had to secure results that would live up to the public interest and expectations we’d generated.

The author at the first U.S. marine dealer meeting in 1983

20Our American Baptism by Fire

We began selling our outboards in the U.S. the year following our debut at IMTEC in Chicago. Soon after and just as we’d expected, OMC filed a patent infringement suit with the International Trade Commission (ITC).

Three years prior to our debut in the U.S., our work turned toward checking existing patents and everyone in the engineering division thoroughly investigated the outboard motor patents held by American manufacturers. I believe there were around 750 of them. We also had the few patents we had some doubts about checked by American patent attorneys, so we were confident that we were in the clear; there was no way we were infringing on any patents.

The suit documents filed by OMC made four claims of patent infringement, but all four of them were among what we had previously investigated and we thought this all to be quite foolish. However, because the suit had already been filed, we would lose our ability to do business in the U.S. until things were resolved. OMC were insistent that our actions were damaging their business. Having decided that we would prevail if things went to trial, we began to contest the suit.

Yamaha Motor and Sanshin Industries formed a legal team consisting of three top American lawyers and two Japanese lawyers, and we began examining specific countermeasures. However, as things progressed the materials we needed to prepare for the case grew to enormous proportions, and the number of man-hours just to create them increased dramatically.

Yamaha Motor and Sanshin Industries organized a project team of more than 10 members to prepare the documents. But the more they worked, the more bogged down they became and the more difficult it became to find a winning solution. As the dispute dragged on, we began to realize that the reasoning behind this suit wasn’t simply about whether a patent had been infringed upon or not, but more about trade friction. Put bluntly, the patent infringement claim turned into more of an argument about how Americans were the first to build outboard motors and that Yamaha outboards were clearly similar to them. Furthermore, because the trial would be decided by a jury, we knew that the feelings of the American jurors would undoubtedly play a major role in any decision. We were also paying huge monthly fees to the lawyers.

For three months, each side argued their case but to no avail. I’m sure OMC must have also been paying enormous legal fees. It was then that talk of a settlement emerged. In the end, we agreed to pay a settlement to OMC and the case was over, but I think had the dispute continued, the time and fees involved would have become excessive. In retrospect, we were fortunate that all this occurred early on, because patent disputes with American manufacturers will likely increase in number and become more contentious in the future. I think it’s safe to say we’re now in an era where formulating patent strategies is no longer feasible armed solely with logical arguments.

21What We Learned in the Land of Recreation

Although I thought we had properly prepared for our entry into the U.S., when we finally did enter the market, we ended up facing several unforeseen problems, especially with our large outboards.

One example was overheating engines. When installing outboards on their boats, most users in America mounted their outboards higher up on the transom than normal to get higher speeds. This brought the inlet for cooling water near the water’s surface, meaning that it would sometimes even break above the surface when the boat was run. This resulted in inadequate circulation of cooling water and caused the engines to overheat.

Also, we learned that mounting the engines higher than normal caused the submerged lower unit and its torpedo-like shape to become improperly oriented. These were fatal flaws for big outboards as their focus was on delivering high-speed performance. A team of engineers flew to the U.S., investigated the problem and I put the entire engineering division to work on creating emergency countermeasures. These countermeasures were drastic and resulted in us even having to alter the die casting molds.

We had designed the shape of the propellers for an emphasis on performance, but turning the boat under certain conditions could cause cavitation, reducing propulsion power. When we looked into this, we discovered that propellers popular in the U.S. were all cupped, a downward curve machined into the inside trailing edge of the blade tips. In this way, big outboards marketed in the U.S. were built using various ideas and know-how based on how they were actually used.

These are all just a few examples, but after entering the U.S. market and becoming more aware of how our outboards were actually being used, we knew that we had to devise a number of revisions for our products. In the process of solving these all these small problems, we came to the conclusion that we really needed a test site in the U.S. This was partly because we couldn’t perform the kind of high-speed testing required back in Japan, and partly because we needed feedback from Americans who really knew how to have fun with boats, which meant that the cooperation of an American boatbuilder would be indispensable.

With the assistance of the American staff at YMUS, we began making detailed plans for building a test site, and in 1985, our high-speed test site was complete. The site is in Louisiana, set up along a diversion canal for the Mississippi River with testing taking place in the canal. The passage we can use is 70–80 meters wide, 2 km long, and the water is very calm, making it an ideal test course. And because this waterway is connected to a nearby lake, we’re able to perform various other tests as well. This test site plays an important role in improving the performance of Yamaha’s large outboards in the U.S.

A bird’s-eye view of our outboard testing facility built in Louisiana

The waterway we use for high-speed tests in Louisiana

22Success in the Market We’d Dreamed Of

Customers in the U.S. market often come up with creative ways of using their outboards to yield more performance, and small boatbuilders also have many interesting ideas that stimulate engine makers to come up with products in response. Factors like these energize the market to a significant degree—that’s the kind of market America is. It’s about always keeping a finger on the pulse of the market, grasping the trends and then reflecting them in your products. If you build products based solely on the ideas of your engineers, you will simply be left behind by the competition. In that sense, the U.S. is a wonderful market for outboards.

When we entered the U.S. market in 1984, the U.S. boatbuilding industry was just entering a boom that eventually lasted for five years, ending in 1989. These years were of extremely good fortune for Yamaha outboards as well. The high performance of Yamaha outboards became widely recognized, production numbers at Sanshin Industries increased and our lineup gained more large outboard models. Of course, sales and added value also increased significantly, as did company earnings. The U.S. had become one of the most important markets for Yamaha outboards, and our continued successes there eventually turned the Yamaha outboard business at Sanshin into a global leader in the industry.

Yamaha outboards presently occupy the number one spot for customer satisfaction in the U.S. In terms of outboard production volume as well, Yamaha is now part of a global triumvirate, standing alongside OMC and Mercury. And in March 1991, we reached a milestone four million Yamaha outboards in cumulative production since the company first began production in 1960. The road we took aiming to transform our third-rate products into first-rate ones, desperately striving to quickly catch up to OMC and Mercury, was long and arduous. But we had finally joined their ranks as one of the world’s leading outboard manufacturers.

Yamaha outboards reached four million units in cumulative production in March 1991.

A long line of Yamaha outboards in the U.S.

Looking back on the growth of Yamaha’s outboard operations, there were three major eras of development: the first was the joint venture with Brunswick, next was Plan N for building up the company’s annual production capacity to 300,000 outboards, and then Yamaha’s entry into the U.S. market.

The company president during each of these eras explained the goals that every employee should strive for in a specific, but clear and easy-to-understand manner. It was because everyone gave their all towards those goals that each was achieved. When one goal was reached, the next was shown in a way that anyone could understand, but more than that, it was presented in ways that inspired everyone to work towards the goal with great enthusiasm. I’m often acutely reminded of how important it is for directives to draw people in and drive their enthusiasm. Now, Yamaha’s outboard operations are turning to their next goal and once again the time has come for the company to muster its best to achieve it.