The FZR1000: Ease of Handling Still Takes Priority with a Racer Replica

(Return to Part 1)

The racer replica boom wasn’t a phenomenon limited to Japan. It extended to large-displacement supersport bikes in Europe as well. In 1987, Yamaha introduced the replica-styled FZR1000 to the European market, boasting an aluminum Deltabox frame and a top speed of 270 km/h. At the time, racer replica models featured extraordinary specs in areas like their lightweight chassis, and their major sales point was their light and sharp handling that could never be expected from a conventional big bike. However, even with racer replicas, the development teams at Yamaha were averse to handling that was overly sharp, and they developed their replica models with handling characteristics focused on a feeling of stability for ease of use on winding public roads. This policy was the result of the knowledge they gained during development. They knew that giving a bike handling response that was too quick and responsive brought the danger of strong kickback from the front wheel. The FZR1000 and its subsequent model updates were based on a methodology of improving the machine’s overall balance in order to achieve light and agile handling that felt just right. In this way, the model continued to undergo a very Yamaha-like evolution.

Ken Nemoto test-riding the FZR1000.

Riding Fun on Secondary Roads

With the debut of the FZR400 mounting an aluminum Deltabox frame in 1986, the racer replica boom in Japan had reached its peak. Then, its popularity seemed to set off a racer replica boom in Europe as well. Of course, unlike the 2-stroke 250cc and 4-cylinder 400cc models sold in Japan, the models that became the focus of attention in Europe were big bikes with displacements of 750cc and up. The model that sparked this boom was none other than the Suzuki GSX-R750 that appeared in 1985. As we all know, its arrival made waves throughout the industry with specs that were previously unthinkable in a big bike, like its aluminum frame and incredibly light machine weight of less than 180 kg. Suzuki followed this up with its GSX-R1100, thus expanding its racer replica strategy into the liter-bike range. The styling of these models in particular, with their dual headlights modeled after the machines that competed in Europe’s popular endurance races like the 24 Hours of Le Mans, made them such a big hit that they posed a real threat to Suzuki’s rivals. At the same time, it marked the beginning of a major change in big-bike handling performance.

With big bikes until that time, the main question was how well they could handle very-high-speed cruising on expressways like the famous German Autobahn. No one even considered the prospect of trying aggressive cornering on bikes adopting a big, heavy chassis for good stability at those highway speeds. However, the GSX-R proved that a big bike could still have light, agile handling—something that nobody had thought possible until then. This resulted in the development of big supersport bikes in two different directions: racer replica types with great cornering performance and tourer types designed for comfortable high-speed cruising. Of course, Yamaha wasn’t about to stand quietly on the sidelines. Yamaha entered this new arena by developing and releasing their first big-bike racer replicas in 1987: the FZR750 and the FZR1000. “The hot-selling GSX-R750/1100 were definitely a big influence when we started development of the FZRs,” recalls Jiro Izaki, a central member of Yamaha’s testing group (Yamaha’s Road Testing Unit, 2nd Project Engineering Division at the time of the interview). However, Izaki said he’d actually test-ridden the GSX-R and felt it was a kind of bike that Yamaha wouldn’t make.

“I went to Europe and tried riding all kinds of motorcycles, with the added intention of gathering information to help determine the direction for our development. The GSX-R was one of the bikes I rode. It had light and sharp handling that felt nothing like a big bike at the time, but my impression was that, in use on public roads and not on the circuit, it was just too aggressive for us at Yamaha to accept,” said Izaki. “With the steel-framed FZ750, we had concentrated on high-speed range performance, and while I was riding in Europe, I found the continent to be the best environment for motorcycle riding. Besides the high-speed expressways, the roads you took on the way to the expressways were also fun to ride on. In contrast to the expressways that were our primary target at the time, we called these ‘secondary roads,’ and in Europe we found them to be really great fun to ride on,” he continued.

In Europe, there are definitely a lot of truly enviable roads with mid- to high-speed turns with good visibility ahead that you can zoom through with delight on a big bike without having to fully lean the machine over. From the winding roads in the Alps mountain range to country roads with little traffic, you will find places all over Europe where you can enjoy motorcycling to your heart’s content. “The FZR400 that we had developed before the FZR1000 was a racer replica model intended for racing or track riding. But with the FZR1000, we decided to develop a bike that would be fun to ride on these secondary roads that European riders were enjoying on their motorcycles,” recalls Izaki.

FZR1000 (European spec model released in 1987)

This model adopted features like the first aluminum Deltabox frame ever on a big bike, and had the form of a real racer replica model. However, its handling was not based on a blind pursuit of agility, but a quest focused on stability to make it a bike that was fun to ride on secondary roads. The dedication to this goal is evident in the positioning as well as angle setting of the handlebars.

Izaki said that he did things like talking with local dealers and trying to go touring in the same way as the actual users did. What he grasped after riding all around Europe like this was that there’s no way the ride will be fun if you’re on a machine that makes you feel insecure every time you enter an unfamiliar turn, and general users will surely feel the same way. He said that this realization became the determining factor in deciding the limit to how light and sharp they should make the handling, even with a racer replica model.

Something else quite characteristic of touring in Europe is how frequently the weather changes; just when you think it will be a sunny day, rain suddenly starts to fall. In these circumstances, if sharp handling that might be good on dry pavement in fair weather actually leads to anxiety when the roads become wet with rain, it’s simply a factor preventing a bike from having excellent handling overall. “I tried a variety of bikes, and what I found was that, depending on the bike, it might be very fast in good conditions but had to be ridden at a much slower pace when the conditions worsened. That was a very valuable lesson,” Izaki said.

Even if a bike was designed and built as a racer replica, touring was what most users would actually be doing on it. The fact that they would be carrying luggage on it when they went touring also meant that you couldn’t drastically narrow down the bike’s intended use conditions. Like I’ve mentioned numerous times before in this series, this is yet another factor [emphasizing actual use conditions] that Yamaha refused to ignore in the design of their sport bikes over the years.

“Eventually, we found that there wasn’t much difference between what we wanted in a bike and what the test riders we enlisted over in Europe were asking for,” Izaki noted. Based on their experiences in Europe, numerous development tests were held using the curves of the test track as if they were the turns of the winding roads in the German countryside.

Valuing a Bike’s Feeling of Assurance

“Since this was to be a replica model, the model concept and the use of an aluminum Deltabox frame were a given. But it wasn’t easy to actually bring it all together into the kind of bike and performance we wanted,” added Izaki.

Of course, building a machine capable of reaching speeds of 270 km/h and ensuring solid stability in this incredible speed range were prerequisites. Furthermore, they were adding another objective for this bike—to achieve cornering performance in the high-speed range that the rider could really enjoy. They had a new weapon in the radial tires, but these were still in their early stages technologically, and although there was a stock of experience in using an aluminum Deltabox frame on race machines, this would be its first application on a large and heavy big-bike model. Also, there were other factors like the performance-determining engine, which needed not only sheer power but also smooth performance that a rider could fully enjoy when going through the rev ranges. All of this meant they had the difficult task of meeting a wide range of performance demands for the new model.

So, what did they aim for specifically when trying to create handling characteristics they felt would make a bike fun to ride on secondary roads? Izaki explains: “What we concentrated on most was the feeling when you first lean the bike over into a turn. We tuned the handling so that there was a natural feeling to the steering that the front wheel took when the machine was being leaned over into a turn. This is an absolutely essential factor for handling that gives the rider a feeling of assurance. For example, if I’m riding and it feels like the front wheel is cutting in by itself, I can’t feel at ease on the bike. I just can’t allow a bike to be put on the market if I myself feel insecure on it. And, if there isn’t a strong feeling of assurance, it won’t be a fun bike to ride.” This is the philosophy that Izaki has always followed.

“We were able to apply the knowhow we had gained from putting the 16-inch front wheel into practical use on the FZ400R. The characteristics of the tires play a big role [in handling], and in terms of the tire characteristics like the relationship between the profiles of the front and rear tires, we had the fewest problems with Michelin at the time. The faster you went with them, the more you could feel the tires’ [solid] contact with the road. This was a very important factor,” commented Izaki.

“When dealing with handling characteristics, it’s not enough to make judgments solely on cornering performance. For example, there’s the braking as well. Of course, you have to have enough stopping power to brake from 270 km/h, but the other important thing is, if the feeling you get after releasing the brakes when getting ready to enter a turn isn’t good, you can’t make a good approach to the corner. Engine braking also influences cornering performance. Another important characteristic is the controllability of the engine’s response when you open up the throttle after going through a corner at partial throttle (throttle opening that causes neither acceleration nor deceleration). For real enjoyment of cornering, there are many other factors involved besides these,” added Izaki.

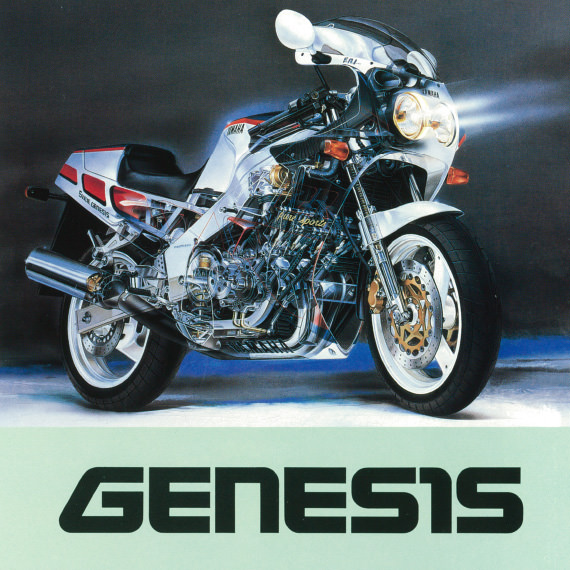

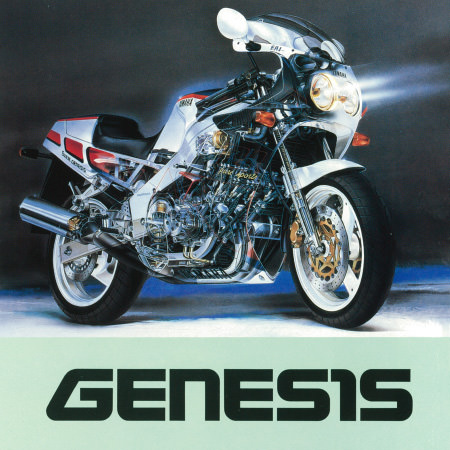

A cross-sectional illustration of the FZR1000 in an overseas-market Yamaha catalog when it was first released.

Although it’s easy to say that a machine has “enjoyable performance on secondary roads,” these comments show clearly that actually building one that achieves that goal takes an exceptional amount of effort.

When it comes to cornering, another element we are concerned about is riding form (posture/position). Being Yamaha’s first big-bike racer replica, it had a riding position that was meant to accommodate the low-down crouch for riding a race bike, but was that considered a given during the development tests?

“We stuck with the basic riding style of leaning with the machine while gripping the bike with the knees. That’s because it’s the best way to control the machine with certainty. Our senior test riders were always strict about checking to make sure we kept our toes pointing straight forward when riding—in other words, that we didn’t get sloppy and start pointing our legs outward.

“That’s because we set up the handling characteristics without the premise of a riding form with a full forward crouch, and then let riders work out the riding style they preferred afterwards. Of course, for us [test riders] too, leaning our bodies [into the turns] and having our hips slightly off to the side of the seat and our inside leg opened out to a degree helps us ride through the turns more easily, and we weren’t too strict about what we were taught,” Izaki noted. “Concerning the forward-leaning riding position on racer replica models, we were careful to never set the position so deep that the rider had to strain to look up all the time. For example, there was a case where just raising the handlebar position by one bar width suddenly made the riding posture much more relaxed and the bike was easier to ride. Knowing that actual users would often go touring on the bike, setting it there was really the only acceptable choice,” he added.

This was the very Yamaha-like methodology that was used to set and fine-tune the specs and performance of the FZR1000. However, during the track testing stage of the development, there was one issue that emerged concerning the handling that would force the team to make a critical decision.

At a Crossroads: No Hesitation in Choosing Stability

It was a phenomenon known as “kickback.” This occurs when the bike passes over an undulation in the road surface at a certain angle and with a strong amount of drive force to the rear wheel. The bike’s rear end sinks deeply, subjecting the chassis to large forces, and the front wheel jerks strongly to the left or right. It’s something that rarely happens because a number of complex conditions all have to come together at the same time. Still, the development staff took this incident very seriously. Although they were aware that it was something that occurred very rarely, they wouldn’t let it pass. It seemed to be the result of a number of intricate factors, including the more responsive handling character, the high rigidity of Yamaha’s first aluminum Deltabox frame for a big bike and the characteristics of early radial tires.

Today, it’s a phenomenon that has become commonplace with race machines as they are expressly built for sharp handling. In fact, it is something that can potentially happen with any type of bike due to the inherent structure of a motorcycle: a chassis with a front and rear wheel.

Yamaha’s Fukuroi Test Course when the FZR Series was under development.

However, the Yamaha development team believed it was something that must never happen with a bike that the general customer was to ride. That belief led them to quickly change their goals to creating a handling character with a high level of stability that moderated the degree of agility they were aiming for originally. It was a move meant to prevent kickback from occurring.

“We changed to a direction of increasing stability without hesitation. Values differ, and there may be a methodology that puts priority on light, agile and sharp handling characteristics, but that’s something we cannot do. There has always been an ongoing debate in the company about what constitutes ‘heavy’ handling and what level of handling is considered ‘light,’ but this issue was on a completely different level. But, I felt that increasing stability was what led to the reviews in motorcycle magazines and the like creating the image that Yamaha was against bikes that felt light and agile. Among them were some harsh criticisms saying Yamaha should just hurry up and make bikes with the same kind of light handling as its rivals,” recalls Izaki.

There was a hint of frustration in the way Izaki talked about these events. It can’t be denied that some motorcycle magazines had a bit of a misconception that the kind of light, dynamic performance that had been unattainable until then in the big-bike category could now be achieved simply with the light chassis of the replica models. There was a tendency to think that lightness in itself made a bike “good” or “outstanding.”

Nonetheless, it can surely be said that this was not only a “typically Yamaha” kind of decision but also one that was symbolic of what the company had always placed priority on with regard to handling. Due to this sequence of events in its development, when the FZR1000 was finally released, it became a model that would win Yamaha a group of devoted fans—including ones with no previous Yamaha connection—who came to prefer big bikes that had a feeling of assurance in their handling and performance.

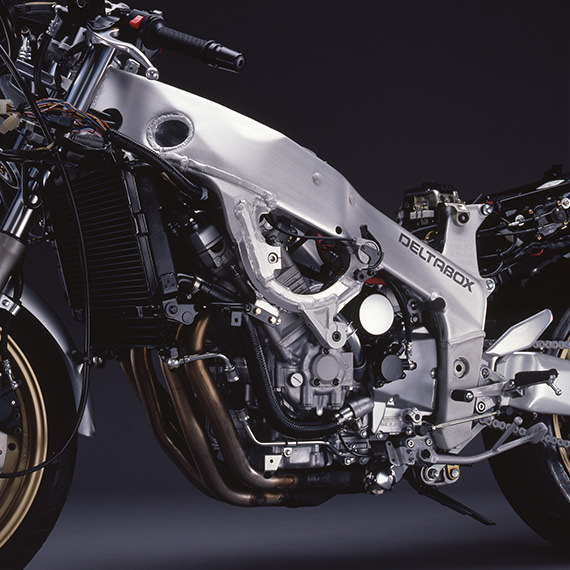

Improvements to Achieve Excellent Balance

“Of course, we didn’t give up there. After that, tires meant for big bikes were further developed and size settings that could bring out the inherent benefits of the low-profile radial tire were found, making it possible for us to solve several issues. With regard to the chassis, advances in three-dimensional stress analysis technology made it possible for us to reduce torsional rigidity on the aluminum Deltabox frame while increasing lateral rigidity. These improvements were applied from the 2nd-generation FZR1000 model released in 1989.

“Compared to the existing model, I would say we brought the handling to a new level of maturity by improving the bike’s overall balance rather than trying to aim for lightness and agility,” explains Izaki. The 2nd-generation FZR1000 continued use of the same basic [exterior] design as the existing model and added more curved surfaces for a smoother form, but attention was focused on not drastically changing the bike visually. That meant that while its debut was not a sensational one, there was unanimous praise for the advancements in its handling. In our review of it in RIDERS CLUB magazine as well, we praised it as having flawless balance that gave it perfect handling and set it clearly apart from the competitors’ models. It stood out with its lightness that wasn’t so excessive that it brought sudden changes of handling character, and steering characteristics that remained neutral when you leaned the bike over in almost any situation, making it easy to ride.

FZR1000 (European spec model released in 1989)

The advent of low-profile radial tires in sizes that allowed motorcycles to take full advantage of their benefits and a full review of the aluminum Deltabox frame’s rigidity gave this updated FZR1000 big improvements in overall balance compared to the previous generation. It was hailed as the best-handling liter-class bike at the time.

This character that was easy to get used to and the steady feeling of assurance that didn’t change with different road conditions made riding so fun that riders would forget they were taking corners on a liter-class bike. “This FZR was produced concurrently with a 600cc export-spec version of the FZR400R. It took the Japanese-market 400cc replica model as a base, albeit with a steel frame [instead of an aluminum one], and the engine’s displacement was bumped up to make it more powerful. The added feeling of power that came from the 600cc engine meant that, in simple terms, the balance shifted to one where the engine outpaced the chassis, which made for a fun and sporty ride. They were also easy to use, and 600cc bikes are a popular class in Europe. However, with a big bike, the chassis always has to outperform the engine. I believe that this is the pivotal point when it comes to balance in a big bike, even if it’s a replica model,” notes Izaki.

The long-standing premise of Yamaha Handling regarding the relationship between the rider and the bike is that, first of all, if the bike’s handling and performance characteristics aren’t in tune with rider perceptions, they will not be able to ride with assurance. When a rider feels assurance in controlling the machine, that’s when they can enjoy riding even at a higher pace.

Even through the racer replica era, a revolutionary period of motorcycle handling, Yamaha stuck with this basic principle. Back then, many bikes were built to provide a level of stimulation so strong that many riders, depending on their motorcycling experience and perceptions, felt such bikes were difficult to handle. In contrast, Yamaha pushed forward with its own approach to motorcycle handling. Considering the fact that the industry has been making a return to placing priority on how easy a bike is to ride—regardless of the type—makes us appreciate anew the importance of Yamaha’s philosophy of building user-friendly bikes that are in tune with rider perceptions.

The aluminum Deltabox frame of the 2nd-generation FZR1000 had less torsional rigidity and greater lateral rigidity. Its improvements were extensive, including a 2 kg weight reduction. The forward incline of the engine’s cylinder block was also changed from 45° to 35°.

In this way, having passed through the boom in racer replica bikes that took the motorcycle industry by storm—sometimes standing alone in stark contrast to its competitors—Yamaha would go on to respond to the “naked model” trend that had begun in Japan by launching the XJR Series, models with a unique handling character that would once again set Yamaha apart the other manufacturers.

(Continues in Vol. 8)

The FZR1000 and FZR400 in an overseas-market Yamaha catalog.