Vol. 7 Staying the Course: The FZR400 and FZR1000

By the middle of the 1980s, the racer replica boom that had begun with models sporting full cowlings to simply resemble real race machines was escalating relentlessly to the point where the manufacturers were competing to produce models that were as close as possible to actual race bikes. The zenith of this trend was when the replica models came to be developed alongside the factory machines for the All Japan TT-F3 (Formula 3) road racing class, which was contested on modified 400cc production models. Yamaha believed that the aspects desired for a production motorcycle and a race machine were profoundly different and had resisted marketing an all-out racer replica. But as the industry showed no signs of moving on from this trend, Yamaha could no longer stand by and watch its rivals dash ahead, and the decision was finally made for Yamaha to develop its own “road-going racer.” The result was the FZR400 released in 1986. To create the image of advanced technology, it was equipped with components like an aluminum Deltabox frame as well as the extremely wide, low-profile tire design necessary for radial tires to function effectively. A light and sharp handling character was also a development goal. While most believed that the faster a bike was on the track the better, the Yamaha development team had a number of other concerns they felt compelled to deal with.

*The article below is a translation of a RIDERS CLUB article originally published in 1996 and contains additions and revisions.

Ken Nemoto

Born in Tokyo, Japan in 1948.

Withdrew from Keio University's Faculty of Letters.

He began riding motorcycles at age 16, won the 750cc All Japan Road Race Championship title in 1973 and competed in the World GP from 1975 to 1978. After returning to Japan, he served as the editor in chief of RIDERS CLUB magazine for 17 years and also served in producing a wide variety of hobbyist magazines. Today, he competes in the AHRMA's classic motorcycle races at Daytona Speedway as part of his life work.

Escalating to Development alongside Race Bikes

The aim of using a small-diameter 16-inch front wheel as the representative feature of models in the early stages of the replica boom was to give the bike a light and sharp feel when leaning in to bank through a turn. Yamaha also followed this trend and adopted the 16-inch wheel, but they avoided giving their machines the excessively sharp handling of their rivals’ bikes. This was based on Yamaha’s belief that, unlike riding to the absolute limit in the world of racing, the general rider will feel greater assurance and enjoyment riding a bike with a handling character based on a feeling of stability, and in the end, that will enable them to ride faster. It goes without saying that the reason Yamaha bikes had the image of being good through corners and that the company was seen as the leader in handling performance from the 1960s was because Yamaha had always stuck to their policy of designing and building bikes specifically from a rider’s perspective. However, an era that threatened to uproot the very foundation of this Yamaha philosophy had arrived—the replica boom. The popularity spawned by this trend seemed to be never-ending.

The racer replica trend first began with models designed to convey the image of a race machine by equipping them with full cowls. But it rapidly escalated into a competition to go beyond mere appearance and create models that were as close to real race bikes as possible. Sparked by the adoption of an aluminum frame on Suzuki’s RG250Γ, the Japanese manufacturers were soon fitting their replica machines with one race-bred feature after another, simply because they were used on their real race machines. Before long, they were producing machines that could be rightly called “road-going racers.” Naturally, the users were more than pleased to have the chance to own and ride these new models that had the same kind of functions and beauty of the race machines they admired so much. The competition between the manufacturers went to new extremes. This was especially true in the hotly contested 400cc category. The popularity of All Japan TT-F3 (Formula 3) class racing that pit modified 400cc production machines against each other was running high, so winning in this class had a direct influence on the popularity of a model in the market. This meant that every manufacturer went all-out in developing their 400cc offerings.

As racing in the TT-F3 class was done with modified production models, it would naturally be an advantage to have a high level of racing performance potential in the base production model to begin with. So, the most effective way to develop the production model would be to design and engineer it with the assumption that it would be used for racing. This led the manufacturers to take their development projects to the extreme by developing the production models simultaneously with their race machines. The methodology was not to build a production model for use on public roads, but to first build a racing machine and then adapt its specifications for use on the street.

Although Yamaha had minimized superficial racer-like appeal in favor of more substantial design and engineering advances with its FZ400R and TZR250 replica models, it could not ignore the market trend this time and decided to bring in every advanced feature at its disposal to create a machine that would put it a big step ahead of its rivals. The result was the FZR400 and its TT-F3 racer equivalent, both developed and unveiled in 1986.

Toshinobu Shiomori racing the YZF400 (1988)

Toshinobu Shiomori competed in the All Japan TT-F3 (Formula 3) road racing class championship riding the YZF400 factory machine based on the FZR400. In his 3rd year competing in this class, he took the 1988 title.

Struggling with the Question of Quick Handling

“Yamaha was a latecomer to the racer replica category, so it was a very bold decision to adopt the concept of developing a production model that was essentially a racer, and go on an all-out offensive,” says Jiro Izaki, a key member of the development testing group (Yamaha’s Road Testing Unit, 2nd Project Engineering Division at the time of the interview).

However, Izaki never expected that this would force a decision about whether or not Yamaha should continue its signature approach to machine handling that it had maintained until then.

“Even when we were developing our early racer replica models, we still believed 100% in our traditional Yamaha approach that being able to ride with assurance was what allowed a rider to go faster,” confides Izaki. “We believed that this was the same with race machines. When it was decided that we would be designing a racer, we thought we should first try riding an actual race bike, so we test-rode the TZ250. But, I found the ride to be quite different from what I had expected,” he adds.

“Until then, the racer group would take a production model we’d finished developing and then develop it further into a racing machine,” continues Izaki. “But the riders who raced on the YZR machines would say that, in the end, a production model can never become a purebred race machine. Looking back, it seems only natural that a GP machine developed primarily for cornering performance would have a different feeling from a production model. But at the time, this was a rather shocking revelation for us. So, those of us who were working on the FZR400 development project, with its aim of creating a model that could basically become an F3 racer as it was, had a very strong awareness that we were out to develop a race machine. It would be true to say that we had begun to feel that if we were going to succeed in this project, we might have to discard all the ideas that had guided us in our development of production models until then.”

The latest replica models from Yamaha’s rivals all had very quick handling characteristics. It was this kind of agile handling in their rivals’ machines that Izaki and his fellow testing group members had felt negatively about until then, but now they were seriously debating about whether or not they should accept this and other aspects as new standards.

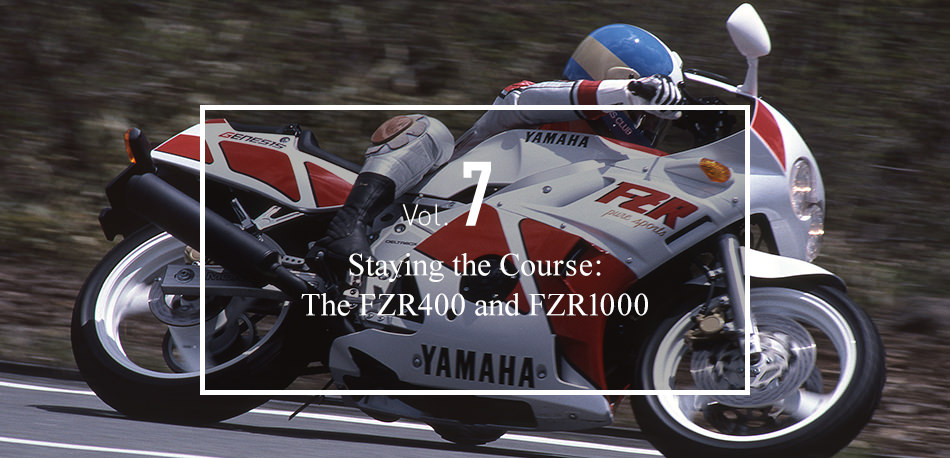

FZR400 (Released in 1986)

While it was developed to be a capable race machine, Yamaha did not like the quick and sharp handling characteristics typical of other manufacturers’ racer replicas, and instead chose to make the FZR400 a bike that was fun to ride on public roads.

“Even if we were going to change our premise that stability be a top priority, there was still a feeling of responsibility to achieve our goals,” says Izaki. “But, no matter how many times we test-rode rival machines, the handling was just too light and quick for us to feel comfortable with. I just couldn’t enjoy riding them. We might get used to it riding where we knew what was waiting on the other side of a corner, like on a test track, but it wasn’t a ride that we could enjoy on winding public roads where the conditions always vary, and that fact bothered us. Our final decision was that we would aim for a feeling of lightness, but we would make every effort to avoid anything that made the bike’s handling difficult for the rider to get used to.

“In the bike reviews of motorcycle magazines back then, there were cases where they rated a machine’s handling as good, but when we test-rode it, we just didn’t agree.

“Still, there were some people on the team who argued that if this kind of really quick handling was what the market wanted, maybe it was us who needed to change our way of thinking,” Izaki added.

You could certainly say that there was bias in the evaluation standards back then. In order to take into consideration the standards that the manufacturers were applying in their replica development, the motorcycles magazines were doing more of the test riding for their review articles on circuits and most of the evaluations in those articles reflected the performance potential they felt on the track. At RIDERS CLUB, we rejected this approach and continued to test and review replica models on twisty public roads where the customers would actually be riding and enjoying them. Still, we couldn't help being delightfully surprised at the light and sharp handling those replica models often had.

However, one of the things I always find difficult about test-ride reports for a new bike is avoiding the habit of letting your own personal riding style and whether or not it suits the model you’re testing influence the evaluation. To prevent that kind of bias, I make it a point to first try to get used to the model being tested, and then ride it in a way that makes the most of its strong points. This is something that varies with the rider’s career, experience and perceptiveness. For example, depending on the radius of the curve and the speed that you enter it, you have to adjust how quickly you lean the machine over in order to bring out well-balanced steering characteristics. This is normal. You can’t possibly get the same handling leaning in the same way for a 30 km/h hairpin turn and an 80 km/h corner. So, you find the right amount of lean that brings out well-balanced steering characteristics for the particular bike you are testing, and then give it good points if it performs well in that context. Of course, during an evaluation, I don’t let differences in riding experience and perceptiveness determine how well a bike performs.

But, from the standpoint of a manufacturer that has to design bikes for a wide variety of riders, the ideal is to get the bike’s handling to feel the same in any corner or turn. When manufacturers test a bike, they have to look for negative aspects [and fix them] without creating weak points. In this sense, you can say that a manufacturer’s own tests are stricter than ours. This is especially true when it comes to evaluating rival machines. In fact, we often have manufacturer test riders asking us if we really thought the bike was as good as we claimed it was in our reviews. Of course, this isn’t a case of them contesting our evaluation. It’s their professional concern that led them to ask us, because our review was quite different from theirs.

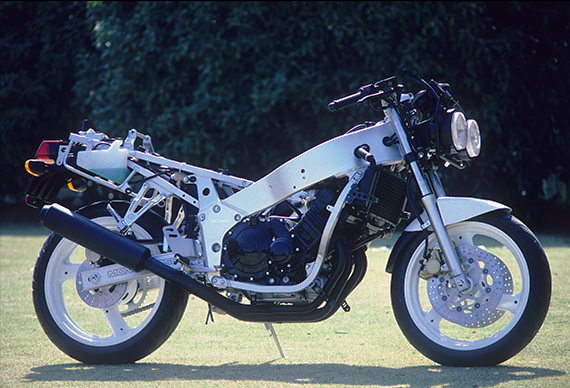

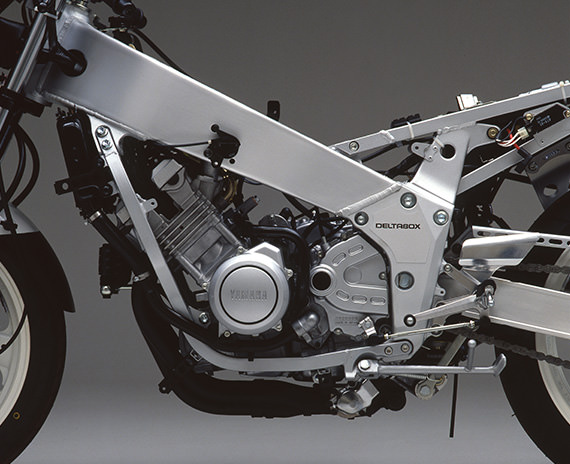

Employing a Radial Tire with a Revolutionary 60% Profile

“In line with the development concept of creating the FZR400 as a racer, it was decided from the beginning that we would be using an aluminum frame. This starting point already made the development approach different from our usual process. We would typically start by working out the frame layout based on the factors of what kind of rigidity and what kind of character we wanted the bike to have,” noted Izaki. “Since our factory machine had an aluminum Deltabox frame, we could rely on feedback from that. So, we had no second thoughts about what kind of frame we should use. Since the other manufacturers were using frames constructed with extruded aluminum, it might have been common course for us to explore that method as well, but because of our development concept to build a racer, the aluminum Deltabox frame was a must. Of course, there were other reasons contributing to this choice; we had a lot of development data from our race machines and being able to use that for developing things like rigidity balance with certainty was a big advantage.”

FZR400 (Released in 1986)

Based on the “Genesis” concept, the FZR400 featured an aluminum Deltabox frame mounting a liquid-cooled, 4-stroke, in-line 4-cylinder engine with a 45° forward-inclined cylinder block. It came equipped with low-profile radial tires.

The FZR400 was composed of Yamaha’s latest features like the "Genesis" concept forward-inclined 4-cylinder engine, and that gave the bike a form that was truly that of a racing machine rather than a replica. There was also another major statement that would be made in the FZR400: the adoption of a low-profile radial tire. “We had used a radial tire on a mass-production model for the first time with the XJ750D,” Izaki said. “It was mostly just a strong determination to use a radial tire for the first time, and it was simply a matter of making a tire of the same size but with a radial structure. As you know [Nemoto-san], a tire with that kind of profile doesn’t really bring out the advantages of the radial format.”

The difference between a radial tire and the conventional bias tire is in its structure. The internal structure of a tire has a “carcass” built around a base of synthetic fiber cords. However, these cords are not woven like those for clothing fabric, because if they were, the constant contortions of a tire subjected to load forces in motion would cause friction between the overlapping cords in the weave that would eventually sever them. So, the cords in a tire carcass run parallel in the same direction to each other and are joined together using special rubber. The cords in bias tires run parallel to each other but are set in diagonally offset layers across the entire tire. Adjusting the angle of this offset is how the necessary strength of the tire is achieved.

A radial tire differs in that the cords in the carcass are laid in the lateral direction (90° angle to the center of tire tread, i.e. “radial” from the center of the tire), and bound over with specially constructed reinforcement belts laid in the direction of tire rotation. This construction gives the tire both sufficient strength and flexibility to maintain contact with the road surface, even when subjected to heavier loads. A radial tire of course also has the merits of a higher grip threshold and less tire wear due to friction. However, in the case of a motorcycle which can be leaned over unlike a car, the sidewall portion of the tire needs to be shortened as much as possible in order to take advantage of the radial structure. Furthermore, if the tire is designed with a wide tread, it becomes necessary for the wheel rims to also be nearly as wide as the tread because of the shortened sidewalls.

This caused a conflict for the motorcycle manufacturers. They wanted to have the merits of the radial tire, but they were also hesitant to adopt an extremely wide 4-inch wheel rim for 400cc class machines, which used a 2.5–3-inch rim as standard. Their resistance was due to the fact that such a wide rim would make it virtually impossible for owners to replace their radial tires with conventional bias tires of the same size later if they wanted to. This factor put a brake on the full-scale adoption of radial tires for motorcycles and prevented a more effective radial design for the ones that were adopted.

Jiro Izaki, a member of Yamaha’s Road Testing Unit, 2nd Project Engineering Division at the time of the interview

However, Yamaha’s goal was to make the FZR400 a bike with performance that would leave their rivals behind. So they didn’t hesitate to mount it with the same type of wide tires used on the race scene, as well as choosing advanced radial tires to do so. In this way, Yamaha pioneered the practical use of the first “low-profile” radial tire (the section height of the tire was 60% of the section width of the tire) that has come into common use today. “Of course, we developed that tire jointly with the tire manufacturer,” says Izaki. “At first however, it certainly wasn’t something that could be ridden with. What’s more, its problems were attributed to the fact that it was a radial tire. I remember becoming adamant about it, saying ‘We can’t possibly put tires like these on a bike for customers!’ The tire manufacturer was also being more cautious than was probably necessary, saying that because they were radial tires, the chassis and suspensions had to be specially designed to accommodate them.”

These were the first full-fledged radial tires for a motorcycle. The tire manufacturers had already overcome challenges to make radial tires a new standard for cars. They had encountered a series of fundamental difficulties; equipping a car with a conventional suspension with steel-cord radial tires—boasting great stability and grip—made the car come close to rolling over when turned sharply during development tests. This led to an interim measure of using synthetic textile cord in place of steel belts to scale back the performance benefits of radial tires until the automakers could develop their chassis and suspensions to fully handle them. The excessive concern from these experiences meant the tire manufacturers expected that radial tires would change everything about motorcycle construction as well.

In actuality, however, it wasn’t necessary to go that far. The simpler they made the combination of wide wheel rims with a very flat, low-profile tire structure, the easier it was to eliminate the problems and bring out the excellent benefits of radial tires. “Being a new endeavor, our being too cautious probably ended up with us actually wasting a good amount of time and effort in the development process. For example, we could have reduced the rigidity even more, but we couldn’t be so adventurous. Because of this, most of our time and effort involved in developing the handling of the FZR400 was spent on practicalizing the low-profile radial tire.

“Despite all these efforts and difficulties, once the FZR400 was released, our rivals didn’t counter with models of their own with this size of radial tire for some time. I was shocked by this [lack of] response, after all the effort we had made knowing that if we were going to do it, we had to make it ‘the real thing’ that brought out 100% of the benefits of radial tires. There were people in the company who wondered if all of that effort had been worth it, and some even said, ‘Look, now everybody thinks Yamaha’s making a big deal out of nothing...you’ve gone too far.’”

Still, after this, a 60% profile would become the new standard size of radial tires for motorcycles, and as everyone knows, the other manufacturers would eventually follow suit with most of their supersport models, and use this kind of tire to this day.

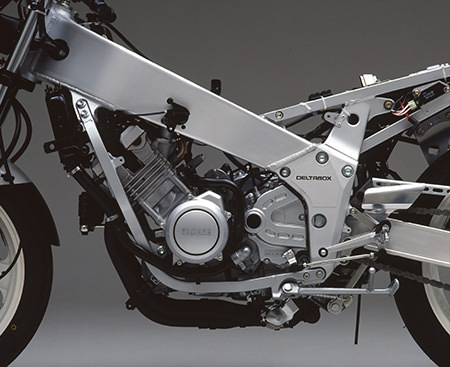

The aluminum Deltabox frame and forward-inclined engine

Yamaha’s aluminum Deltabox frame was developed based on technological feedback from the racing arena, and it mounted an engine with a forward-inclined cylinder block. This combination enabled a downdraft design for straight intake/exhaust flow and a low center of gravity at the same time.

The Ride Has to Be Fun

After successfully fitting the FZR400 with the first full-fledged motorcycle radial tire, the model entered its final stage of development. Izaki comments: “Right down to the very end, we had heated arguments over and over about the bike’s feeling of lightness. Compared to the almost feathery lightness of our rivals’ models, some people in the company were saying that ours wasn’t sharp enough and that the response was dull or heavy, and the fact that they weren’t used to the great stability that the radial tires provided only compounded such responses. Although we weren’t as fixated on stability as usual, we still weren’t willing to compromise on our determination to ensure that the bike feel reassuring to the rider.”

Compared to other Yamaha bikes until then, the FZR400 that was released on the market was actually lighter in handling and more agile at times like when beginning to lean into a turn. But they hadn’t given it the kind of quick handling that the rival machines had, so it somehow felt like it had a more stable and composed ride character. Furthermore—although it‘s hard to include this as part of an evaluation of a bike’s handling—the benefits of the radial tires were very palpable, such as the feeling of stability during cornering akin to a big bike, and the awesome braking performance that still felt very stable.

FZR400R (Released in 1987)

Only 2,500 of these were produced and sold, as a base for developing a racing machine. It had specs like a single seat and footpegs positioned 40 mm rearward to make it immediately eligible for All Japan TT-F3 (Formula 3) races.

“We also used suspension settings with a deeper compression stroke and longer rebound stroke that made the ride feel soft. This was another thing that people in the company were saying wasn’t ‘sporty’ and that the bike didn’t feel like a racer replica. But, it had a feeling of stability and was easier to control, and even if the tire did slip, the longer rebound slowed the motion and gave the rider more time to make a recovery. That’s why we can’t rashly decide to give a bike settings that make the suspension too hard,” concluded Izaki.

Back then when tire grip—a big factor influencing riding ease and control—had dramatically improved [with radial tires, etc.], it was probably becoming difficult to find a clear performance difference using just the suspension settings when testing was done on a full-on circuit. But if we take World GP riders as an example, the ones who are really championship contenders will typically choose suspension settings that give a longer rebound stroke but the lowest possible setting for damping. This is because World GP riders have the skills to react to something happening due to the soft suspension settings, but they have to depend on the suspension when recovering [from wheel slipping and the like] when riding near a bike’s performance limit. This was a conclusion reached by veteran racers that rode under some of the toughest racing conditions.

While the FZR400R used the same engine as the FZR400, it boasted lightened pistons, an added friction plate for the clutch, a close-ratio transmission with the same spec as the one supplied in the All Japan TT-F3 (Formula 3) racing kit and more.

“It’s a fact that we were unable to establish a clear advantage over our rivals on the track. But when you took the FZR400 out on winding roads, its handling as well as its engine character, made it very fast. As far as we were concerned, we had done what we’d set out to do,” said Izaki. “Looking back now, the market and the manufacturers were both leaning in the same direction at the time. Even we were running tests using racing slicks since we knew from the development stage that the FZR400 was going to be used in racing. But now, I believe that it would have been wrong to develop a product that we would have to tell users, ‘It’s actually a bike that’s most fun to ride on the circuit.’

“Even though we’d always believed that we had to develop bikes that were fun to ride, I think everyone was suddenly starting to get carried away with a bike’s ‘image’ instead. I felt that the whole motorcycle world was getting lost in admiration of scenes of dragging your knee on the pavement when cornering. But, I also knew if that was all we offered them, the users would eventually start to shy away from such products,” recalls Izaki.

This realization would soon have a big influence on the direction Yamaha would take in its big-bike development. I think managing to defend its tradition of handling that let you ride with a sense of assurance even through the peak years of the replica boom gave Yamaha a strong aura of independence that set it apart from its competitors. In that sense, the struggle that Yamaha went through as one of the manufacturers involved in the racer replica era would eventually be very meaningful for the company, and they would emerge from it with a new direction aimed toward not only a feeling of stability in the ride but also a strong dose of fun for the person riding it.

(Continue to Part 2)