Challenges Carving Our Name into Racing History

From 500s to MotoGP: Developing Machines to Surpass Rider Expectations

In 2002, the year that the world’s premier motorcycle road racing championship was rebranded as MotoGP, Yamaha entered the 4-stroke YZR-M1 as its factory contender for the new era. Italian racer Massimiliano “Max” Biaggi took several podiums and won the Czech GP and Malaysian GP later on that year, but over the course of the season, the gap with Yamaha’s rivals became increasingly evident.

The turning point at which the M1 and Yamaha began transforming into a force at the front of the grid came when Valentino Rossi joined the team in January 2004. At the time, engineers offered him four engine combinations to test, using either the current 180° flatplane crankshaft or a 90° crossplane crankshaft and with either four or five valves per cylinder. Rossi chose the crossplane crankshaft with the 4-valve configuration, just as Yamaha’s engineers had predicted. This moment marked the beginning of Yamaha’s journey to glory and firm presence at the front in the new MotoGP era.

Matching the M1 to the tires used in the series presented numerous trials and tribulations for Yamaha as well. In 2008, the Fiat Yamaha Team was composed of Rossi and class rookie Jorge Lorenzo, but the two riders used different tire brands, with the Italian running Bridgestones while the Spaniard was on Michelin rubber. Yamaha had elected to take the unprecedented approach of providing two riders within the same team with two different makes of tire.

Yamaha had welcomed the challenge out of respect for the wishes of its riders, striving to offer them competitive machinery that exceeded their expectations, and took demonstrative steps to that end in the 2000s.

The YZR’s Potential Seen in 2000

The defining points of a season can sometimes be uncovered by looking at its opening and closing rounds. This was certainly the case in the 2000 500cc World Championship season. The opening round in South Africa saw Aussie Garry McCoy take his maiden 500cc win, displaying a fantastic riding style by backing his YZR500 in on corner entry. Meanwhile in the 250cc class, the title contest went down to the final lap of the final round between teammates Olivier Jacque and Shinya Nakano. The conclusion to the epic showdown for the championship between the French and the Japanese rider was anybody’s guess right to the finish line, with the two YZR250s crossing it neck and neck. The season ushering in the new millennium was one that once again demonstrated the incredible potential of the YZR in both classes.

McCoy secured a seat on the Red Bull Yamaha WCM team in the middle of the 1999 season, and once he had gotten accustomed to the YZR500, he took a 3rd place podium finish at Round 12 in Valencia. The following year, he contested the full season with the team and amazed fans right from the start with his breathtaking riding style at the aforementioned South African GP season-opener. Getting his machine sideways and sliding the rear to shift direction on corner entry, he was able to best fellow YZR500-mounted Carlos Checa and Honda’s Loris Capirossi to take the win in Welkom.

In following racing, interest typically gathers around who is likely to win the next round, but the 500cc season that year was a different story; McCoy’s style had captured fans’ hearts. When one wildcard rider followed McCoy around the track and observed him during qualifying practice, his comments on McCoy’s riding style became the talk of the paddock. “Sliding around the track like that will only burn up his tires, so he’ll only be at the front for the first few laps,” was the word that went around, but McCoy rode on, style unchanged.

From Round 3 onward, he was constantly plagued by inclement weather that made tire choice difficult for him and his results faded, but the Aussie returned to winning form at Round 12 in Portugal and Round 13 in Valencia. Of the YZR500 riders that year, McCoy finished highest in the points in 5th overall with three wins to his name. Besides McCoy, YZR500s were entrusted to Japanese racer Norifumi “Norick” Abe, Italy’s Max Biaggi, Carlos Checa from Spain, and Frenchman Regis Laconi. With each one using a different riding style, their setup demands were equally varied and it was a season in which the YZR500 showcased its adaptability.

Meanwhile, in the 250cc class, the YZR250 stood alone in the spotlight at the final round of the season. Yamaha began entering a factory YZR250 in the class in 1986, taking the title the same year with Venezuelan rider Carlos Lavado and doing it again in 1990 with American racer John Kocinski. In 1993, Japanese rider Tetsuya Harada rode the TZ250M to a title win but following that, Yamaha largely fell out of title contention in the 250cc class.

It was in 1999 that Yamaha introduced an all-new YZR250 with the goal of recapturing the title and the Chesterfield Yamaha Tech3 team paired Olivier Jacque with Shinya Nakano. In their first year of competing, Nakano won Round 2 in Japan while Jacque won the season finale in Argentina, but through the course of the season, they were often outclassed by Valentino Rossi on the Aprilia RS250. In their second year in 2000, the two had grown considerably and became the standout protagonists in the championship.

At the final round that year in Australia, a mere two points separated the two teammates—whoever won the race would be crowned world champion. Their dogfight for the lead lap after lap was a scintillating spectacle for the fans. On the long-awaited final lap, Nakano exited the final corner in the lead, but Jacque was in his slipstream for the drag race to the finish line and he nabbed the win by just 0.014 seconds. Although Jacque won the title, the incredible season-long battle between the two became one of the all-time greats of the 250cc class and is still talked about to this day.

Nakano used his skill at the handlebars to deftly steer his YZR250 through bends while Jacque would carve beautiful flowing lines through the corners. The YZR250 performed equally well with these two subtly different riding styles, and with the YZR500 as well, one could say that it was Yamaha’s “rider-first” development approach that led to close battles like this.

A Turning Point: January 2004 in Sepang

With MotoGP’s inception in 2002, 2-stroke 500cc bikes turned wheels in anger for the last time together on-track with the era’s new 4-stroke 990cc machines in the premier class. These 990cc 4-strokes were the standard until 2006 and over the course of those five years, a major turning point came for Yamaha in 2004. In the third season of the new MotoGP class, reigning MotoGP World Champion Valentino Rossi made a shock move to Yamaha from Honda. His talent for developing a bike as well as his skills in the saddle were instrumental in Yamaha winning back-to-back titles in 2004 and 2005. However, while the YZR-M1 made incredible forward strides, it was effectively blazing a trail into uncharted territory at the same time. If we retrace the footprints the machine made at the time, the trail leads us to just south of the equator at Sepang International Circuit in Malaysia. Rossi was eagerly awaiting his first ride on the bike on the final weekend of January 2004.

Winding back the clock a little bit further to 2002, Yamaha had entered its new YZR-M1 in the MotoGP class and Carlos Checa rode it to a 3rd place finish at the Japanese GP season-opener. Though the Yamaha contingent trailed the Hondas for much of the season, Max Biaggi took the M1’s first-ever victory by winning the Czech GP and followed it up with another win at the Malaysian GP. But for the most part that year, Yamaha was overwhelmed by the competition.

The following year in 2003, the M1 gained fuel injection but it still went winless. Brazilian Alex Barros took the sole podium finish for Yamaha that year with a 3rd place at the French GP. With this prolonged dearth of results, the M1 development team was desperately searching for a solution. “Looking back on those two years, the main reason we were losing out—based on a more scientific perspective—was that the drive force at the rear wheel lacked linear feel,” recalls one engineer. “In comparing and analyzing the performance of the V4s of our rivals with our inline-four, we came to realize that the biggest difference wasn’t the power output itself, but it was the quality of the power produced, or basically, the quality and characteristics of the engine’s torque.”

The YZR-M1’s basic construction consistently features a longitudinally compact inline four-cylinder engine. This is due to the merits it brings, such as a great deal of freedom for choosing a mounting position in the chassis, the ability to optimally load the front wheel, and ensuring excellent performance through corners. This was the focus when developing its now signature inline-four crossplane engine. A distinct difference between an inline engine and a V-engine is the phase of the crankpins. One unavoidable trait of reciprocating engines is that in order to minimize vibration as much as possible, there is a predetermined ideal phase depending on the number of cylinders and engine type. The ideal phase for an inline four-cylinder powerplant is 180° while it is 90° for a V4 due to it being the ideal V-angle between the front and rear cylinder banks.

Another unavoidable characteristic is that the rotational speed of the crank fluctuates slightly over the course of one revolution due to the inertial force of the pistons and other components. In a typical inline-four engine, the crankpins are arranged in a 180° phase between the outside two cylinders and inside two cylinders in a flatplane configuration, so when the four pistons line up at their respective top dead center and bottom dead center, the secondary forces increase by a factor of four.

With a crossplane crankshaft, the crankpins are arranged in a 90° phase between the left two and right two cylinders, which cancels out this variation in rotational speed.

With a flatplane 180° crankshaft, the inertial torque is larger than the combustion torque. On the other hand, what Yamaha’s engineers trained their eyes on was the fact that the inertial torque of a crossplane 90° crankshaft can be minimized to the point of being inconsequential compared to the combustion torque. This is the “quality” the engineer mentioned above.

Before the first day of pre-season testing on January 24, 2004, Rossi was taking a pragmatic approach: “It’s been a long time since I rode a bike, more than two months. And everything’s completely new, so it’s almost starting from zero. I’ll need one day just to get used to riding again, just to recalculate the speed and the braking. And the bike will feel different to what I have been used to.”

At the test, he tried and compared several types of engines. An engineer at the time spoke on what transpired at that year’s test: “We tested the same 180° crankshaft engine we’d been using and a new 90° crankshaft engine, with a four-valved and five-valved format produced for each. Of those, Rossi liked the 4-valved engine with the uneven firing order. He called it ‘sweet’ and by that I think he meant that it felt very predictable with a gradual response that made it easy to control. That was also the variation we had expected to do well.

“Employing an uneven firing order also wasn’t our original goal. We wanted to minimize inertial torque as much as possible and chose the crossplane crankshaft to do it. The firing order became uneven in order to make that happen, that’s all.”

The opening round of the 2004 season in South Africa saw Rossi battle it out with the now-Honda-mounted Biaggi before emerging the victor. It was a breakthrough that led to Rossi taking a season-topping nine wins and Yamaha claiming its first premier-class title in 12 years. The decisions and developments that year led to subsequent advancements with the M1 and Rossi would later go on to cement his position as the biggest star of MotoGP.

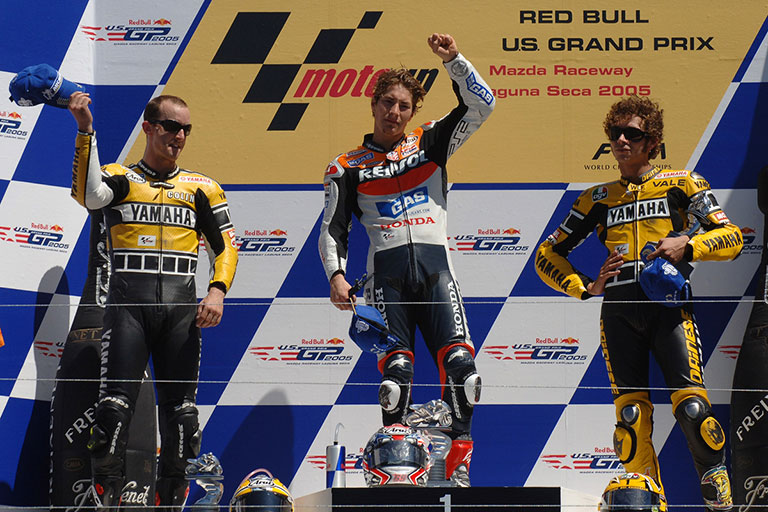

In his second year with Yamaha in 2005, the Italian’s momentum had not waned in the slightest; he had never finished off the podium and had already secured six wins by the time the MotoGP circus made its way to Laguna Seca for the first US GP in 11 years. There, Rossi and his American teammate Colin Edwards raced with a special commemorative yellow/black livery and they both finished on the podium. Harking back to the 1970s era of Grand Prix racing with modern MotoGP machines made for a special atmosphere and was a gesture of gratitude from Yamaha to the fans. Of the 17 rounds on the calendar that year, Rossi won 11 of them and not only took a second consecutive title for Yamaha but also secured the Triple Crown by winning the Team and Constructor titles in the process.

“Back then, we were aiming for characteristics that would deliver very linear throttle response. The ultimate ideal is to provide the kind of torque you get with an electric motor,” says one engineer who was involved with the M1’s development at the time. Over 15 years have passed since that pivotal decision in Sepang in January 2004, but the YZR-M1 continues to evolve and improve driven by such ideals.

Another Turning Point: May 2008 in Shanghai

In early May 2008, it was a holiday weekend so there were fewer people on the streets of Shanghai, but some 20 kilometers northwest of the city center, the atmosphere at Shanghai International Circuit was lively. Would Rossi take his first win at the Grand Prix of China since his last three years ago in 2005? How would rookie sensation Jorge Lorenzo do around the track? He had already taken his first premier-class victory at the preceding round in Portugal. Under warm, sunny skies, the race got underway and Rossi held off Honda’s Dani Pedrosa and Ducati’s Casey Stoner to take his first win of the season, marking the first top-step finish for a YZR-M1 on Bridgestone tires.

With the momentum gained from notching this win, Rossi got into fierce battles with Stoner throughout the season and won nine GPs to secure the title, returning to world champion status after missing out to Nicky Hayden in 2006 and Stoner in ‘07. But the road to that Shanghai win had been a tough one. When MotoGP’s rules switched to a maximum displacement of 800cc in 2007, Yamaha had prioritized fuel consumption and ridability in development and in turn lost out to its rivals in top speed. This produced several races in which the M1 was not living up to rider expectations.

To address this, the team worked to increase the engine’s maximum rpm. The intake and exhaust valves initially used traditional spring technology that year but were later upgraded to pneumatic valves as Yamaha gradually upped the unit’s performance across seven engine updates, slowly closing the top speed gap. As this was happening, Rossi did his best to take four wins on Michelin tires, but lost out to the Bridgestone-shod Stoner for the 2007 title. Near the end of that season, Rossi and Yamaha came to the decision to also run Bridgestones instead the next year.

In the 500cc era, engineers would say, “If we don’t first decide on which tires the bike will run, we can’t even get started on developing the bike.” But in 1987, Team Lucky Strike Roberts used Dunlops while the Yamaha Marlboro Team were on Michelins. Each team ran their own searches for how to best extract performance from each tire and the result was Mamola taking three wins for Lucky Strike Roberts and Lawson securing five for Yamaha Marlboro, finishing 2nd and 3rd in the championship, respectively.

However, that was with two separate teams; to have two riders in the same team select two different tire makes had never been done before. Rossi had elected to run Bridgestones while Lorenzo chose Michelins—this was a new challenge for Yamaha. They were teammates in the Fiat Yamaha Team, but in order to facilitate the use of both brands within the same team while ensuring data confidentiality, Yamaha organized separate rider pit boxes while operating and racing as one team. According to the team staff from the time, this effectively removed the technical confidentiality concerns the two tire manufacturers had while greatly aiding in keeping each rider and their team staff focused on the tasks at hand. The success of this system was clear as Rossi was able to take the first of his nine wins that season in China, sending him on his way to recapturing the title in 2008.

Due to a change in the rules the following year, Bridgestone became the sole tire supplier to MotoGP, but the Fiat Yamaha Team continued with its one rider, one pit system. Rossi clinched a second consecutive title with six victories while Lorenzo won four races of his own and finished as the championship runner-up, giving Yamaha and the YZR-M1 the top two spots for the season.

The Fiat Yamaha Team retained its two riders for the 2010 season, but an injury he sustained in a crash during practice at Round 4 took Rossi out for four consecutive rounds. On the other side of the Yamaha garage, Lorenzo had never finished lower than 4th and had taken seven wins before coming to Round 15 in Malaysia. His 3rd place podium finish there was enough to secure him his first MotoGP World Championship title with three races left to go and this also marked the third-straight MotoGP Triple Crown for Yamaha. The man in the center of that momentous achievement was a stark departure from the young rookie in China two and a half years prior whose injury from a high side in practice drastically affected his race. Lorenzo’s championship win in just his third year in MotoGP is inextricably linked to Yamaha’s one rider, one pit system of the time.

In 2004, the inline-four crossplane crankshaft engine that Rossi chose in Sepang from among the four engine variations prepared had its performance augmented in preparation for the opening round of the season in South Africa. It not only powered him to the win at his first race on a Yamaha there at Welkom but also to the MotoGP title that year and the next. Rossi won the championship again in 2008, thanks in part to Yamaha’s efforts to understand the engineering ideals built into the Bridgestone tires he used and conducting extensive engine tuning to extract maximize performance from them. The buildup of data and knowledge acquired contributed to the Italian securing another back-to-back championship in 2009 and Lorenzo’s first championship in 2010, giving Yamaha the premier-class Triple Crown three years in a row. Yamaha’s policy of respecting the ideals of its riders and philosophies of its official suppliers has been steadfast for generations, and this approach is intrinsically linked to the company’s Monozukuri spirit of excellent quality and craftsmanship that strives to exceed riders’ expectations.

Top