Struggles with the TX750 and TX500 Bring a Return to the TX650

Having achieved levels of performance comparable to the British bikes but falling short of the 4-cylinder models of the other Japanese manufacturers, Yamaha would go on to introduce the TX750 and TX500 models in 1972 and 1973, again with the twin-cylinder engine but seeking higher levels of power.

The TX750 was capable of speeds up to 200 km/h and adopted a double cradle frame.

These two models were destined for unexpectedly short product lives, however. The main reasons were a problem with heat build-up that prevented stable engine performance and insufficient machine durability, both fundamental flaws for the type of high-speed long-distance riding common in overseas markets but not in Japan. This forced Yamaha to give up the prospect of exporting the two models. While other manufacturers were still content as long as they didn’t get complaints from the American market where speeds were not as high in regular use, at this point Yamaha had already taken its models to be tested in the more severe European market. “That was the first time we went to Europe to test. The test riders over there believed that you should run the machine until it breaks down, and only then can you really evaluate it, so they just kept running the machine as hard as they could. As for us, we had a pretty good idea at what point it would break down, so we couldn’t do things like that. We were even asked by the Japanese Yamaha staff working in Europe if we could even ride as much and as hard as those test riders!”

Eventually, although some lots of the TX750 and TX500 were delivered to Europe, they didn’t succeed in getting good reviews for durability and handling and things ended with virtually no prospect of Yamaha’s 4-stroke big bikes being successful in the European market.

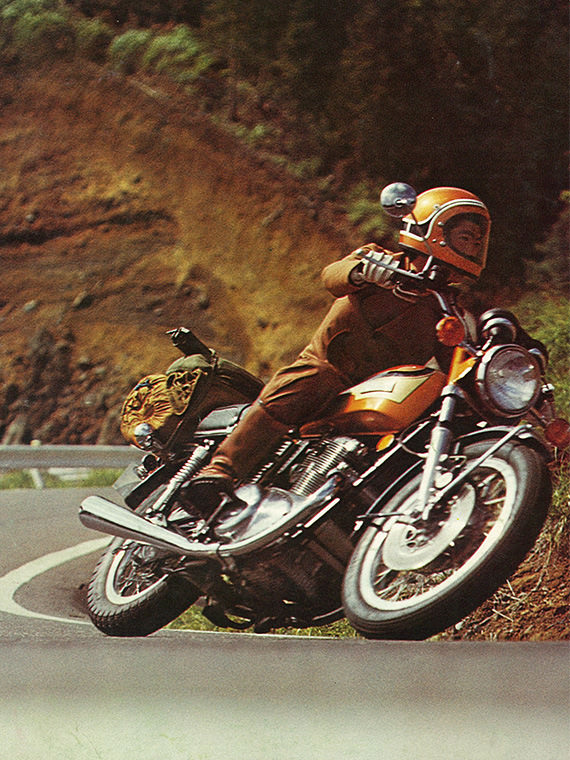

Advertisement photo for the 1972 TX750

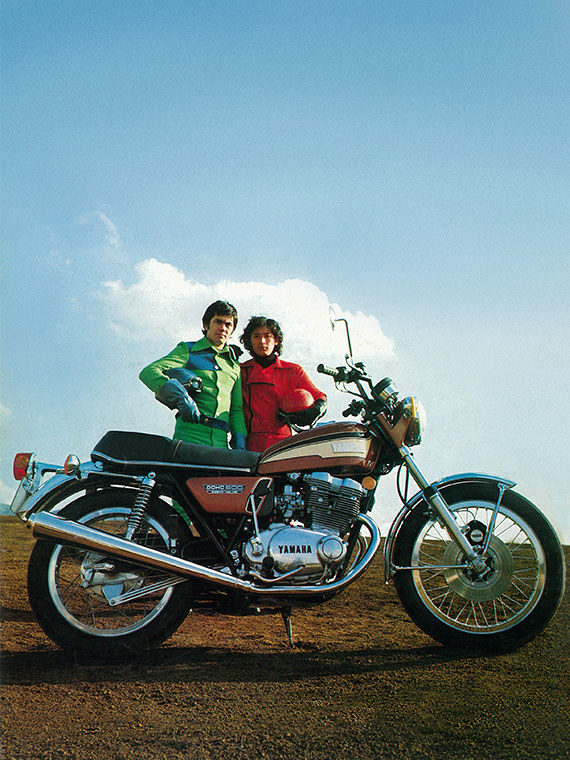

Advertisement photo for the 1973 TX500

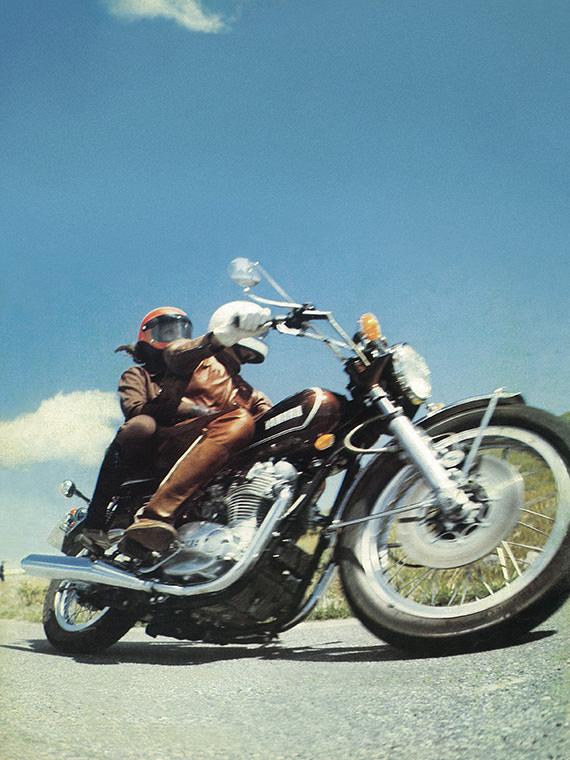

Advertisement photo for the 1973 TX650

With the TX650, however, although it was similarly judged as lacking high handling performance, there was no real problem in the area of durability, so it was decided to continue the model while working on further maturation. According to Mr. Fujimori,

“In America, we had to deal with the rain grooves* in the roads on the West Coast, so we worked together with the tire manufacturer and in other ways to solve the issue. Thanks to the long product life of the 650, we were able to learn quite a lot over the years. For example, through trial and error to fix the speed wobble problem at the swingarm pivot, we found that stacking three gusset plates there provided the best balance that wasn’t too stiff and didn’t wobble much.”

Concerning the evolution of the swingarm pivot from a simple steel plate on the original XS-1 to what you would call the “box” construction with the highly rigid appearance it eventually acquired, we learned about the following episode representative of the development team’s struggles. “In the case of reinforcing the swingarm, we learned what happened when it was positioned closer to the pivot and what happened when it was closer to the rear wheel. In short, working on the 650 became a course in the know-how of fundamental chassis design. It was a model that I will never forget.” As for myself, I was also a test rider for a tire manufacturer at the time, and I too have a lot of memories regarding the TX650, from the handlebar speed wobble tests to the road tests in Europe. That’s because, until the subsequent appearance of the 3-cylinder 750cc model, the 650 was a bike that left an important footprint in the quest for handling performance.

(Continues in Vol. 4)

*Rain grooves are thin grooves cut longitudinally into the road pavement as a means to improve water runoff and help prevent hydroplaning by vehicles when continued heavy rainfall would otherwise leave a dangerous layer of water on the road. In the case of motorcycles, however, these longitudinal grooves have a greater tendency to catch the tires and often cause the rider to panic. This problem led to the need for tires less susceptible to the effects of these longitudinal grooves.