Days Gone By Stories from the Trailblazing Years of Yamaha Motor

23The Next Market: Stern Drives

Ever since Yamaha’s initial entry into the U.S. outboard market, I had been thinking the next marine product we should develop was a stern drive as it is the logical extension of an outboard. The U.S. was the main market for stern drives and the status of the market then was as follows:

1. In terms of market size, the number of stern drive units sold was only 28% that of outboard motors, but when comparing sales between the two, stern drives could reach up to 70% of total outboard sales figures—a significant sum.

2. There were only three active stern drive manufacturers, with Mercury at the top followed by OMC and Volvo.

3. A typical product lineup consisted of six to eight engine models ranging from 140 hp to 450 hp, with two types of drive units to mate with those engines. Compared to outboards, the number of products and parts required was far fewer with stern drives.

4. Demand for outboards had remained fairly stable, but demand for stern drives had been steadily growing for some time.

5. We could use Yamaha’s outboard development and production technologies for stern drives as well.

6. We could utilize the sales network and brand image of Yamaha outboards to our advantage.

7. We needed a stern drive to also help boost sales of big Yamaha outboards.

It was for these reasons that I thought we should begin building stern drives. As we did for our outboards, we first asked the market research firm we relied on before to conduct a detailed survey on stern drives in the U.S., the main market. Some personnel from the engineering division also traveled around the U.S. to get opinions directly from dealers and users.

What we learned was that many stern drive users placed even more importance on their boats than outboard users, and that they rarely used them at high speeds. As long as there was a good service network in place, they had little interest in outright performance. However, a lot of the feedback we got from users was that if Yamaha was going to bring out a new stern drive, they wanted a quality product different from what was already available.

What U.S. users meant by wanting a “quality product” was, in essence, engines more compact and lighter than the big and heavy ones already on the market. They also wanted a user-friendly product. Although it’s a more conservative market now, my impression then was that the stern drive market was ready and waiting for technological innovation. From this, we decided to build our stern drive engines with a power-to-weight ratio superior to any engine available on the market, and emphasized that both the engine and drive unit should be user-friendly with desirable features that set them apart from the competition. This was in late 1985.

24The Curtain Rises: The Boatbuilder Acquisition Drama

We first looked to see if we could use the V6 engine from our outboards. It was lightweight, compact and wouldn’t require investments to prepare for production. And if we produced more of them, the cost for outboards would also decrease. However, if we used it for a stern drive, we’d have to mount it horizontally because mounting it vertically like an outboard would make it quite tall and a bad fit for a typical boat’s engine bay. But mounting it horizontally also meant the positioning of the intake and exhaust systems had to be changed, requiring a complete redesign of the cylinder block.

If we were going to have to design a new engine regardless, we decided to go a step further and began considering a flat-six instead since it would offer a better layout and fit beneath the boat. Its lower height would allow it to fit under the rear seating area and result in much more available onboard space in the same size boat. This in turn would enable completely new interior layout designs and would be a standout feature that only Yamaha could offer. It was while building a prototype flat-six engine that we were convinced of the big advantages it offered for a boat’s layout. However, as we progressed with the project the final problem that remained was the price.

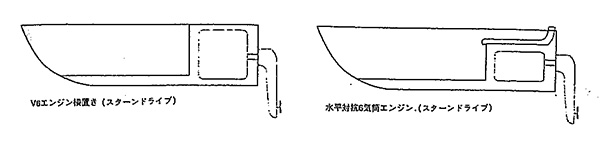

We examined several different engine types and layouts (left: V6 outboard engine; right: flat-six engine) while developing our first stern drive.

The engine being used by other companies was a General Motors (GM) truck engine designed 20-some years earlier and its incredibly low price made it a bargain. By comparison, our new flat-six engine would have to be built in limited numbers, and we just couldn’t get it to a level where it could compete with GM’s engine. We then checked to see if any of the DOHC engines Yamaha Motor’s Automotive Business Unit was building for Toyota’s cars were viable, but that route was also not cost-effective. In spite of all these setbacks, we still didn’t want to use a heavy, inefficient engine like other companies.

Our standstill state of affairs continued for some time, during which a major shift centered around stern drives occurred in the U.S. boating industry. For many years, Mercury had enjoyed almost complete dominance of the stern drive market, but then OMC announced their new Cobra line of stern drives in an effort to expand their market share.

OMC had managed to convince boatbuilder Bayliner Marine Corporation—Volvo’s primary contracted sales partner for their stern drives—to switch to their new Cobra series. Seeing this development, Brunswick subsidiary Mercury bought Bayliner outright and this in turn triggered a boatbuilder acquisition drama between Brunswick and OMC.

Numerous boatbuilders were bought up and made company subsidiaries at a fearsome pace. As far as stern drives were concerned, that meant almost half of the boatbuilders offering them became subsidiaries or affiliates of the two companies. The background for this was as follows:

1. It was boatbuilder profits that rose proportionally to boat sales increases, resulting in lower profit margins for the marine engine manufacturers, despite their greater financial and corporate power.

2. The entry of Japanese manufacturers intensified the competition between marine engine manufacturers.

3. Unlike with engines, Japanese manufacturers would likely not be able to enter the U.S. market for boats.

4. Selling boats and engines together as a package made things simpler and would help expand market share.

These factors drove OMC and Mercury to begin their acquisition spree, resulting in boatbuilders left and right becoming their subsidiaries or affiliates. Companies responsible for 35–40% of all U.S. market boat sales eventually ended up under the OMC or Mercury umbrella.

This all occurred over about a year and a half, and profoundly changed the role and positioning of both stern drives and outboards in the U.S. It even got to the point that there was concern boatbuilders unaffiliated with either company might no longer be supplied with stern drives or outboard motors at all. This resulted in growing expectations for a source other than OMC and Mercury that could provide a steady supply of stern drives.

25Signals of Impending Danger for Yamaha

I was contacted by YMUS; they had been keenly observing the situation and determined that this was our best chance to enter the market for stern drives. “If we don’t take advantage of this opportunity, this wave of acquisitions will continue and non-affiliated boatbuilders will end up having no interest in alternatives. Then there will no room for Yamaha to enter the stern drive market. We don’t need something different or amazing, we just need something we can offer...and quickly.”

It was around then that the development team in the engineering division was still agonizing over which engine to use. However, the overall concept for our stern drives had already been agreed upon. This called for a lineup consisting of two types of stern drives and three types of engines: a 4-stroke, 2-stroke and diesel. We particularly wanted to have a 2-stroke engine series for low-horsepower models since it would be a major feature of Yamaha stern drives. But developing the entire lineup simultaneously was simply impossible, so from a marketing standpoint, we had to figure out which developments to prioritize.

Step 1 was to pair one stern drive model with our series of four 4-stroke engines ranging from 140 hp to 260 hp. Since the main market for this 4-stroke engine series was the U.S. and procuring large-displacement base engines in Japan was difficult—and also since we were still facing several issues with building an all-new engine as I mentioned earlier—we decided that we had no choice but to use the readily available and market-proven GM unit for our base engine.

However, since it would be difficult to differentiate the power characteristics of our package using the same base engine as other manufacturers, we incorporated the latest technologies for the electronic engine controls to give it some features unique to Yamaha. Steps 2 and 3 were to expand our lineup to include more high-horsepower models, establish the diesel and 2-stroke series and eventually replace the GM engines with new lightweight and compact engines of our own and market them as new products. Under this overall plan, the four models from 140 hp to 260 hp in the first step were to be publicly announced as 1990 models.

However, as I wrote earlier, YMUS was very concerned about timing: “We’ll be too late with this plan. The product doesn’t have to have any special characteristics; we want it a year from now, otherwise we’re going to miss this perfect chance to enter the market here.”

But the development team at Sanshin had their own opinion. “It will take at least two years to make a product customers will be satisfied with,” they countered. “We’re not going to put out some half-baked product.” In the end though, it was YMUS’ stance that won out at a meeting of Yamaha Motor’s managing directors and we were forced to accelerate the start of production by more than a year than our plan originally called for.

26Japanese-American Stern Drives

With the decision made final, we put our full effort toward carrying out the plan. The workload the engineering and manufacturing divisions faced was immense. And even though YMUS said the final product didn’t have to have any distinctive Yamaha features, we still wanted to add something—however small—our competitors didn’t have. So we equipped the engine with a computer-controlled distributorless ignition system, added various new features, modernized it, and improved its reliability, user-friendliness, serviceability—all of which helped set our product apart from the competition’s.

To also make our drive unit stand out from the competition, we added trim adjustability, made it more reliable and easier to operate among other things. We also limited our unit to a single spec so that making changes to the internal gearing allowed it cover the entire model line, and offered counter-rotating propeller versions for boats with dual engine rigs.

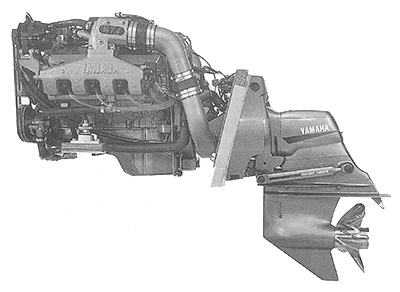

Since we were going to use GM’s base engines for the time being, they would be marinized in the U.S. so we had inboard manufacturer Crusader handle this to streamline distribution, improve our overall export profitability and speed up development.

This also helped to ease trade friction. Crusader has a long history and extensive experience as a manufacturer of inboard engines for leisure boats, and has a 45% share of the U.S. market. Our strategy was to have the completed engines marinized by Crusader and the completed stern drives built by Sanshin Industries be both mated and marketed in the U.S.

Although the engines would be manufactured in the U.S., the marinizing process and the drive units themselves all had to be designed by Sanshin. Making sure everything cleared standards and was satisfactory on both sides of the Pacific was a difficult process. We also made a company-wide effort to get production preparations, outsourcing of parts and more completed in time.

Then at the New York National Boat Show in January 1988, we debuted the 1989 model Yamaha stern drives and announced they would be launched for the U.S. and international markets. Thanks to everybody’s hard work, we had somehow managed to meet the demands YMUS had put forward.

An article for Yamaha dealers in 1988 covering the launch of our stern drives put on by YMUS for the American boating press

27Weather the Recession and Create Pioneering Products

Ironically, the U.S. boating industry boom that had continued since 1983 peaked in 1989 and began its downward trend. The rapid acquisition of boatbuilders and the increases in production to meet the growing demand of the industry’s boom years resulted in excessive product inventory. This further deepened the recession and sent the U.S. boating industry into the long period of stagnation we have today.

So the product we created with an eye to the future ended up being launched at the wrong time. We didn’t even come close to achieving our initial sales targets and because we invested such a huge sum for stern drive production, we have yet to amortize those expenses to this day.

World markets fluctuate constantly between good times and bad, but we cannot allow economic trends to heavily influence how we create our products. Even if it means a product’s launch will be slightly behind, we still need to build products with unique features that we can proud of and base them on clear long-term goals we’ve set, not rushing but working at a steady pace according to plan. It is truly saddening to see a company cave to the pressures of a recession and produce products lacking something different and only on par with the competition.

Following this, we began Step 2, the development of a big, high-horsepower stern drive. Since the only engine we could use for a large stern drive was a GM engine, we wanted to at least incorporate distinctive features into the stern drive itself. We equipped our unit with a hydraulic clutch—something no other company had done—and it eliminated the unpleasant shudder and clanking sound of gear engagement while delivering smooth shifts.

The YE-7.4L stern drive employed a Yamaha-exclusive hydraulic clutch design that eliminated the unpleasant sound and shudder of gear shifts, a common shortcoming of competing models.

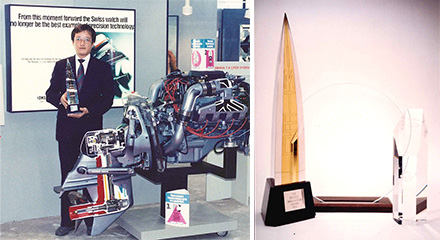

The cost of our stern drive is slightly higher but it is far more user friendly than competing units. In fact, it won the coveted Innovation Award at IMTEC in 1992, an honor bestowed to the marine product featuring the best technology in the U.S. marine industry for the year. It also won the Design & Engineering Award from Popular Mechanics, Best of Boating honors from Boating, and the Design Award METS at the Marine Equipment Trade Show (METS).

Yamaha’s hydraulic clutch stern drive design won numerous awards when it was launched.

This Yamaha stern drive has received rave reviews and is well-liked by users. From here, we must follow up with more improvements to our stern drives and reach our final goal of also offering customers engines with distinctive features. I’m sure the market won’t be satisfied with these heavy and dated GM engines forever, so our next task is to stay ahead of the competition and build a new, lighter and more compact stern drive engine. As our stern drives become a key part of our business, I believe they will become a product supporting the future of Yamaha marine engines.

28Afterword

Most of my life as a salaryman was spent as an engineer working on creating new products, so naturally the fondest memories I have are of building things. Today, Japan is said to have the most advanced product manufacturing technologies in the world. But back when that wasn’t the case—after the war when we had nothing—we worked wholeheartedly to catch up to the rest of the world quickly as we could, passionately dedicating ourselves to our craft. In that sense, I sometimes feel that the engineers of my generation were actually more fortunate with our lifetime experiences than engineers of today.

There are precious few things more wonderful than having an everlasting passion for your life’s work.

It’s when your job is a creative one filled with dreams that it no longer feels like a job, and one works with such zeal that time flies and the days become a blur. From the colleagues I hit it off with at Mitsubishi and spent my younger days with, my fellow Seven Samurai of Yamaha’s motorcycle beginnings, and the young engineers of the Yasukawa Research Lab, to the engineers we worked with from companies beyond our fences like Toyota, and my comrades from those early days when Yamaha outboards were still called songaiki (loss machines), it’s thanks to all of them that my life as an engineer was possible. However much time passes, their friendship remains the source of treasured memories I’ll never forget and my heart is filled with thanks.

Me and my colleagues at the time went to Florida to celebrate the tenth year of Yamaha outboards in the U.S.

No other job offers such tangible rewards as that of creating things.

Creations are honest; they do not lie. In that sense, interacting with these creations is wholly rewarding. In the free time that I have left, I will continue to strive for this honesty and to listen intently to my own feelings.

Now that I’ve finished writing, I realize that my more distant memories are fading and the entirety of my recollections may be unbalanced here and there. However, it can’t be helped as this was the reality of my life. Human memory has its flaws.

Whenever I found notes about something that had happened, I could recall the many other things that went on around that time, but otherwise, I’m afraid I’ve forgotten all but the most memorable occurrences. One should write down the biggest and most important turning points of one’s life, but one never really realizes how important they are when they happen. Only afterwards does one understand that, “Ah, that was an important time.” But by then it is too late; time has passed and what is needed is no longer there. Perhaps only those who were on the spot can really know how serious each moment was.

These fragmentary recollections of my experiences would be so much more complete if proper records remained from that time. That they don’t is regrettable. After all, there is no replay button to re-live your youth or your life.

In closing, for their assistance in the compilation of this book, I would like to thank Tomiyasu Oda, managing director of Oda Kogei Co. and Toshihiko Nishijima, editor of the Sanshin Industries company newsletter.

Chikara Yasukawa

May 1993

The author going for a ride in an outboard-powered race boat at a powerboat racing course in Miami.