Yamaha Journey vol.29

Metabon’s touring adventure of Eurasia and Africa on a Yamaha XT660Z Ténéré.

A miracle encounter beyond the horizon.

Metabon

XT660Z Ténéré

#03 Africa: Heading south, chasing the summer

Africa Part 1 in 2019

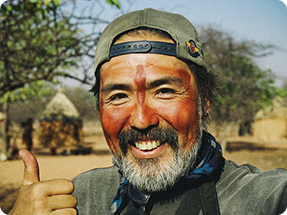

Koji Mochizuki (Metabon) was born in Tokyo in the first half of the 1970s into what is often called the lost generation. Metabon had an adventurous streak, which led him to take to the road to make a continuous journey across the Eurasian and African continents. In this installment, Metabon faces the challenges of rough roads and unreliable information while taking in the great outdoors as he heads south across the vastness of Africa on his trusty Ténéré.

If you look closely, you can see that the blue walls have several different layers of paint, which gives an interesting depth to them.

Chefchaouen looks magical in the moonlight.

Chefchaouen, Morocco

The sight of this stranded shipwreck particularly struck me.

I started imagining what could have happened to the passengers on board, and I wished I could explore.

El Marsa, Western Sahara

These uniquely decorated fishing boats are a labor of love. I was surprised to see the Japanese flag being flown on one boat.

It made me feel a connection between Ghana and Japan.

Elmina, Ghana

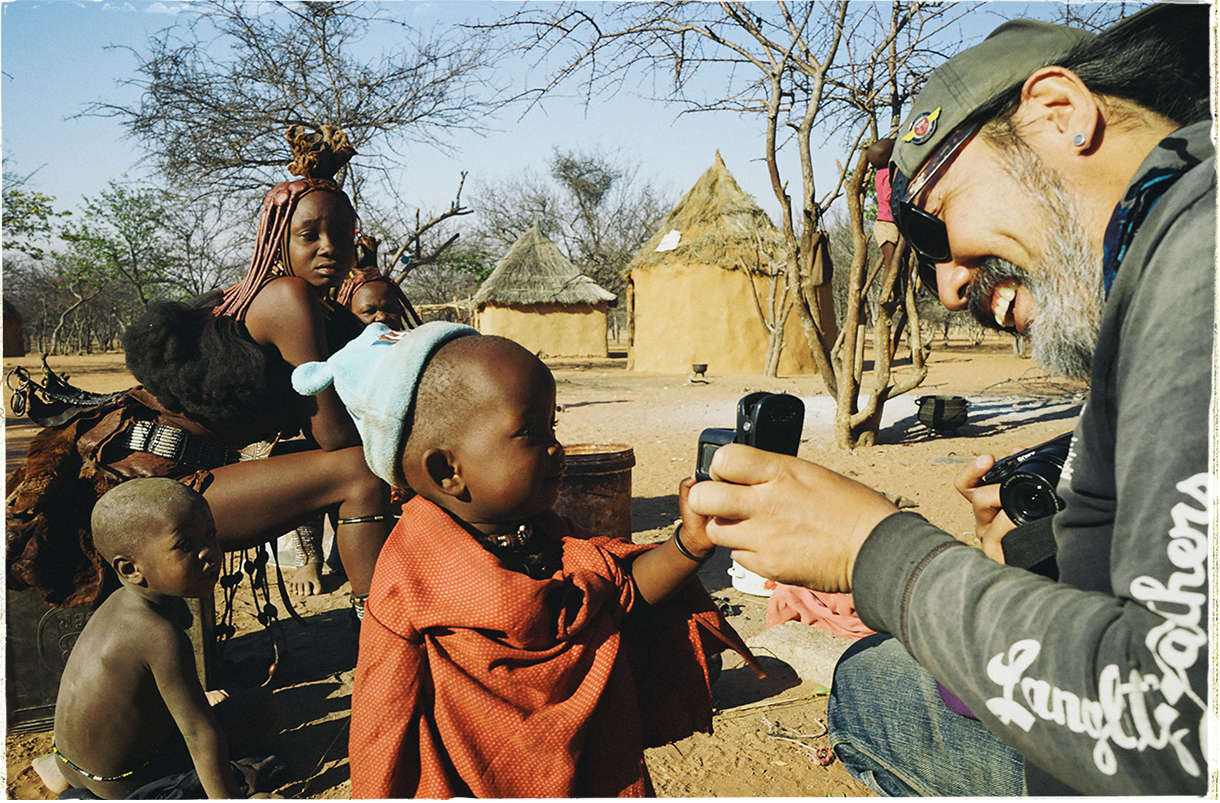

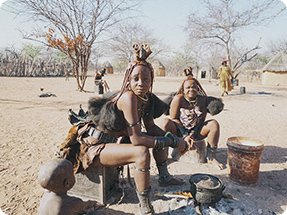

We had an unforgettable time with the Himba people. This child mimicked me saying “kawaii”, which means “cute” in Japanese.

Himba Village, Namibia

The blue city of Chefchaouen, the gateway to Africa

I had been searching for information prior to the Africa leg of my journey, but with my poor English, I was pretty concerned that I hadn’t found what I needed. You can find info on your smartphone about border crossings, how much a visa costs, places where you can camp, and so on, but in some countries information isn’t as readily available, or you never know when things might change – and it’s often impossible to even exchange money.

I boarded the ferry from Tarifa in Spain to Tangier in Morocco with a fair bit of anxiety about the coming leg of my journey. Getting off the boat into a new continent was much easier than I expected — the officials checked if I had a gun or a drone on me and then stamped my passport.

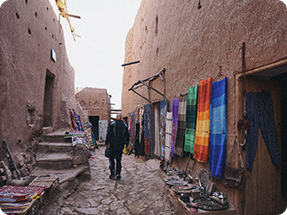

After a short break in Tangier, I headed towards Chefchaouen, and by the time I arrived there, it was already dark. Even at night, I could understand why Chefchaouen is known as the “Blue Pearl of Morocco”. The town is one of the prettiest in Morocco due to its blue-washed alleyways and buildings all painted in different shades of blue — from periwinkle to picotee —giving it a fairytale-like quality.

The next morning, when I stepped outside from the hotel, I really got a sense of just how blue the town was. Through the heaving hustle and bustle of tourists taking selfies, I felt a different kind of magic from what I had experienced when I arrived at night. Despite the crowds, the town still gives you the feeling you are on a movie set, albeit one with lots of stray cats. In addition to tourism, fishing is also a major industry here.

That evening, I received a message from my friend Takeyan, who I had met in Spain. He said he wanted to meet up with me again and asked if I could come and join him soon in Marrakech, where he was staying. I decided to cut my time in Chefchaouen short in order to continue my journey, and I headed on to Marrakech.

Marrakech is an old town, and the streets are so narrow that it’s quite difficult to get around on a motorbike. At one point, a group of young boys approached me and said if I gave them some money, they could guide me to a parking lot. I was later told that I was in an unsafe area, so it is best to be on your guard at all times.

At the cheap hotel I was staying at, it was about 50 cents for an all-you-can-eat breakfast, so I filled up on mashed potato and pita bread with lots of olive oil.

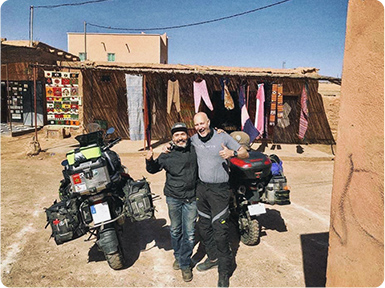

On the road from Morocco to Western Sahara, I made friends with a German man called Mathis, and I decided to ride together with him to Dakhla. On the way there, we found the ruins of a petrol station with a sign saying Gas Haven. At first, we thought it was just another abandoned building like some of the others we had passed, but this one was more striking, and it turned out to be part of the set for a horror movie called The Hills Have Eyes.

I found the language barrier harder in Africa than I had in Europe, and I came across some other difficulties. Even the price of water in the same shop can vary from day to day, and any information I got would be different from person to person.

I also found the accommodation situation in Africa pretty challenging. Sometimes the only way to find a hotel is to use a certain smartphone app, and rooms aren’t often available when turning up without a reservation. Namibia is a paradise for camping, but in many other African countries, the wildlife is so dangerous that it makes sleeping outdoors impossible.

After I left Morocco, I felt that the journey had just begun, and with a more anxious disposition, I drove the Ténéré towards Western Sahara.

The Mauritanian border – like something out of a movie

After driving through the wilderness of Western Sahara, Mathis and I suddenly arrived at the coast and were greeted by a deserted shipwreck stranded on some rocks a little way off the beach. The Canary Islands were a short distance away from where we were headed, and our surroundings gradually got more luxurious as we followed the coastline. We had reached Dakhla, a resort town popular for marine sports. We stopped to take in the beautiful sea and the sight of holiday-makers enjoying sunbathing and parasailing.

Outside of the tourist attraction of Dakhla, I got the impression that there was nothing but desert in Western Sahara. After parting ways with Mathis, I pressed on across the dunes until I reached a small oasis town where I found a hotel to stay the night. There was a gas station adjacent to the hotel, so I thought it was the perfect place to stay. There was netting between me and the vaulted ceiling in the hotel room, and birds and dragonflies were coming and going on the other side of it throughout the night. Before I left in the morning, I filled up the Ténéré’s tank. In Africa “gasoline” is sometimes referred to by different names— and as engine trouble can be fatal, I learned to be cautious and smell any fuel before putting it into the bike.

In Africa, borders are often vague. As a result, the area around the border between Western Sahara and Mauritania has an unsettling atmosphere, with armed military guards, abandoned vehicles, and even landmines. With its desolate environment, it reminded me of apocalyptic scenes from movies I had watched. I heard an interesting story about a French engineer who almost got lost in the desert because his car broke down, but he converted it into a motorbike and managed to get home.

In Mauritania, due to the currency exchange, I often found money to be a problem, and I was charged $300 for a shabby hotel room. Furthermore, there are no addresses in the desert, so I had to rely on smartphone apps to find the hotels, only to find that they had disappeared when I arrived at the destination.

On the way to one hotel, I saw a burnt-out car that looked like a zombie with its headlights dangling like eyeballs popped out of their sockets. I made the decision to just keep riding through Mauritania.

Guinea – a poor country but rich in spirit

I rode across the border into Senegal, where my friend Takeyan was waiting for me. We went out for a meal and had tiep, a staple dish from the region which reminded me of paella. It only cost $1 but was absolutely delicious. After an enjoyable evening catching up with Takeyan, I left Senegal for Guinea.

As I was entering a region where malaria is a big problem, I bought some insect spray that contained a lot of DEET, which works well to repel mosquitos. It was a bit pricey, but I was told it keeps biting insects away for longer than regular insect repellant.

The roads in Guinea are not very well maintained and are covered in powdery soil that is bright orange. For some reason, I couldn’t find much information about the country on the internet. Once I arrived, I found that the people were friendly and honest.

I moved on to Côte d'Ivoire and stopped off in Yamoussoukro, where I visited The Basilica of Our Lady of Peace, the largest Catholic cathedral in the world, admiring its overwhelmingly vast grounds and beautiful stained-glass windows.

I tried to get a visa to go into Ghana from Côte d'Ivoire, but my application was rejected. I spent two weeks at the embassy, trying to look as clean and presentable as possible by changing into jeans instead of shorts, but the answer was a resounding "no". When I told them that I had no choice but to take a diversion through Burkina Faso, they said, "It's dangerous there, that’s not a good idea,” and then issued me with a visa for Ghana. I couldn’t understand why they suddenly changed their minds.

The people of Ghana are very friendly to travelers from Japan, and I was surprised to even see fishing boats flying the Japanese flag. Abidjan, the former capital of Ghana, is known as the New York of West Africa. The locals explained to me that having a nice set of wheels is very much a status symbol here, and I could see many luxury cars on the road.

As it is related to my job in Japan, I have an interest in funeral customs in different countries. In Ghana, it is traditional to bury people in unique coffins that have a relationship to the deceased. For example, if someone was a pilot, they will be buried in an airplane-shaped coffin, and if they liked chili peppers, they would be buried in a chili-pepper-shaped coffin. You can see people making these brightly colored coffins on the streets. I’m told that funerals here have a cheerful atmosphere with a lot of singing and dancing, but I didn’t get the opportunity to experience one first-hand.

The plan was to travel south through Nigeria, but at the time, the country was in a very dangerous situation, and it was doubtful that we would be able to leave. So we decided to fly from Cotonou in Benin and take our bikes by boat to Libreville, the capital of Gabon.

My bike was lifted by a crane and treated like scrap metal, and when I got it back, the headlight had been smashed. I naturally pointed it out to the officials, but they just replied, “It’s OK. You can still ride it.”

It was the rainy season in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and I heard that the condition of the roads there was very bad. I had planned to wait in Libreville for the weather to improve before crossing the border, but after two weeks, the weather still hadn’t improved. However, my visa was running out, so I decided to pack my gear and set off to face the storms.

The next three days were hell on earth. It was raining so hard that I had no idea where the road was. The navigation app I was using was useless as it was off by 100km. Furthermore, I couldn't find a place to stay, so I had to run into a church I passed, and I asked to stay there. I was, of course, incredibly grateful for the accommodation, but the place was crawling with insects, and although I was absolutely exhausted, I spent a sleepless night there contemplating my life.

Malaria and the Himba people in Angola

I somehow managed to get to Pointe-Noire barely alive and traveled down to Cabinda, an exclave and province of Angola. A member of a motorbike club we met by chance helped us get into the country smoothly.

Just as I was getting on the plane and feeling relieved that I had made it out of the Congo, my health took a turn for the worse. I started to feel anxious, restless, and unable to think clearly. My body temperature dropped, and I started getting cold chills. I knew this was definitely more than just a cold. Luckily I had met up with Takeyan again, and he was riding with me at this time. He helped me get to a doctor where I was diagnosed with malaria, as I had feared.

Just when I thought the medicine was helping and I was feeling better, my condition deteriorated again, and I spent the following day doubled up with cramps. I started to get really worried about where I would be taken if I lost consciousness. It was unusual for me to completely lose my appetite, but I didn’t have the energy to even make a cup ramen, so I had to ask Takeyan if he could go out to buy me some food. After five days of doing nothing in the hotel, I finished the course of medication and was finally on the mend. There are different types of malaria, and I was lucky to have a milder variant known as the “three-day fever”.

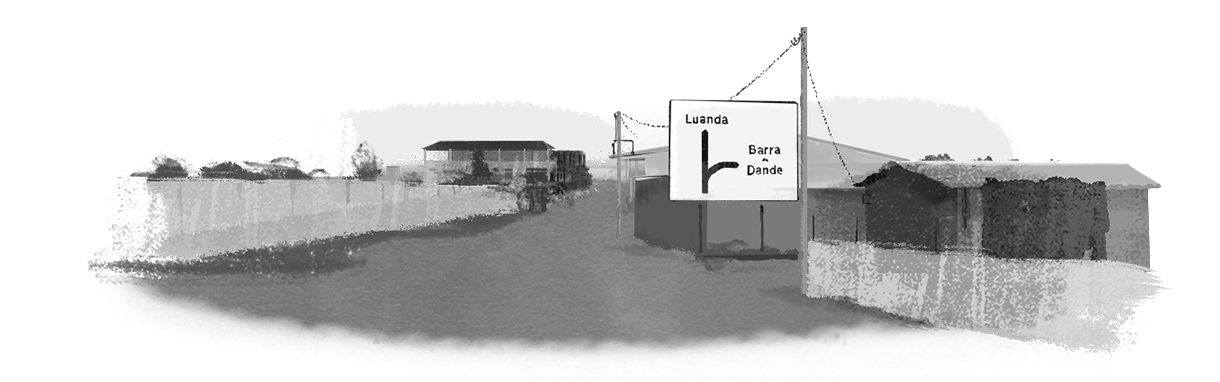

Now feeling better, I headed for Luanda, the capital of Angola. We pitched our tents next to what is known as the most expensive resort in the world, with a view of the luxury cruise ships docked in the port. The next morning, we stopped at a gas station to fill up before a busy day of touring. To our surprise, they were totally out of petrol. We waited there apprehensively for the tanker to arrive with what we needed.

After finally managing to refuel and touring for a bit, we came across a group of Himba people. They offered to have their picture taken with us in exchange for some money — something they often do when they see tourists. They smear butter and soil on their skin which is believed to help repel insects.

An interesting exchange in Namibia

On the way to Windhoek, the capital of Namibia, Takeyan wanted to photograph some animals in the desert, so we drove hundreds of kilometers to Sossusvlei, also known as the Red Desert. The contrast of the red earth and the brilliant blue sky providing a backdrop for the rows of salt-air-blasted leafless trees set a scene resembling a surrealist painting by Dali.

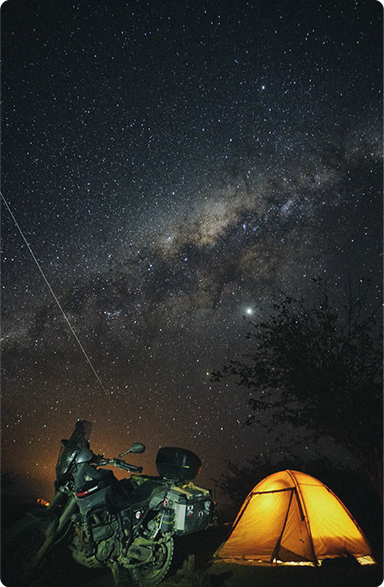

At the campsite, I also tried my hand at some photography. I wanted a shot of the night sky and the bikes, but it was a challenge to get it right using a camera I was unfamiliar with. After a lot of trial and error and messing about with the exposure and shutter speed, I was ready to take the shot, and just that very moment, a shooting star shot across the sky. It was incredible to capture that, and sheer luck that I was able to take such a perfect picture.

There are good supermarkets, comfortable hotels, and decent campsites in Namibia. However, we were not able to camp in the capital city Windhoek, so we found what we thought was a cheap hotel online. We had some disagreement with the hotel manager, who disputed the cost of a room we had seen posted online. “We’re not that cheap a place!” she asserted adamantly. The baths were also under construction, so the guests couldn’t use them. But there was nowhere else we could stay around there, so we reluctantly agreed to the price she quoted us.

Just as I was thinking that we’d been ripped off, the manager apologized for the baths being out of action, and she filled a large tub with water she had heated up in a kettle for us. Thanks to this, I felt refreshed and slept well that night.

I woke up to a hearty breakfast carefully laid out along with a letter of thanks. As I was getting ready to leave, thinking how nice this hotel actually was, I saw the manager looking hesitantly through the door. She then put a small amount of money in our hands and said, “Make sure you have some lunch.”

Sometimes people who seem disagreeable at first often turn out to be very hospitable. With that thought in my mind, I mounted the Ténéré and headed south.

Metabon (Koji Mochizuki)

Born in 1975 in Tokyo, Metabon loves biking, camps, and bonfires. Every day at work, he daydreamed about riding my Ténéré. On his days off, he spent time on his bike, using touring as escapism. Traveling further and further, he started to set his sights on going