Challenges Carving Our Name into Racing History

Yamaha’s First Premier-Class Title a Long Time in the Making

Honda and Suzuki withdrew from Grand Prix racing at the end of the 1967 season. After Yamaha dominated the 125 and 250cc classes the following year, it also suspended its factory effort in GPs. However, Yamaha maintained a presence in the series throughout this period by developing and offering production road racers that several privateer teams and riders used to win numerous titles.

In 1973, Yamaha returned to the Grand Prix paddock as a factory team and began competing in the premier 500cc class, winning the Constructor title in its second year. All the while, Yamaha cultivated a spirit for racing, rising to answer the passion of its racers and prioritizing their needs while promoting technological development. This spirit was the driving force behind the team’s 500cc class campaigns and the birth of Yamaha champions like Giacomo Agostini and Kenny Roberts.

Daytona Beach and Paul Ricard

The gorgeous shores of Daytona Beach in Florida, USA, boast sand comfortable for barefoot strolls, but the beaches of this Atlantic coastal city have also played host to motorcycle races in the past, with Norton and Harley-Davidson machines racing around oval tracks carved into that sand. And some 7 kilometers from the beachfront lies the legendary Daytona International Speedway.

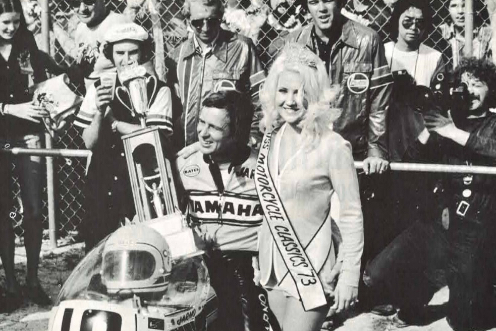

On March 11, 1973, it was a hot and humid day not very different from midsummer in Japan. Yamaha was competing in the Daytona 200, which unofficially kicked off the world’s motorsports season. It was the preamble for the Yamaha factory team’s long-awaited return to the Road Racing World Championship Grand Prix after a five-year hiatus. Finnish rider and 1972 250cc World Champion Jarno Saarinen rode a prototype TZ350 production racer to win the race, beating 750cc machines on his way to the checkers. It was a great show of force in preparation for the 500cc GP campaign.

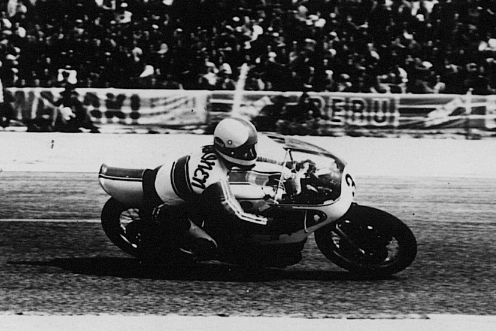

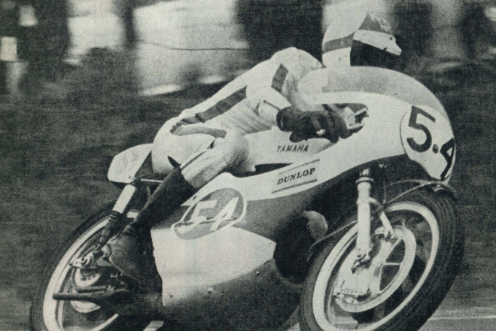

The 500cc YZR500 (0W20) was finally ready and was in the Paul Ricard Circuit paddock on April 22 for the venue’s first Grand Prix event. Lining up alongside Saarinen was his teammate, 1971 All Japan Champion Hideo Kanaya. Their chief rivals were British rider Phil Read and Italian legend Giacomo Agostini on the 4-stroke, 3-cylinder MV Agusta, with the marque aiming to capture its seventh consecutive championship. Unperturbed by such fearsome rivals, Saarinen scored a debut 500cc class win for himself and for Yamaha, with Kanaya also finishing on the podium in 3rd. In the next round in Austria, they took a 1-2 finish in what was a solid first step towards Yamaha’s long and successful career at the pinnacle of the sport.

While Yamaha’s factory racing efforts had been put on hold, this did not mean Yamaha itself was resting on its laurels. For the four seasons beginning in 1969, the company focused on producing and selling production racers like the 350cc TR-2 and 250cc TD-2. At that year’s West Germany GP, Swedish rider Kent Andersson rode a TD-2 to take Grand Prix’s first-ever victory on a production racer. These machines found their way onto grids in GPs and other championships around the world.

British racers Rodney Gould and Phil Read rode production TD-2s to win successive 250cc Grand Prix titles in 1970 and 1971, respectively. At that time, the TD-2 dominated the top of the class rankings, with 10 of the top 20 riders of 1969 on TDs, 15 in 1970, and 18 in 1971. While the TD was originally developed for amateur racing, it had become the undisputed number one mount to have in the world’s top racing series.

While development of these production racers continued, Yamaha was also simultaneously developing its first factory YZR500 for Grand Prix’s 500cc class and a 700cc machine meant for the Daytona 200. To ensure development efficiency and technical reliability with the machines, two 2-cylinder engines from the 250cc TD-2 and two from the 350cc TR-2 were lined up and coupled to form in-line 4-cylinder power units, one at 500cc and one at 700cc. The knowledge Yamaha had gained through building production racers was put to full use in creating these two new 4-cylinder mills.

Then in 1972, the FIM created the new Formula 750 (F750) racing class, and in 1973 it became a new standalone series run on a separate calendar from the Grand Prix World Championship. Race fans were excited about the future in store with this new F750 class.

A Decisive Choice to Secure the 500cc World Champion’s Services

In 1973, Yamaha had gotten off to a strong start in the opening stages of the World Championship, but a major on-track incident at Round 4 in Italy changed everything. During the 250cc race, Saarinen was involved in a massive multi-bike crash on the first lap and sadly lost his life. In mourning, Yamaha canceled its factory effort for the rest of the year.

Around the same time, there was an upheaval in the global economy. One U.S. dollar had been worth 308 yen in the fixed exchange rate system established by the Smithsonian Agreement, but in February 1973, Japan changed to a floating exchange rate regime, a development the country’s export industry found difficult to swallow. In October that same year, Japan was hit by the first oil crisis, triggered by the embargo instituted by Middle Eastern oil producers. The ensuing spike in oil prices plunged the global economy into a dark period with no foreseeable end.

But even as this was happening, Yamaha’s fiery passion for racing remained. In December 1973, Italian racing hero and seven-time 500cc World Champion Giacomo Agostini joined the Yamaha factory team. Upon announcing his signing, then-company director Hideto Eguchi calmly said, “The situation around the world is indeed dire, but Yamaha is about growing the world of motorsport and we will keep to the same stance we’ve always had. Racing is a great way to quickly improve on our technological achievements, and no matter what the situation is, we want to continue our quest for new technologies. Signing Agostini is a display of our desire to carry on with both motorsports and technological development.”

Then in 1974, Agostini made his debut for Yamaha in March at the Daytona 200. Riding a just-finished TZ750 in his first-ever entry in the iconic race, he nonetheless won in convincing style. He took that momentum with him as the GP season began in Europe the following month, winning in Austria and the Netherlands. His Yamaha teammate Teuvo Länsivuori also won the Swedish GP in Anderstorp, and although it was Yamaha’s first full season of premier-class competition, it managed to not only win the 500cc Constructor title but also in the 125cc, 250cc and 350cc classes as well.

Agostini and Kanaya comprised the factory team the following year in 1975. Once again piloting the YZR500, they battled against Phil Read on the MV Agusta and the Suzukis of Länsivuori and British star Barry Sheene, with Agostini coming out on top to win the title. For Agostini, it was his first championship triumph since his 350cc title for MV Agusta in 1973 and Yamaha’s first 500cc premier-class Rider title.

Kanaya played a pivotal role in raising the competitiveness of the YZR500. He secured his first 500cc race victory in Austria, but as Agostini found his stride with back-to-back wins in West Germany and Italy, Kanaya withdrew from the championship and returned to Japan to focus on helping further sharpen the YZR500.

Many in the media felt that if he had instead kept competing, Kanaya would have been in with a chance of lifting the title, but Yamaha had him come back to Japan and work closely with the engineers and mechanics to support Agostini’s championship challenge in a show of teamwork embodying Yamaha’s racing spirit.

A Tale of Two Technologies

The Monocross single-shock suspension and Yamaha Power Valve System (YPVS) were major contributors to the performance of Yamaha’s factory racebikes in the 1970s. The former debuted on the 1974 YZR500, with the shock positioned below the fuel tank to allow for longer wheel travel and more mass centralization, resulting in more stable handling.

The latter was designed to improve 2-stroke engine performance. In 1977 at the Finland GP, Venezuela’s Johnny Cecotto rode the first YZR500 (0W35) with YPVS. The technology was refined and fitted to the YZR500 (0W35K) in 1978, on which “King” Kenny Roberts clinched his first of three successive 500cc titles (1978–1980), demonstrating the benefits of YPVS on the racetrack.

These two technologies were not conceived from the outset to improve the competitiveness of Yamaha’s racing machines. In fact, their origins lay in different disciplines altogether. The Monocross suspension came from the motocross world, while YPVS was born of research to address exhaust emissions and improve eco-friendliness. The Monocross suspension was the brainchild of Belgian engineering professor Lucien Tilkins. Yamaha purchased the patent for the design and built a monoshock to use in its motocross machines. The design was instrumental in Yamaha winning the 1973 250cc Motocross World Championship title with Hakan Andersson.

Of course, Yamaha did not reuse the shock from its factory motocross bike as-is. “While there are no structural differences from the motocross version, we did change the setup,” said engineer Makoto Sugiyama. “We needed a greater degree of fine tuning, so we added an adapter gear to adjust shock length, included damping force adjustability and the like. The riders praised the handling improvements thanks to the better cushioning performance and mass centralization the shock brought.”

YPVS was originally derived from research Yamaha was conducting into various means of meeting emissions regulations. The 1970 amendments to the Clean Air Act in the United States made regulations on exhaust emissions stricter, prompting many manufacturers to begin exhaust gas purification research. The exhaust gas of a 2-stroke engine contains about one-tenth the nitrous oxide of a 4-stroke engine, but since 2-stroke engines do not have intake and exhaust valves, the blow-by effect results in the gas containing much more hydrocarbons instead.

It was during efforts to solve this that YPVS was born. The system places a variable valve near the exhaust port that moves according to engine revs, providing the same power at high rpm, but also delivering strong pull at low and mid-range rpm. “YPVS was incredibly effective in terms of its benefits for road racing,” acknowledged one engineer. “We saw a two-second advantage while testing at the Yamaha test course.” Both of these technologies live on today and stand as shining examples of innovative Yamaha technologies that continue to progress even now.

The Glory and Sorrow in Three Straight GP Titles and

Yamaha’s Insurmountable Daytona 200 Streak

In light of the uncertainties with the global economy, Yamaha ceased all factory efforts outside Japan in 1976, but maintained a presence in GP paddock by supplying top riders with factory-spec machines through European importers, thereby keeping the excitement on the GP scene high. Yamaha also called on its relationships with the technicians and others involved in the series. A team manager at the time shared his perspective: “Unlike the ‘60s when our work was mostly done by Yamaha employees, back then in ‘75 and ‘76 we had more and more people involved with the teams like part vendors and sponsors. That broadened our perspective and is the reason we were able to continue racing for so long. We learned that if we had only stuck to keeping things entirely in-house, it wouldn’t have lasted.”

In the 500cc premier class in 1976, Suzuki took eight wins from ten races, limiting Yamaha and MV Agusta to one win each. With Suzuki’s RG500 turning them into a force on the grid, Yamaha revamped its rider lineup for 1977. American racer Steve Baker joined Cecotto in the 500cc class on a new YZR500, but Sheene rode the square 4-cylinder RG500 to a second consecutive title. While Baker was unable to take a race win, he was a regular on the podium and finished as the runner-up. Cecotto sealed two wins but suffered injuries, leaving him 4th in the points.

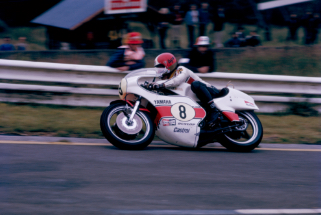

But Yamaha’s situation changed in 1978 with Kenny Roberts joining the team and being armed with the YPVS-equipped YZR500 (0W35K). Roberts had a dirt track racing background from his years in the AMA and a then-unique riding style in which he hung off the bike through corners. He also brought his own motorhome to each round, and in these ways, he slowly went on to change the norms of GP racing and its paddock culture.

Roberts’ exploits from 1978 onward are already well documented by the media, so there is no need to go into detail here, but his relationship with Yamaha can be summarized with his own words. After injuring himself in a crash during pre-season tests in 1979, Roberts was forced to spend a month recovering in the hospital. “That was when one of the Yamaha racing bosses came to visit me in the hospital and had a contract for me to sign. He told me that everyone was waiting for me to come back. It made me realize that Yamaha really cares about its people.”

Roberts returned to action at Round 2 in Austria that April, riding the second YZR500 to feature YPVS, the 0W45. He took the win and went on to victory another four times to claim a second consecutive premier-class title. He repeated the feat again in 1980, making it three titles in as many years.

In 1979, Roberts was joined on the grid by fellow factory Yamaha riders Cecotto and Frenchman Christian Sarron, also riding the 0W45 YZR500. The 0W45 became the foundation for the evolution of the in-line 4-cylinder YZR500 over six successive generations, from the 0W35, 0W35K and 0W45 to the 0W48 (aluminum frame), 0W48R (outer cylinders using rear-facing exhausts) and 0W53. It also served as the base model for the TZ500 production racer released in 1980.

The Formula 750 (F750) class officially became a world championship in 1977, and expectations were high that it could surpass 500cc as the pinnacle racing class. Yamaha entered with its YZR750 while supplying privateers with the TZ750 to energize the new series.

Yamaha released a new TZ750 featuring a Monocross suspension and other technical spec changes, and in the same way TZ models were sweeping the 250cc and 350cc GP classes at the time, the number of TZ750s on the F750 grid was overwhelming and there was no way for competitors to gain a foothold in the class. Yamaha thus won three consecutive titles in the F750 series with Baker in 1977 on a YZR750, Cecotto in 1978 also on a YZR750 and French rider Patrick Pons on a TZ750 in 1979.

However, the engine could put out up to 160 horsepower and the bike reached 300 km/h in testing, making it far too much performance for frames and tires of the time to handle. Plus, each rider’s points were calculated based on their best performances across the season, so teams with the leeway to race in more rounds had an advantage. This was why the series only lasted three years before it was scrapped.

Even so, Yamaha’s large-displacement 2-strokes continued to shine on the east coast of the United States. Before 4-stroke “superbikes” took over, Yamaha won an incredible 13 consecutive Daytona 200s, beginning with Don Emde in 1972 and ending with Roberts’ win in 1984. This utter domination made it nearly impossible to talk about the Daytona without mentioning Yamaha’s involvement.

Then in 1979, Honda returned to Grand Prix for the first time in 11 years, and with Suzuki also upping its own efforts, Grand Prix racing in the 1980s became a battle among the Japanese manufacturers for wins and titles.

Top