Days Gone By Stories from the Trailblazing Years of Yamaha Motor

5Uncharted Territory: Engineering from the Ground Up

We finally got started on the bike’s structural design, but this was our first-ever attempt at making something from the ground up. So to begin, we gave a great deal of thought toward deciding the order in which what should go where and how. We then decided to create the layout in the following order:

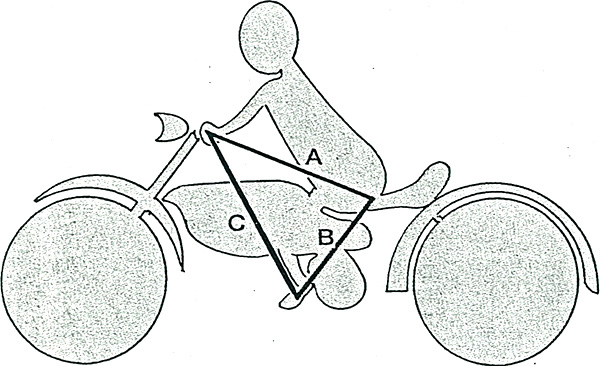

1. Riding Position

Design the triangle formed by the points at which the rider contacts the machine, i.e., the seat, handlebar grips and footpegs, and their respective dimensions to create a sporty, forward-leaning riding position. (We referred to the methods used when setting dimensions for the area around the driver’s seat in a car. Of course, this was the first time this kind of method was used for a motorcycle.)

Riding position

2. Seat Height

Choose a seat height that improves ride stability and sets the bike’s center of gravity as low as possible. Also, make it low enough to allow riders to comfortably reach the ground with both feet.

3. Front Wheel Positioning

There was much consideration about how to achieve the proper balance for the rake and trail, but we concluded that the final settings chosen should place more emphasis on ride stability than things like the bike’s agility for leaning.

4. Rear Wheel Positioning

From our guiding principle of building a compact machine, the wheelbase should be shortened as much as possible, i.e., to the very limit where the desired front-rear weight distribution is still maintained.

5. Wheels and Tires

Aim to use wide tires and small-diameter wheels, and decide sizes based on our manufacturing capability. (We went with 16-inch tires, making this the first motorcycle in Japan at the time to use small-diameter tires.)

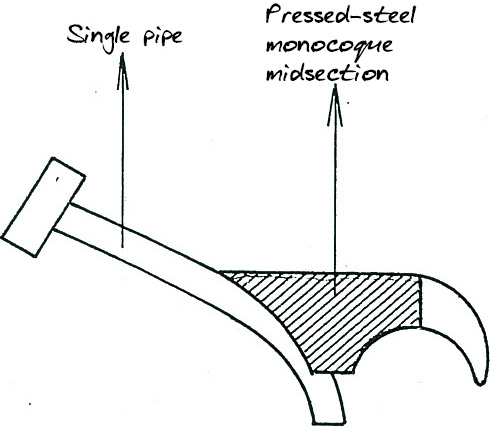

6. Frame Structure

Although we felt the pressed-steel monocoque frame offered the advantages of light weight and straightforward engineering, it also requires a large press to construct. And if we were to use an all-new frame structure like this, we would have to be able to thoroughly strength-test it beforehand, so going this route would present serious difficulties. However, we didn’t want to build a conventional steel pipe cradle frame either (almost all motorcycles at the time used them).

In the end, we took up the challenge of building a completely new kind of frame. It used a single backbone of large-diameter tubing mated to a monocoque rear section integrated with the rear fender. With this design we could perform adequate strength testing and it allowed us to calculate the section modulus of the frame’s various reinforcement components. We also judged that this design would make determining the amount of flex and rigidity needed at different locations clear and simple.

Frame structure

7. Front Fork

We focused on both good handling and stability, so instead of using the leading-link fork that was catching on at the time, we went with a normal telescopic fork. However, we increased travel by 20–30% of the norm for good stability on rough roads.

8. Rear Suspension

Rather than the plunger suspension used on the YA-1 and YC-1, we used a swingarm for the rear suspension for superior handling stability.

9. Seat

With a priority on sportiness, stability and a riding position that wouldn’t change too much at speed or in different road surface conditions, etc., we used a fixed seat—the first of its kind in the Japanese motorcycle industry at the time—instead of the common sprung saddle seat. Added impact absorption to compensate when riding was provided by the aforementioned longer fork travel and the swingarm at the rear.

10. Fuel Tank

After the items above for the layout are finalized, the remaining space the fuel tank needs to fit into naturally becomes clear. In line with our plan to design a compact bike, the tank would be shorter than existing models, but we also wanted it to have a roughly 15-liter capacity, slightly larger than what was on other 250cc motorcycles of the time. To achieve this we would have to make the tank taller, but then the handlebars would come into the equation. This meant we had to make the rear of the tank taller and it ended up looking like it had been put on backwards compared to conventional fuel tanks. The completed YD-1’s tank would later be called Bunbuku Chagama from the Japanese folktale of a raccoon dog that could transform into a teapot. This is a really good example of how a motorcycle takes on its own unique character when form (design) and function are in sync. Because a motorcycle’s fuel tank is a very important design element, the YD-1’s left a powerful visual impression.

11. Engine

We used a 2-stroke twin-cylinder engine, the same format as the Adler MB250 we initially planned to duplicate. This made the YD-1 the first Japanese motorcycle with a twin-cylinder engine.

It was in this order that we began designing the motorcycle, and then started engineering the structure, working out the detailed specifications and finalizing the exterior design, all based on shared principles and ideals. We worked past eleven every night, sometimes even sleeping at the company. It was incredibly hard work, but probably because we were young and the job was interesting, we never found it burdensome. We were a small group of young engineers given a huge responsibility, so we gave it everything we had.

A snapshot on the way to Tokyo in February 1957 to introduce the YD-1

(President Kawakami at the left)

6The YD-1 is Showered with Praise

It was mainly a process of repeated trial and error, but we were able to work on our bike with a prevailing sense of freedom and ease. In retrospect, I think we were very fortunate engineers to have had such an opportunity.

The first YD-1 prototype was completed in February 1957. From the initial planning, it had taken about one year to complete, meaning our small group had developed a new and completely original motorcycle in such a short time. Moto-journalists at the time praised it saying, “This original machine is a masterpiece incorporating all of Yamaha’s technology.” We were ecstatic; it was immensely satisfying for us to know we’d given everything we had and put all our knowledge, skills and passion to the test to build a motorcycle the way we wanted to.

The YD-1 had excellent performance, but shortly after production and sales started we began receiving complaints about the linkages for the twin-cylinder engine’s crankshaft having problems. We had to conduct a market recall on a massive scale for the time, and the truly unfortunate result was that the YD-1 did not enjoy the good reputation we had hoped for.

At the media test-ride event for the YD-1

7The First Bike with a Good Design Award

Having gained some confidence from our work on the YD-1, the chassis engineering team began development of the YA-2, the successor to the 125cc YA-1. Since we long believed that a pressed-steel monocoque frame was the simplest design for a chassis and well-suited to mass production, we had always hoped to use it on a model someday. We thought the YA-2 would be an excellent project to try using a monocoque frame and with less financial expense, so we took up the challenge.

We used a leading-link front fork—common practice at the time—together with a swingarm for the rear suspension, a fixed seat and 16-inch tires, all ideas we took from the YD-1. The engine was a refined version of the one used for the YA-1.

Changing the chassis was the focal point with this model. We thought that using a monocoque frame would open up plenty of benefits unique to the layout, and we made the chassis’ exterior surfaces very smooth—the so-called flush surface. We also took great pains to make the side covers recess so they didn’t protrude outward. We had the image of a car exterior in our minds.

The way we created the styling resulted in a sleek and beautiful machine, nothing like previous motorcycles. In fact, the YA-2’s styling was what made it the first motorcycle to win a Good Design Award as a masterpiece of industrial design. The judging for the inaugural Good Design Awards were held at Korakuen Hall in Tokyo, and products from various fields were put on display. I remember standing in front of the YA-2 and explaining its development concept and features to the judges and them rating it very highly.

At a time when the Japanese market was flooded with copies of European and American products, our burning desire to create a new product led us to build the YD-1 and YA-2. Even today, I have vivid memories of the work we did and the experiences we had.

The YA-2 was the first motorcycle to win the Good Design Award.