What the Japanese Bayberry Trees Have Seen Stories from the Early Years of Yamaha Motor

28“Learn by doing!”

Once an arrow is shot, it cannot return. After creating and selling the first YA-1, we couldn’t rest on our laurels because we still had a lot more to build. Keeping bikes coming off the line came with some serious challenges, but we managed to finally complete six more machines by February 13th, 1955. Though our production process had been like a wheel stuck in the mud, it was slowly beginning to gain traction.

However, once full-scale production did start, that in itself became the cause of tremendous self-reflection within the company. We suddenly had the painful realization that in the ten years since the company last produced propellers, our metalworking techniques and technology had fallen far behind the times.

To rectify this problem, Manufacturing Division General Manager Aisa visited Hitachi Seiki’s Abiko Factory in Chiba Prefecture, which was said to have the latest machining technology and machinery. Amazed by what he saw there, he called a meeting upon his return about how to address our machining issues.

As a result of this meeting, Nippon Gakki’s Metalworks Department Manager Nakatani and myself were charged by the president to learn modern machining methods first-hand and to integrate them into our operations as soon as possible. I was worried about our motorcycle production since it had only just started, but we were ordered to set off for training immediately. So, on February 18th we left for what would be roughly a month of instruction.

In situations like this, the most experienced workers would typically be selected for training, but the president insisted the department managers overseeing the workplace should be the ones to experience these new technologies for themselves.

We went to Abiko in Chiba and rented rooms in an old inn. We began our temporary lives as workers on the factory floor and learned how to operate modern metalworking machine tools. Though we were managers at our own company, we were given no special treatment and we toiled hard and ended our days covered in grime and oil just like all the other workers.

Our first job was using a turret lathe to cut 70–80 mm thick steel. The same task at the Hamana Factory would mean using high-speed steel bits to slowly make the cut, and it was always a laborious process. But here, the tools made by Tungaloy and other brands that used superhard alloys would just generate some smoke as they cut through the steel like a hot knife through butter. We just stared, dumbfounded at how fast they made the job.

Our duties also included cleaning the machines, removing the chips and shavings, sharpening the tool bits and setting up the machines. The scoldings we received whenever we had to ask one of the old timers for help in changing tools was just part of the job.

In what little free time we had at work, we made notes about the various shapes of the tool bits and tool holders, work conditions like workpiece rpm, feed speed, depth of cut and all manner of other information. Then, every evening after returning to our rooms, we would use this data to write reports on our progress in the dim light of a low-wattage bulb and send the report off to our company. Everything we learned during the day was written down that night and sent off immediately.

Some of the reports from our time at Hitachi Seiki

We never missed a single day, and I think it was because we felt like pioneers discovering new worlds of technology for our company. Consequently, it wasn’t until around midnight that we were able to bathe and cleanse ourselves of the dirt and grime. So when I look at the few surviving reports today, they vividly bring to mind the stench of sweat and cutting oil which permeated our working days.

Based on the data we put into these daily reports to the Hamana Factory, new machining techniques and conditions were tested and those that proved effective were utilized immediately. Sometime during our third week, we were joined in our training by General Manager Takai and Technical Department Manager Nemoto. Watching them work, I saw how effective our own training and the reports we’d been sending back about the new machining technologies and techniques had been.

When we finally returned to our factory, even we were astonished at the dramatic improvement in machining speeds. It was a perfect example of our company’s motto pushing employees to be “Quick and astute in action.”

In any event, the knowledge we gained during the one month we’d spent learning by doing was of priceless value and I think it made a huge contribution to the operation of our factory. President Kawakami would later send us off for all kinds of other hands-on training. Each time, we returned grateful for all that we learned and thankful for his wise leadership.

29The Story of the Gears

In February, we somehow managed to assemble 30 motorcycles, 17 of which were shipped out. However, shortly after we returned from our training at Hitachi Seiki in late March, we ran into a big problem with the precision of our transmission gears. As production proceeded, it was only natural that our ears became more attuned to the sound of the engines and that quality control standards became stricter. The biggest problem we picked up thanks to this was the noise we’d hear from the gears.

At the time, we believed that the best way to produce high-precision gears was to lap the teeth in by running the two gears together simultaneously during the final stage of finishing. But since the gears were surface-hardened by carburizing after machining them, if we had gears with imprecise teeth cuts at first or warped teeth caused by the heat treatment, we couldn’t improve the precision of the gears by lapping.

The problem was the machinery we were using to cut the gear teeth: an old Reinecker hobbing machine from the propeller production era—even back then it was rarely used—that simply wasn’t good enough. Also, our skill at polishing the hobbing tool was inadequate and on top of that, our heat treatment capabilities were still lacking, so it was only to be expected that our gears would be so noisy.

In an effort to rectify the problem, we visited various companies specializing in gear making and got advice from experts, but none of it resulted in a quick fix to our problems. It wasn’t until May that we discovered our miracle-maker. At an international trade fair held in Tokyo, Manufacturing Division General Manager Aisa saw a Reishauer gear grinder on display and suggested we get one.

At the time, gear grinding could only be done with high-end tools and machinery, making it an inherently expensive process. However, the Reishauer method stood out in that it was particularly well suited for mass production. Technical Department Manager Nemoto immediately paid a visit to Ikegai Metalworks, which had already purchased such a machine and put it to use. They tested the machine with one of our gears for him and the grinding time per gear was 3 minutes and 18 seconds, convincing him of its suitability for mass production.

However, the machine’s astronomical price of 12 million yen was far beyond what the Hamana Factory alone could afford. Instead, on May 25th it was decided to purchase the machine and install it in Nippon Gakki’s machine tool factory. The first motorcycle gears produced by the Reishauer gear grinder were used in the bikes that would compete at the Fuji Ascent Race [mentioned in the next story].

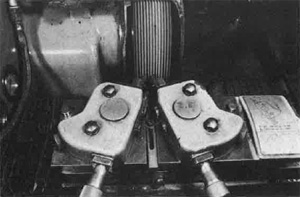

The Reishauer grinder in action shaping a part with a grindstone

The Reishauer grinder in action shaping a part with a grindstoneThis gear grinder was key in establishing Yamaha’s reputation for high quality, and the company has since installed 13 of these machines. Improvements in our gear machining technology have made it no longer necessary to grind the mating surfaces of every single gear, but I think that Reishauer gear grinder was a significant factor during the company’s early years. After all, it solved all our gear whine problems with a single stroke.

30Preparing for the Fuji Ascent Race

It was towards the end of May that the idea of entering the Fuji Ascent Race came up. Sponsored by Motor Magazine Ltd., the race’s chairman was the magazine’s president, Masafumi Kimura. I remember Shouichi Shiozawa, the head of the magazine’s Shizuoka office, working very hard to organize the event.

The 24.2 km course ran on public roads (a mountain trail, really) from the Sengen Shrine in the city of Fujinomiya to the 2nd station on the front side of Mt. Fuji. The 1955 race would be the third time the event was to be held. The previous two events were both won by Honda. If we would be participating, our main goal was high and pretty straightforward: beat Honda.

The first task was to begin building engines for racing, but we still had very little knowledge about how to increase an engine’s horsepower. Nevertheless, our engineering team rose to the challenge by trying all manner of tuning measures to build some racing engines and send them off to the team that was practicing at Fuji. By June 25th, 20 engines had been sent, followed later by 14 more.

It was around then that we received a report from Fuji that Honda had upped the performance of their 125cc machines by going from 3-speed transmissions to 4-speed ones. This was a source of much concern to the team’s support group. The Yamaha team consisted of ten riders. Pre-race testing and practice continued at a furious pace, but because the course was a one-way hill climb and not a looped circuit, the team could not measure their times.

President Kawakami suggested that we use radios. The team immediately set about devising a strategy to precisely—and secretly—record and relay times at the starting line, the 1st station and at the finish line. Of course, they also recorded the times of the competition, giving us a very clear picture of our own performance. Talk about a great idea!

Led by Technical Department Manager Nemoto, the engineers in the team support group back at the factory continued their attempts to boost the horsepower of the race engines, but it was proving to be far more difficult than we had imagined. It was at this juncture that a dove of good fortune came to the rescue.

31“Yamaha Motor Company”

The main gate at the time

The main gate at the time It was on July 1st, 1955 that Yamaha Motor Company became independent of Nippon Gakki. I remember that there was actually no huge hurrah or special ceremony held to commemorate the event; the change was simply the filing of the relevant documentation and legal recognition of the company.

We had 30 million yen in capital. President Kawakami was at the helm (in addition to his position as the head of Nippon Gakki), and Nippon Gakki Manufacturing Division General Manager Aisa was made Managing Executive Officer. The board of directors included Nippon Gakki Managing Executive Officer Ogura, Technical Department General Manager Takai and General Manager of Operations Kubono. Director Shunsaku Aisa and Tokyo Branch Manager Kamiya took on positions as auditors. Manufacturing would be handled by Yamaha Motor Company, but sales would go through Nippon Gakki. The total number of Yamaha Motor employees we had was already over 150.

Anyway, returning to the dove of good fortune which visited the engineers, it appeared in the form of the muffler fitted to the latest model of DKW. When the engineers attached this muffler to the YA-1 engine, they were astounded to see a gain of 0.5 horsepower. They had no idea that a muffler alone could so significantly change an engine’s output.

The tip of the muffler on the original YA-1 had a fishtail shape, so the engineers changed it to a simple round pipe. Back on Mt. Fuji, the race team was sweating blood in their non-stop training, looking to come up with any and all stratagems in their quest to defeat Honda. Hardly a day passed when the support team at the factory didn’t receive urgent requests for ever better engines.

With just a week left, the engineers began working day and night on the race engines. On July 6th, President Kawakami came by to personally direct the engine testing. As we tried numerous approaches over and over in an effort to improve intake efficiency, one of the most effective in upping horsepower was changing the carburetor’s needle jet. This discovery inspired the engineers to even greater efforts.

They finally ended up toiling through the night with President Kawakami at their side. The dynamometer needle would go up and then down, and pistons would seize, toying with our emotions—joy of what seemed like success soon making way for frustration and defeat. I was also there overseeing things with President Kawakami, and was witness to everybody’s faces and them swatting at the swarms of bloodthirsty tiger mosquitos attacking their sweat-drenched skin as they refused to give up. It’s a scene forever burned into my memory.

The day after our all-nighter, July 7th, Factory General Manager Aisa officially announced to everyone that Yamaha Motor had separated from Nippon Gakki and was now an independent company. For the senior staff of the Manufacturing Department, the new foremen were Ogai-san, Nagata-san, Aisa-san, Sagara-san, Suganuma-san, Atsumi-san, Kinoshita-san, Yamashita-san and Takeda-san. Of course, there was no head supervisor.

We had finally built 14 racebikes and shipped to the team at Mt. Fuji. That was an incredibly busy day and since we were still very low on staff back then, none of us had the time for rest or sleep. President Kawakami was there with us again and every member of the team once again burned the midnight oil.

We were later flabbergasted to hear news from Mt. Fuji that Honda had delivered their latest high-performance racing engine to the site by helicopter!

Also on the 8th, we shipped each of the 14 additional engines to the team on Mt. Fuji whenever we completed one. To allow the work to continue without interruption, the engineers catnapped in shifts during the day. The night of the 8th was their third all-nighter in a row. Finally, time was up. Five spare engines were loaded into the trunk of President Kawakami’s Ford and he and Department Manager Nemoto were driven to Mt. Fuji by Tamaki-san, the president’s personal driver.

They departed at 2:00 in the morning of the 9th, but the eastern sky had already begun to lighten; dawn comes early in summer. Now, only one question remained: would the Mt. Fuji Ascent Race foretell Yamaha’s future in the motorcycle industry?

After toiling virtually without rest for days on end, when we finally waved President Kawakami off from the lawn in front of the factory, we were so exhausted we could barely tell front from back. We were still sleeping on that very lawn when dawn came.