Days Gone By Stories from the Trailblazing Years of Yamaha Motor

1A Bolt from the Blue

In May 1971, I was suddenly summoned by Managing Director Koike. When I arrived at his office he simply said, “You and Ueshima are being recommended for promotion to executive officer. I want both of you to go see President Kawakami.” While I was initially overcome with emotion and became very tense, it all turned to astonishment when Koike-san said, “However, we won’t have you working on cars anymore; you will be directing our outboard motor operations as General Manager of the 3rd Engineering Division.”

I was completely taken aback. Thinking it would be my life’s work, I’d poured my heart and soul into the automotive work we were doing, and I’d enjoyed it immensely. By contrast, the company’s outboards were being bombarded with customer complaints and had such a poor reputation that instead of being called sengaiki (outboard motor), they were derisively called songaiki (loss machines). Of all Yamaha’s products, it had become commonly accepted that our outboards had the bleakest future. We were managing to export some models to Europe at the time, but Executive Officer Nagaoka—he was in charge there—flatly stated, “Our outboards are third-rate products no matter where you go, so you’ve got to at least make them second-rate ones.”

An article talking about Yamaha outboards in Europe in a newsletter issued in 1967 for dealers in Japan

Yamaha outboards were also being exported and sold in Europe.

At a boat shop in the Netherlands at the time

To be honest, while I was quite flattered to be promoted to an executive position, if it meant I had to be in charge of outboard motors, I felt like I’d rather quit. But after thinking it over for about a week, I realized that I’d been assigned the task because the higher-ups thought I was someone they felt they could entrust such a difficult job to. So I decided to do it, but I remember making a promise to myself: if I was going to do it, my duty would be to make Yamaha outboards among the best in the world. And that’s how my involvement with outboard motors began.

The first thing I did was go to the U.S. The market there was the most advanced and accounted for half the world’s outboard demand. If our outboards couldn’t gain a foothold in America, there was no way we could say they were of the highest quality. I thought that to really understand what outboards were and how they worked in people’s lives, I had to see the American market firsthand.

However, Executive Officer Nagaoka in Europe chastised me for this: “Since you’re in charge of outboards now, you should be going to Europe where we actually sell Yamaha outboards! Why in the world are you jetting off to America first thing when we don’t even sell them there?!” So my decision ended up offending the person actually responsible for marketing our outboards.

Following that incident, I worked to make up for it and visited Europe about four times annually for the next three or four years, making sure we communicated better about what we were working on. But even now, I still think that my decision to go to America before I had any biases about outboards and try to grasp an understanding of the market first was the correct one.

2Doing Good for Others Is Doing Good for Oneself

Thus began my work with outboard motors. Back then however, we were so overwhelmed with handling complaints with our products every day that we had no time to develop new models, and on top of that, we were also short of personnel. We were simply in no position to formulate any kind of business plan. At the time, I felt there were three tasks I had to accomplish:

1. Gather the right people and build a proper base of operations.

2. Solve the immediate problems causing customer complaints.

3. Develop new models.

I got started by gathering the right personnel. At the time, the 3rd Engineering Division (Outboard Motor Engineering Division) consisted of 18 people doing design and testing, but only about 10 of them were engineers so things were wholly inadequate to get work done properly.

“We have to make a serious effort to grow our outboard motor operations,” stated Managing Director Koike at an executive officer board meeting. “To do that, we need to boost the number of personnel in the 3rd Engineering Division, so I want to reassign some people from the 1st Engineering Division (motorcycles) and the 2nd Engineering Division (snowmobiles).” This motion was passed by the board.

But while they all agreed that the idea was good, nobody was willing to make the sacrifices necessary for it. So once more concrete meetings began to reassign people, not a single candidate emerged. This is a common problem where personnel matters are concerned. For the time being, I hoped to secure reinforcements through regular in-company rotations and used every card in my hand to negotiate some transfers, but the effort proved futile. So in the end, I had no other alternative but to take a chance and hire some new people from outside the company.

Every single day for the next six months, I trooped over to the human resources department to search for suitable applicants and made sure I was present at the job interviews. For quite a while, doing all that was the most urgent part of my job. All of the mid-career hires were assigned to the 3rd Engineering Division, and I also did whatever I could to get as many new hires assigned there as well. People ended up calling me “Yasukawa the Kidnapper,” but I was in dire straits.

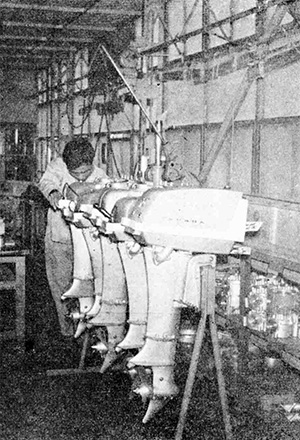

The outboard motor assembly line at the time

I remember when I was still in charge of the automotive engineering division, I was told that the outboard business was having trouble and needed people, so I grit my teeth and sent them one of my department managers and one very talented member of my staff. Later, I would often recall how that move was the correct one. “Doing good for others is doing good for oneself,” as they say.

Seeing me desperately struggle for more personnel, I must express my gratitude to Managing Executive Officer Naka, who also served as President of Showa Works (presently SOQI, Inc.*), for sending Yamada-san, and Executive Officer Sugiyama (in charge of the automotive division) for sending Kouya-san to the 3rd Engineering Division. I was overjoyed with their support and I will never forget how grateful I felt when they helped me when I needed it most.

*At the time this was written (currently Yamaha Motor Powered Products Co., Ltd.)

Both Yamada-san and Kouya-san later became key figures in supporting Yamaha’s outboard motors. By the time one year had passed, the 3rd Engineering Division employed almost 50 people. We finally revised our organizational structure, allowing us to properly allocate the various jobs and clearly define tasks.

Showa Works had been handling outboard manufacturing for Yamaha ever since it first entered the industry (photo from the 1960s).

3Starting with Developing Countries

From there, our work moved to finding permanent solutions for the problems causing customer complaints and developing new outboard models to expand our lineup. At the time, we had four models: the P-45 (2 hp), P-95 (5 hp), P-200 (9.9 hp), and P-250 (15 hp). Sanshin Industries was in charge of production and yearly output was just under 60,000 units.

Sanshin Industries was responsible for manufacturing Yamaha’s outboard motors (photo from 1959).

The 9.9 hp P-200 was one of the four outboard models Yamaha had in its lineup at the time.

These outboards were used for recreation in Europe, for fishing and transport in developing countries, and for fishing in Japan. But all of them suffered problems with reliability. Yamaha’s first outboards used motorcycle engines and most users operated them at full throttle for 6 to 8 hours every day on the open ocean.

Outboards were often subjected to prolonged use in harsh conditions (photo from coastal fishing in Japan at the time).

The quality of gasoline was also poor in developing countries in particular, and there were even some areas where users mixed gear oil for cars with the fuel since there was no proper 2-stroke engine oil available. With the engines operating for more than 10 hours a day, it’s really not surprising that they would fail. On top of that, the outboards were being used out on the ocean and constantly exposed to seawater, which would work its way inside the engine and cause rampant corrosion.

The use of Yamaha outboards in developing countries (photo from Pakistan) was the starting point for later model improvements.

Every day began and ended dealing with customer complaints. We got an earful from the sales divisions as well: “You can’t come to us with such an inferior product like this and honestly expect us to get good sales numbers. You guys in engineering keep spouting excuses, but the fact of the matter is the outboards aren’t getting any better.” It was all a total mess and I was so frustrated. I remember thinking to myself, “Damn it, you just watch. We’ll build an engine that’ll never break!”

We slowly but steadily made improvements and resolved the issues causing the complaints, and after a year the outboards were also gradually improving. But I knew the level of progress we made with our outboards still wasn’t enough for them to withstand the harsh use awaiting them in developing countries. It would take time to build an engine that wouldn’t break, but if we halted deliveries and sales until the newly developed engines were ready, we’d lose the markets we’d already worked so hard to secure. The only way to cover this lag time and retain the markets was to improve our post-purchase services as much as possible. After lengthy deliberation, both the engineering and marketing divisions finally agreed this was the best course of action, so I asked Managing Executive Officer Eguchi—he was in charge of sales at the time—to allocate more resources for technical marketing.

I also promised to send somebody from the engineering division well versed in outboard technology to technical marketing, so I made the somewhat painful decision to have Harada-san, the department manager and a key part of our outboard design department, reassigned as the department manager for technical marketing. I did this because I felt that the job was the most important thing we needed for our outboards at the time.

Altering our business methods to compensate for inadequate product reliability with our after-sales services began in earnest with a focus on the developing countries. So our engineers set off together with personnel from technical marketing, running around to every corner of these markets to see them firsthand. My own travels took me from deep in the Amazon in South America to remote areas of Nigeria’s interior in Africa; I saw for myself how our products were being used and I worked hard to improve their reliability.

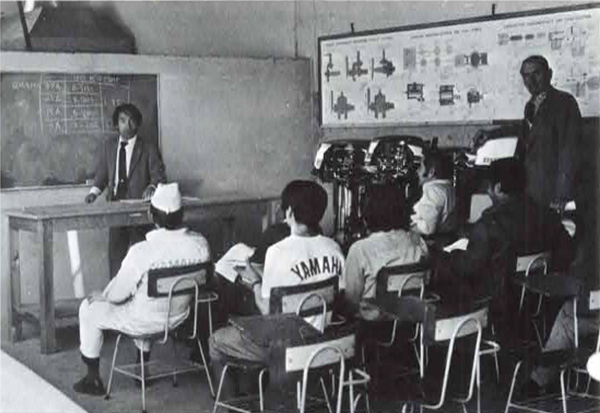

A Yamaha service engineer providing instruction to local mechanics in Papua New Guinea

Classes covering outboard knowledge and technology were also part of Yamaha’s post-purchase services (photo from Mexico).

The reason Yamaha outboards enjoy such a good reputation and have such a large share in most of these markets today is largely based on all the efforts we made back then. The engineering and marketing divisions worked very hard and it was worth it in the end; we knew that if we could ensure reliability in developing countries, there would be no problems with durability in other markets. You could say that the starting point for the quality and the marketing policies of Yamaha outboard motors has its roots in making them a viable business in developing countries.

4Passing Down “Looks and a Little Extra”

Our next task was to develop new models and expand our lineup, and there were two things we did in product development. One was to give our engines a slightly larger capacity than those offered by the competition. Motorcycle and car engines are categorized according to displacement, like “250cc” or “2-liter,” but outboards are categorized by horsepower (8 hp, 25 hp, etc.). With that in mind, we decided to give our new engines slightly larger displacement than the competition, even though they would technically be in the same horsepower class. This slight increase in capacity didn’t affect the size, weight or cost of the engines very much, but it did give each engine some extra leeway in terms of performance, and that yields benefits in a number of areas.

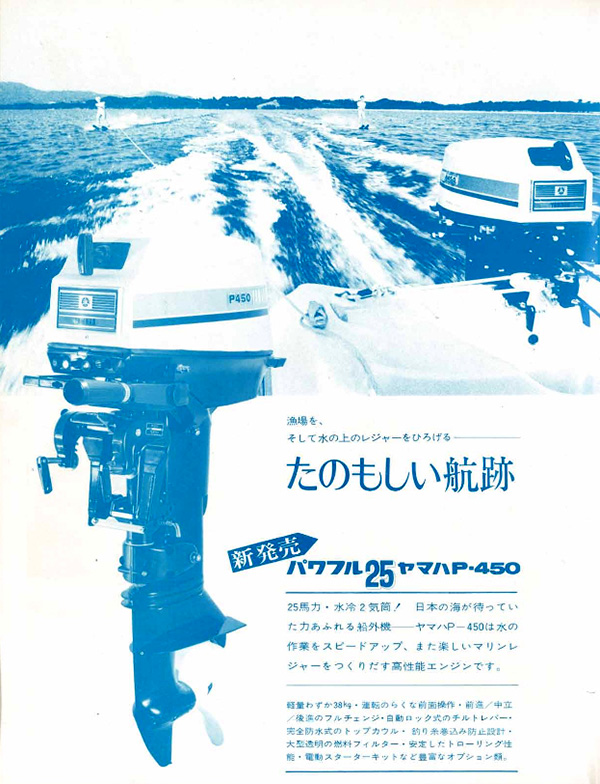

The Yamaha 25 hp outboard engine we later developed had 20cc more displacement than our competitors’ offerings. That model earned an excellent reputation in developing markets and became a long-term bestseller. This was an important design policy we set towards building Yamaha’s outboard lineup and something that continues to this very day.

An advertisement for the 25 hp P-450 when sales began. It later went on to become a bestseller.

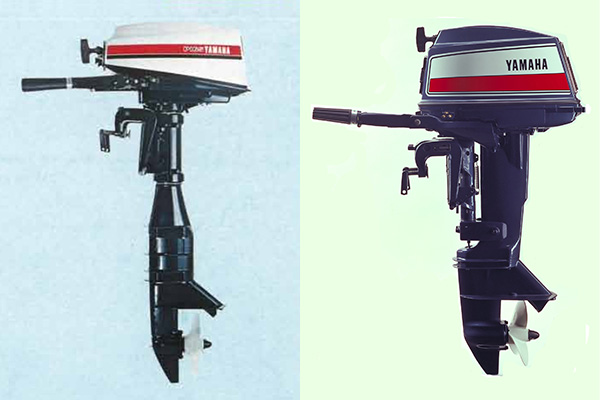

Further, in an effort to quickly change the poor market image our product line had until then, we asked Iwasaki-san at GK Design to completely refresh the paint schemes and graphics of our outboards. We also changed the way we named our models, doing away with our previous method of using the engine’s capacity (P-125 for a 125cc engine) and using horsepower instead like American outboard manufacturers did (15A = 15 hp). This greatly improved the appearance and consistency of our lineup.

Yamaha unified the colors and graphics of its entire outboard lineup and put them on display at the Tokyo Boat Show in 1973.

The earlier two-tone white and grey paint scheme was changed to an eye-catching marine blue with a red stripe and a prominent Yamaha logo. This color scheme of marine blue for the main body and those graphics were used for many years and remained key symbols of Yamaha outboards.

A before (left) and after (right) exterior design comparison