What the Japanese Bayberry Trees Have Seen Stories from the Early Years of Yamaha Motor

1Introduction

Japanese Bayberry in front of the Hamakita Factory today (as of 1978)

Japanese Bayberry in front of the Hamakita Factory today (as of 1978)In the fall of 1954, the area around Nippon Gakki’s Hamana Factory—the site of Yamaha Motor Company’s present Hamakita Factory in Shizuoka Prefecture—was turning into a veritable beehive of activity.

Although the two wooden barracks-like factory buildings were surrounded by long weeds, giving them a rather forlorn appearance, on each side of the buildings were neat rows of ten-odd Japanese Bayberry trees.

Some twenty years later, though the trees had been moved and replanted elsewhere, they were more majestic than ever. Over the intervening years, the trees had been witnesses to Yamaha history and the comings and goings of people, but they can’t tell stories of what they’ve seen. If I may be forgiven for talking about myself, over the past few years, I’ve been given opportunities to describe my experiences as a Yamaha Motor employee, and many people have asked me to write about the company’s early years in the monthly newsletter. I was actually quite surprised at the number of people wanting to read about what things were like.

So, thinking that some might find it interesting, I decided to put down some of the behind-the-scenes stories from the early years of Yamaha Motor Company whenever I could recall them.

I realize that many will dismiss these stories as the idle ramblings of an old man, but as someone who was there from the very beginning, I feel it is my duty—so I tell myself—to put some of those recollections into some possibly biased words.

2Musical Instruments and Propellers

The author standing at a propeller display stand

The author standing at a propeller display standMost people know that Yamaha Motor Company’s origins lie with producing aircraft propellers, but few are aware of the relationship between musical instruments and propellers, so let me start from there.

It was on a chilly February day in 1935, a time when the economy started going downhill and jobs became hard to come by. I walked through the gate at Nippon Gakki for the first time and I was astonished to learn that the company was not only making musical instruments, but propellers as well!

In those days, most airplane propellers were made of wood. The hub and blades were made in a one-piece construction and they had a fixed pitch. Mahogany or walnut wood of the highest quality was selected and then artificially dried, after which it was carefully sawn into 20 mm thick strips, which were then glued and pressed together in layers and left to dry.

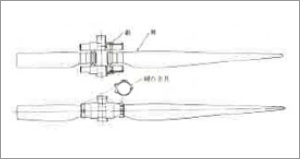

Manufacturing process for wooden propellers

Manufacturing process for wooden propellersThe result is a complex cross-sectional shape that is then shaved to create the propeller. The piece is then carefully balanced so that it’s symmetrical about its hub, the part attached to the engine’s crankshaft. This work can only be performed by master craftsmen in woodworking and it was amazing to see.

The finished propeller is then coated in urushi lacquer and ready to use. These precision woodworking techniques are very similar to those used in the manufacture of pianos, so it made plenty of sense that Nippon Gakki would produce wooden propellers.

3Metal Propellers

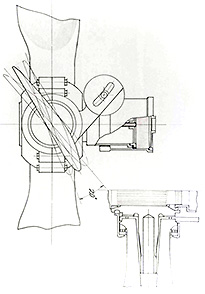

Construction of metal propeller

Construction of metal propellerOnce the manufacturing technologies for propeller production were firmly established, orders from the military inevitably increased. In 1931, the year the Manchurian Incident began, the manufacture of metal propellers also began.

The year after the establishment of Manchukuo and the May 15 incident of 1932, the methods for finishing the wooden propeller blades changed; they were sheathed in brass, the gaps were filled with celluloid, and the surfaces were carefully smoothed. These encapsulated wooden propellers developed by Nippon Gakki were both lightweight and very strong.

Then, on February 26, 1936, a day when the Hamamatsu area in Shizuoka was white with snow, the 2-26 Incident took place in Tokyo. In July the following year, war broke out with China and as the conflict pushed Japan further towards wartime production, preference for metal propellers increased.

In 1938, the propeller factory at Nippon Gakki was placed under army control. Day by day, employees originally building musical instruments were transferred to the propeller factory as propeller-related production became more crucial. Their work was deemed so important that workers at the propeller factory were given special badges with a propeller insignia; those without badges were forbidden entry.

4Hamilton Variable-Pitch Propellers

Hamilton Variable-Pitch Propellers

Hamilton Variable-Pitch PropellersWhile Nippon Gakki was making propellers for the army, Sumitomo Metal Industries was making them for the navy. However, Sumitomo had purchased production rights from American company Hamilton Standard for production of the Hamilton variable-pitch propeller, and they apparently began prototype production in 1937. Nippon Gakki also acquired the license to produce Hamilton variable-pitch propellers and began preparing to build them for the army in 1938.

Around the same time, new, three- and four-story concrete buildings were constructed at the main factory. Located on the east side of the main road was the so-called “new factory.” It occupied an area of about 13,200 m2 and had to be built in two stages. One after another, manufacturing machinery from Japan’s top makers was brought in and installed, as were machines from leading American companies like Cincinnati, Milwaukee, Heald and Norton, transforming the company into a major military production facility.

The engineering staff was tasked with translating the propeller and jig/tool blueprints supplied by Hamilton into Japanese. However, since each large blueprint from America contained drawings for many small parts and all the dimensions were in inches, a separate blueprint was needed for each part, all the figures had to be laboriously converted into millimeters, and the words themselves translated. I was in charge of planning and taking orders for the project and I can assure you that this was an enormous amount of work. At the time we had few machine tool specialists we could entrust this task to, so I’m fairly sure management also had their share of headaches!

5Propeller Production

According to documents, 1,584 propellers were produced in Japan during 1937. That figure rose to 1,846 in 1938 and to 4,033 in 1939, of which 1,466 were produced by Sumitomo and 2,567 by Nippon Gakki, about 60% of the total. Looking at the production capacity requirements from the military from 1939, you can see the breakdown of propellers produced at the time.

Propeller Production Capacity Requirements

Propeller Production Capacity Requirements(Approximately 2/3 of the fixed and variable-pitch metal propellers were 3-bladed.)

Thereafter, requirements from the military for production capacity increased significantly. During the first half of the year in 1939, average monthly production was approximately 320 props, and we were expected to nearly triple production by September 1941. For 1942, the national production goal was 12,522 propellers, but the figures for the later years of the war are unclear. However, monthly production was around 1,300 during 1944.

Most of these props were 3-bladed Hamilton units used on the Ki-48 twin-engine light bomber, with use spreading to the Ki-51 single-engine light bomber and the Ki-57 twin-engine transport. By this time, very few fixed-pitch metal propellers were being produced.

The factory was operating day and night shifts to meet demands and students, volunteers, draftees and others could be found working at the factory. There were as many as 10,000 workers at the time, and despite the ever-increasing likelihood of air raids, production continued with an emphasis on sending as many planes as possible to the warfront.

6Propeller Improvements

Towards the end of the war, plans were made to improve the Hamilton variable-pitch props. Also called constant-speed props, the benefit of the design was that it automatically adjusts the blades to their most efficient pitch angle while maintaining a constant engine rpm, thus allowing the most effective use of the engine’s power. These plans were put in place to meet the requirements for boosting overall aircraft performance.

In planning to improve the constant-speed prop, Sumitomo Metal had purchased the production license from Germany’s VDM, Nippon Gakki acquired the rights from Germany’s Junkers, and Nippon Kokusai Koku Kogyo (Japan International Air Industries) bought the rights from France’s Ratier-Figeac. The improvements were as follows:

In addition, Nippon Gakki was also planning to produce a special propeller which I like to call the “phantom propeller.”