Tempering the 16-inch Wheel with an Anti-16-inch Approach

(Return to Part 1)

In 1984, the same year that the FJ1100 debuted, Yamaha launched the FZ400R for the Japanese market. This was Yamaha’s first 4-stroke racer replica model. Because the RZ250 that revived the 2-stroke supersport category had a design that overlapped with that of the successful TZ250 and TZ350 World GP production racers, it caused the other manufacturers to follow suit by introducing racer replicas modeled after GP machines one after another.

Models like Honda’s VT250F and Suzuki’s RG250Γ—built to resemble the NR500 and RG500Γ, respectively—were designed to first of all have cowling shapes similar to race machines. That meant their handlebars would take on the same extremely low-set position as the race machines, and on top of all that, the efforts to bring these replicas closer to the race bikes escalated to the point where they were being developed simultaneously with the

“SP class” race machines [a Japanese race category at that time], as everyone knows. Yamaha introduced the FZ400R at the same time this trend was emerging in the 400cc 4-stroke category. This marked the start of an era that would see the trend continue into the later years of the 1980s, initially with models like the GSX-R400, VF400F, CBR400R, and followed by the GSX-R750, VFR400R, FZR400R and FZR750R.

FZ400R (Released in 1984)

The FZ400R debuted as Yamaha’s first full-fledged 4-stroke racer replica. It faithfully reflected the boom in racer replica models at the time, such as having a tachometer located in the center of the instrument panel instead of a speedometer, just like on a full-on race bike. While it had a small-diameter 16-inch front wheel in line with the trends of the time, it wasn’t a bike focused on quick handling—a trait making it very much a Yamaha machine. There were many discussions held within the company regarding this, but as this kind of handling represented the conscious intentions of the test riders, it would be the direction Yamaha Handling would take into the future.

It can be said that the biggest characteristic of the racer replica boom was not simply the efforts to make each model’s exterior form and structural layout as close as possible to the actual race machines but the adoption of a large number of the latest technical features worthy of an advanced replica model to serve as convincing sales points. This became what the different manufacturers began competing with each other for, essentially turning into a “feature contest.”

One of the elements considered a must during the early stages of the racer replica era was a 16-inch front wheel. Until then, it was the standard for supersport models to have 18-inch wheels front and rear as it was in racing. But then in the late-1970s, French tire manufacturer Michelin worked with Team Gallina from Italy that was running Suzuki factory bikes in the World GP to try something new—reducing the diameter of the front wheel and tire to 16 inches.

The 1970s brought not only increases in engine performance in the road race arena but also a dramatic jump in cornering performance due to advances in tire design, including the advent of the first racing slicks. This in turn led to a new type of racing style were cornering performance was the determining factor for competitiveness. This was evidenced by the appearance of racing legends like Kenny Roberts and Freddie Spencer, who would run skillfully through the corners while holding amazingly deep banking angles for the time. These shifts brought even more importance to focusing on cornering performance. What the riders now wanted in this new type of racing style was the lightest and sharpest responding characteristics possible when leaning the bike over into a turn. At the same time, this naturally brought more focus to things like achieving enough grip during hard braking and when banking the machine into a turn.

This then inspired the move to smaller diameter front wheels to try and enable lighter, more agile response by reducing the amount of inertial force in the bike’s roll direction when leaning it into a turn. Furthermore, efforts were made to increase grip during braking and mid-lean by adopting low-profile tires with wider tread surfaces. These were the initial aims of developing race machines with 16-inch front wheels.

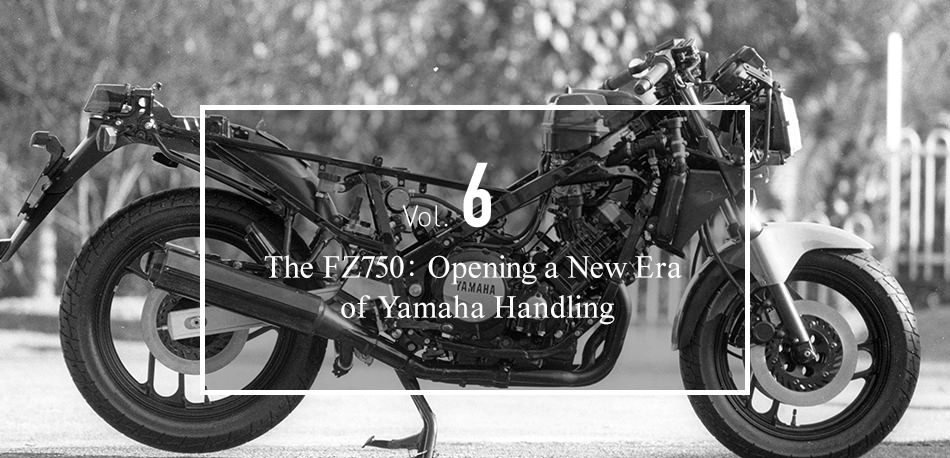

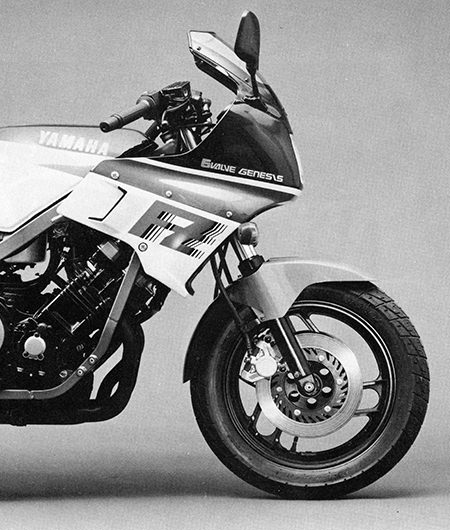

FZ750 (Released in 1985)

The “Genesis” engine mounted on the FZ750 had five valves per cylinder, and a bore of 68 mm and stroke of 51.6 mm for 749cc of displacement. The overseas market model had a maximum output of 102 PS at 10,500 rpm, and a maximum torque of 8.0 kgf·m at 8,000 rpm. It had a wheelbase of 1,485 mm and weighed 209 kg. Setting a caster of 25°30’ and trail of 94 mm created a new and palpable ride character that was light and agile at mid-range speeds and below, but had a feeling of stability that grew at higher speeds. This was the unique result of the testing group’s focus on bringing usability to Yamaha’s big bikes. While many rival models had full cowlings, Yamaha chose to go against the trend and adopted a half-cowl with a refined impression that displayed the bike’s muscular form as well as creating a front face that clearly belonged to the supersport category. This design was uniquely Yamaha in that it did not cater to any market trends at the time.

However, as teams tried to put 16-inch front wheels to use in the World GP through trial and error, they found that the smaller diameter wheel proved advantageous on some tracks but not others. So, the conclusion was reached that the 16-inch front wheel alone was not an all-around solution for better race performance. Another factor that has to be mentioned here is the simultaneous shift to radial tires, but as everyone knows, entering the 1990s, the race world had arrived at the current size standard of 17-inch wheels for the front and rear.

Nonetheless, the “mission” of race replica model development at the time was to feed the technical advances of World GP race bikes back into production models as quickly as possible, and a new trend of using 16-inch front wheels—even with an 18-inch wheel for the rear—emerged with the VT250F in 1982 and continued until around 1984. “From the product planning stage of the FZ400R, we were told that if we were going to build a race replica model, a 16-inch front wheel was basically an absolute necessity, though Yamaha had never used a 16-inch front wheel until then,” recalls Jiro Izaki. For him, having finished the development project for the FJ1100 and now beginning to work on the FZ400R, this was a point of major concern.

“To tell the truth, I couldn’t get used to a 16-inch front wheel. From my perception, it was surprising how little steering effort was needed and how light it felt. I wondered if building a machine that leaned over so sharply and quickly was really the right thing to do,” confides Izaki. “I had always been told by my seniors that a bike depended first and foremost on the feeling of assurance it gave the rider, and my perceptions were also built on that. It lacked a trail feeling, and I didn’t like the moments when it felt as if the front wheel was slicing through the air [with a feeling of little grip]. I couldn’t ride a machine with a 16-inch front wheel that I felt scared with, and I believed that we shouldn’t put such a machine on the market.

“So, we worked to set a front alignment that felt stable. That’s why we didn’t use the dimensions of other bikes as reference. For the chassis rigidity as well, we changed the rigidity balance of the frame and the swingarm to accommodate this completely different combination [of wheel sizes]. We were working on these elements and trying new things right down to the wire, and that’s why it was just before the model went into production that we changed the cross-sectional shape of the swingarm and re-developed it. We were given a lot of flak for that,” recalls Izaki.

“What’s more, this spec change was one that involved a size that didn’t leave enough clearance from a design standpoint with the manufacturing technology in use at that time. By normal standards of the day, it had dimensions that couldn’t be assembled smoothly on the line. Formerly, the design engineers had the leading role in chassis design because they would decide on the rigidity balance during the initial design drawing stages and then the testing team would just be responsible for adjusting the alignment. But from around this time, the flow of development had begun to change,” explains Izaki.

In fact, the industry had indeed entered a new era in which not only handling stability but also handling character and quality were now points of evaluation. Furthermore, the reason behind the Yamaha Handling reputation was surely that Yamaha developers stuck to their long-held values and resisted being swayed by the popular trends of the times.

“We had finally managed to get even a 16-inch front wheel model to have the stability and sense of contact with the road that we felt was necessary. But since the selling point for all the other replica models was quick and sharp handling, the fact that our model felt heavier at times when simply comparing it against them led some people within the company to say that this feeling wasn’t what having a 16-inch front wheel was all about,” Izaki notes. “But for example, let’s say I was going to the absolute limit while track testing and for some reason I fall. If it’s between falling when I’m ready and prepared for that possibility or falling suddenly when I’m not expecting it, I definitely don’t want it to be the latter. In this sense, this is one more area where we learned important lessons with the FZ400R,” concludes Izaki.

Even in a RIDERS CLUB article at the time, we reported that this model was completely different from the other offerings regarding the feeling of lightness and agility with a slightly more big-bike feeling to the handling—something not typical of 400cc racer replicas. Needless to say, the FZ400R became a popular model thanks to the good feeling of stability that made it easier to ride than the other replica models.

FZ750 at the Daytona 200 (1985)

The FZ750 was unveiled at the IFMA motorcycle show in Germany in the autumn of 1984. In March of the following year, it made a speedy debut in the Daytona 200 in the United States. Despite being simply equipped with kit parts, the American Yamaha team managed to finish 5th in the race that year with one of their bikes, and Eddie Lawson would win the race in 1986 riding one.

Greater Performance Brings Greater Focus on Actual Usage

From 1985, Yamaha began to build its lineup of models powered by the 5-valves-per-cylinder “Genesis” engine that would become the mainstay of Yamaha power units for years to come. The first model released with this engine was the FZ750. This bike can be ranked as another model that helped build the legacy of Yamaha Handling. I say this based on the impression I got the first time I test-rode it. The FZ750 had a great feeling of stability in the high-speed range but you could also lean the machine over in the mid-speed range and lower with assurance. The new and incredible feeling this well-balanced handling brought was something I’d never experienced before. “I was thrilled with the way the 5-valve engine quickly gave you a strong burst of acceleration, even when opening it up from partial throttle. Experiencing that gave me a renewed awareness of what my senior test riders from the XJ650 development days always told me: the engine is a big factor influencing handling performance. Thanks to things like the knowhow we had gained with the lateral frame, the FZ750 chassis felt good right away from the basic design stage and it required very little work in the development testing stage,” says Izaki.

“Among the big bikes until then that had a 16-inch front wheel, we got a good impression from the Honda VF750F, so that became one of our targets.” At the time, Honda had added a new V4 engine to its supersport lineup to supplement its traditional in-line 4-cylinder engines. The V4 had a gentler engine character, so while the VF750F also had a 16-inch front wheel, it had handling characteristics with a composed feeling of stability. “Compared with the FJ1100, which was technically a supersport model but one aimed at riding straight and fast down the German Autobahn, our aim for the FZ750, with new factors like its different engine character, was to develop a model with handling that made it really fun to ride. What I mean is the fun of working the throttle especially when exiting a corner; that’s what we were aiming for. Thanks to the good basic design of the chassis, we got very positive evaluations for it without having to do much in the way of enhancing its feeling of agility, and there were no problems in the area of rigidity either,” Izaki continues.

“As for performance on the test course, the FZ750 felt especially good and fun to ride when accelerating toward the hairpin while still in a lean coming out of the S-curve. It was great. It was also around this time that we were establishing simulations based on the knowledge that with handling, a slight feeling that the bike was quickly falling into a lean on the test course—something that had come to have negative connotations for us—could actually feel just right when riding on public roads. In the same sense, if the handling felt well balanced on the test course, it would tend to feel a little too heavy on public roads,” comments Izaki.

It’s common sense that a manufacturer’s new-model development be conducted in utmost secrecy, and the development test-riding is mainly done on the manufacturer’s own test course. But if development is based solely on performance on a track, the feeling when riding on public roads will inevitably be different. As a result, there will be cases where the end users will not be able to enjoy the same handling that the test riders experienced. That’s why Jiro Izaki insists that the important thing is how the bike feels when users actually go out touring on it, and the bike’s value will be determined by how much enjoyment they get while doing so.

“In order to use the test course as if it were a public road, we imagined there was a center line down the track,” explains Izaki. “Instead of taking the usual ‘out-in-out’ lines you would use to run through corners on a racetrack, we stayed on one side of the track and did things like going through the corners over and over using ‘in-in’ lines. Of course, we do this riding on both the right-hand side and the left-hand side of the road. We also mustn’t forget the importance of the late Ikujiro Takai (Yamaha’s ace rider of the 1980s) getting Yamaha to build a chicane section into the test course. The original layout was basically a high-speed course, but he insisted that not all the courses in the world have so many sweeping corners. I heard that was why he wanted to create a place on the course where you had to brake hard while going from top gear to low gear. This certainly is a specific factor that influenced the direction of Yamaha Handling,” recalls Izaki.

“Takai always thought about the motorcycle in very specific terms, and when we and the racer group were taking turns using the test course, he would sometimes come over to us on the paddock and take our test bikes out for a short ride and give us his comments about them,” Izaki continues. “Racers usually don’t have much interest in production models, but Takai would give us his honest opinions, saying things like, ‘Yeah, this feels good. That’s how a motorcycle should feel.’”

As we mentioned in the previous article how the handling and concept of the TZR250 were based on those of the YZR500, from things like the experience of competing with a Yamaha factory machine also using a 16-inch front wheel, Yamaha had reached the conclusion that even with a World GP machine, you couldn’t ride fast unless it had handling that was in tune with the rider’s perceptions and gave the rider a feeling of assurance. This was reflected in the attitude of Takai, who had also been a development test rider during that difficult period of transition. This is certainly a uniquely Yamaha episode.

This is how Yamaha went through the period of dominance of the 16-inch front wheel. Instead of running in the direction of excessively sharp handling and agility, the company stuck stubbornly to its traditional Yamaha Handling values of basing its handling on stability. In the ensuing era of the radial tire and the next generation of bikes from rival manufacturers that also gained increased stability, Yamaha would continue to take a path of its own that would once again set it apart from the competitors.

(Continues in Vol. 7)

FZ750 front assembly

The FZ750 also adopted a 16-inch front wheel, and this naturally meant that its handling had a good feeling of stability. As you can see in the photo, while it had a 16-inch front tire, the outer diameter of the tire was quite large. This was an early indicator of the change to 17-inch wheels that would arrive later. While it was not a huge sales hit, it was praised for its high-quality manufacturing and good design. Many of them are still running strong and can be seen out on roads today.