Days Gone By Stories from the Trailblazing Years of Yamaha Motor

Introducing the stories behind Yamaha Motor's technologies.

5 Setbacks & Comebacks

So with this and similar failures, the Yasukawa Research Lab was disbanded in February 1962 and absorbed into the company’s engine department. Thereafter, the only project on which work continued focused on creating an improved version of the Tice Engine. In the end, the two sports cars our bold dream led us to build and the improved-but-unfinished Tice Engine were all that remained—an all the more sad conclusion to what we had started.

In November of that year, the two-pronged setback of a scooter model that flopped and a contraction in the motorcycle market forced Yamaha Motor to downsize, resulting in the Yamaha Technological Research Institute also closing. With the situation dire, many felt that the company just didn’t have the leeway anymore to continue work on car-related projects. We’d done so much and worked so hard to get started in the automotive industry, and it would be such a disappointment for everything to end like this.

So, I made a personal request to President Kawakami to allow us to continue our work. The president also wanted to somehow keep our aspirations alive, so company management went through the banks to see if one of Japan’s carmakers was interested in using our technology. It was likely thanks to the talks with the banks that one carmaker sent the head of their technology arm and other executives to visit Yamaha to see the cars and engines we’d built.

Seeing what we’d built in person is what likely convinced them, and we began drawing up the contract and specifics for a business partnership. A development department to specifically serve as the point of contact for work based on the partnership was set up at Yamaha. Executive Officer Ono was general manager and I was the department manager. Much of the team was made up of former members of the Yasukawa Research Lab that had been reassigned to work with us. We had been able to save our work on automobiles and secure its future.

The first jobs we worked on included designing a V8 engine, designing a prototype convertible top, and testing to see if installing our 2,000cc DOHC YX-80 engine—the improved version of the Tice Engine—could result in new models gaining a different character. In other words, most of the work we did was early-stage development.

6A Sports Car Known to Few

While working on these projects, our personal relationships with that carmaker grew closer and more frequent, and as we consistently built more and more parts and prototypes, they began to recognize Yamaha’s technological expertise. Then, it came—a full-on joint development project to create a new sports car from the ground up. We were ecstatic; we had finally returned to building sports cars!

The specifications for the car were as follows:

It would be powered by the 2,000cc, DOHC Yamaha YX-80 engine and use the chassis from an existing sports car, but with the suspension redesigned for improved high-speed driving. The styling would be handled by a designer from Europe working for the carmaker on commission at the time. His avant-garde design included pop-up headlights, a first for a car from Japan.

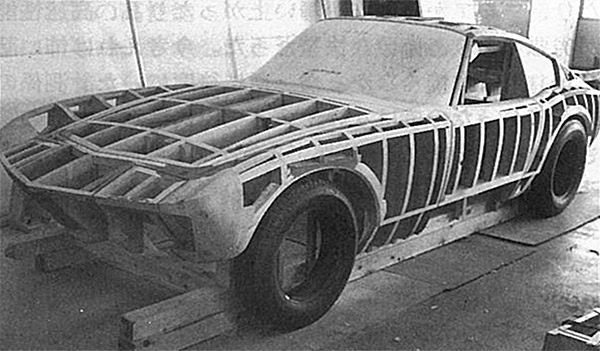

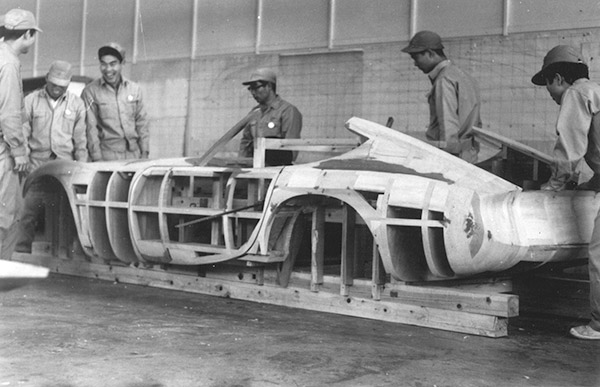

A wood buck of the mythical sports car’s monocoque body

While the carmaker handled the overall layout, Yamaha worked out the details of the design based on it and built the prototypes. Because the overall layout was well thought out and nearly finalized—and the fact that we used some existing parts—the prototype car was complete only ten months after we began working on the details of the design. This prototype was to be the automaker’s first true sports car and it was scheduled to be unveiled at the Tokyo Motor Show. However, issues arose and it was postponed indefinitely, never seeing the eyes of the public.

And so, aside from those of us involved with the project, I doubt many people even knew this sports car ever existed. After less than two years, our business partnership came to an end.

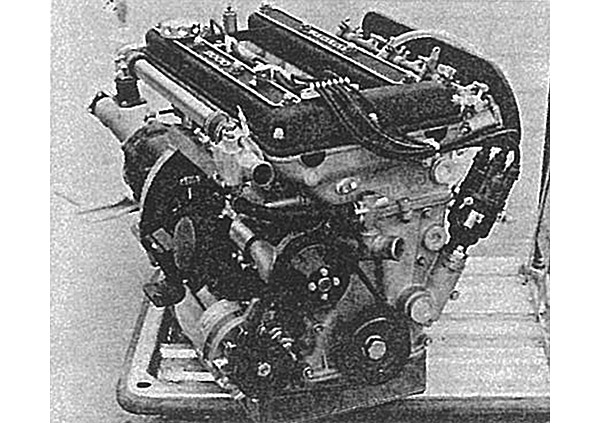

The prototype car we co-developed used the 2-liter DOHC YX-80 engine we created by making improvements to the Tice Engine.

The author (left) giving an explanation of the prototype to President Genichi Kawakami

7 A Request from Toyota Motor

Shortly after our previous business partnership ended, President Kawakami began to approach Toyota Motor. The first step was for management of both companies to meet. Vice President Eiji Toyoda (at the time), Managing Executive Officer Shoichiro Toyoda (at the time) and a number of other Toyota executives visited Yamaha and met for discussions with President Kawakami at Seifuso, the company’s private inn for visiting dignitaries. I was also asked to attend and explain the content and details of the car-related work we had done up to that point. I can still clearly remember how nervous I was.

Toyota likely wanted to ascertain whether or not Yamaha could really handle future automobile development work—some of which would involve handling confidential information—and there was also our business partnership history to consider. I have no doubt that Toyota visiting us that day was more of a preliminary investigation into what level of relationship they could have with Yamaha.

Toyota later asked President Kawakami to visit, so he, Managing Executive Officer Naka, Executive Officer Ono and I traveled to Toyota’s headquarters. Vice President Toyoda, Managing Director Saito, Managing Executive Officer Toyoda and Executive Officer Inagawa were waiting for us when we arrived. It was at this occasion that Toyota officially expressed interest in having Yamaha Motor work for them.

The outline of their request was to tune their existing engines for higher performance, assist in developing sports cars and related technologies, and carry out small-scale production as it entailed. More specifically:

The performance tuning was primarily converting existing Toyota engines to a DOHC layout, because they wanted to offer both OHC and DOHC versions for each of their engines. Their goal for DOHC engines was to use them in GT cars, and the first engine they wanted us to get to work on tuning was the 1,500cc 2R. We were even given permission to bore out the engine to 1,600cc if need be.

For the sports car job, Toyota was in the middle of planning a 2-liter sports car and they wanted us to manage the building of the prototype. The image for that sports car was similar to the cars Yamaha had built before, but we knew it was a task that would require some time.

When it finally came time to draw up the contract and other paperwork, both parties wanted to carefully go over everything while composing the agreement because this was the first time for Toyota to ever sub-contract this kind of work. Overseeing the relationship for Toyota was Executive Officer Inagawa, while Managing Executive Officer Naka oversaw things on the Yamaha side.

And this was how the foundations were laid for joint projects between Toyota and Yamaha Motor. It was back in November 1964. I could finally breathe a huge sigh of relief. Toyota probably couldn’t devote enough manpower at the time to handle early-stage development entirely in-house and they just happened to be planning to develop a sports car—we were in luck!

8Aiming for the Tokyo Motor Show

Once the management of both companies reached agreement, work quickly got underway. Five days later, Executive Officer Inagawa and Nakajima-san, the head of Toyota’s engine design department, came to Yamaha and we began discussions for the project to bore out the 1,500cc 2R and 1,900cc 3R engines and convert them to DOHC. The pace with which things moved forward was rapid; we were having meetings with Toyota every week. The engines we’d tuned were used in domestic racing to verify their performance and get results to show for our efforts.

As if setting up for our “second lap” with Toyota, by the end of the year we had been approached about building a 2-liter sports car. Talk about moving quickly from one thing to the next!

Toyota was already in the middle of laying out the 2000GT—a true sports car—in the product planning room under the direction of Project Leader Jiro Kawano. Because the entire layout of the car was expected to be finished around springtime, Yamaha was asked to do everything from the subsequent detail engineering work to building the prototype.

Toyota wanted to display the car at the Tokyo Motor Show set for the autumn of 1965, so we only had about eight months to complete the project if we were to meet the goal—this wasn’t going to be easy by any means.

From then on we had meetings with Toyota every other day. Unlike tuning the engines alone, building a complete car would normally mean putting together a large team that included all of the Toyota technical divisions involved, but going that route that would severely hamper progress.

Toyota affirmed that the project was a special case and made the somewhat unconventional decision to—in principle—not use its corporate management structure in the project to solve this problem.

So, Kawano-san (head of the project), Shinichi Yamazaki (in charge of the chassis and suspension), Satoru Nozaki (design & body) and Hidemasa Takagi (interior) from Toyota’s product planning team and Yamaha’s technical division would handle the sports car project. As a result, these four men were temporarily stationed at Yamaha and every day after that, we would all work well past clock-out time.

The fundamental concept for the project was to create a true, world-class sports car the likes of which had never been built before in Japan, so we tried to include any and all new technologies we could at the time. To power the car, we would build a new DOHC engine using the block of Toyota’s M family of 2,000cc straight-six engines, and use three two-barrel Weber40 carburetors. For the suspension, we chose 4-wheel independent suspension with disc brakes all around and magnesium wheels.

By altering the Toyota Crown’s engine to use a DOHC format, the Toyota 2000GT’s engine made much more power

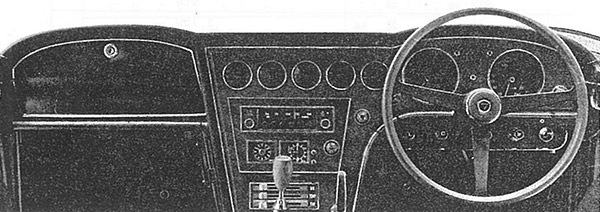

For the frame, we would use an X-shaped steel backbone frame made of thin-walled, large-cross-section tubing. The body was a semi-monocoque construction, complete with pop-up headlights. The steering wheel was to be handmade with several thin layers of high-quality wood and the shifter knob would also be wooden. The instrument panel was made of the same quality wood for pianos and given a painted finish in the same way. We chose cone-shaped, non-reflective plastic glass for all of the dials and gauges. For the hood and trunk lid, we used molded FRP pieces while the other body panels were to be made of hand-formed steel sheet. The Keihin area of Tokyo and Yokohama was the Mecca of sheet metalworking at the time, so we hired the very best craftsmen from there for an exorbitant amount of money to do the work for us.

The Toyota 2000GT’s interior took advantage of wood’s quality look and feel, employing the mahogany and painting techniques used for Yamaha pianos. The steering wheel and gearshift knob were also made of wood.

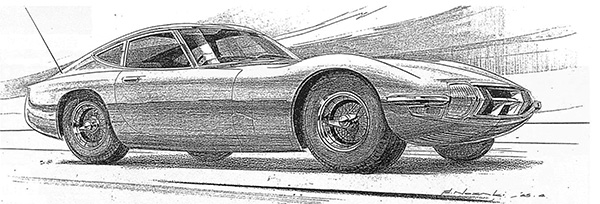

For the exterior design, Nozaki-san drew up a ½-scale dimensional outline sketch based on a stockpile of grand tourer concepts he’d come up with while studying at the Art Center College of Design in the U.S. He then he photographed the sketch and enlarged it to full-scale. From there, the sketch was transformed into a wooden body buck and used to check the styling and contours for the metal body panels as they were being built.

This was the markedly simple design method we had for the project, employing neither lettering nor even a clay model in the process and only using a few memo-like sketches and outline drawings. For the detail engineering work as well, we prepared everything with memos and sketches. The end result was the unprecedented speed with which everything moved forward.

One of the sketches done by the car’s designer, Nozaki-san, in April 1965 for presentations. It was based on the car’s outline drawings, which had been created earlier in the car’s development.

There was less than eight months’ time to build the car in time to unveil it at the 1965 Tokyo Motor Show. The wooden body buck for shaping the body panels was built based on ½-scale dimensional outline sketches, and the team checked the car’s styling as they worked to create and finalize its form and shape.