Challenges Carving Our Name into Racing History

A New Development Strategy and Promoting Grand Prix Racing for the 21st Century

Grand Prix motorcycle racing in the 1990s began with Wayne Rainey’s winning streak in the 500cc class, even while a steadily dwindling 500cc grid was breeding an air of instability in the paddock. To combat this trend, Yamaha made efforts to promote GP racing—while ultimately remaining dedicated to winning the title—by helping privateer teams participate in the premier class in order to safeguard the presence and prestige of GP racing as a whole. It was also around this time that development of the technological ideals underpinning Yamaha’s now-famous crossplane crankshaft engine were beginning to take shape.

In the mid-1990s, Yamaha had several less-than-stellar seasons in which the winning of 500cc titles drifted further out of reach. Despite the efforts of riders like the late Norifumi “Norick” Abe—who Valentino Rossi later called his idol—Yamaha was unable to secure a title for some time. Nevertheless, a number of factors, including the transformation of Yamaha's factory development division, intertwined to enable Yamaha to push forward into the 21st century and a new era of motorsports success.

Wayne Rainey’s Success and Yamaha’s Engine Development Ideals (1990–)

Although the YZR500 had been making progress season by season up to that point, when American racer Wayne Rainey rode it from 1990 onwards, the machine seemed to evolve just as quickly as Rainey’s winning streak did. Worthy of special mention during that time was that the engine of the YZR500 (0WE0) that Rainey took to his third consecutive title in 1992 laid the foundations for what Yamaha today calls its “crossplane engine.”

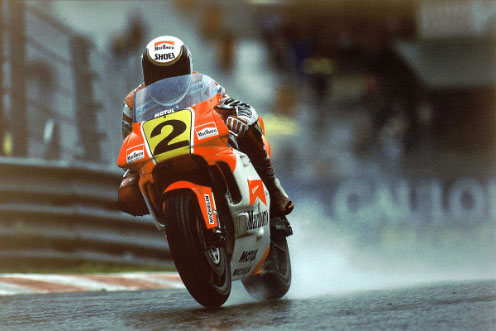

After riding for the Lucky Strike Yamaha team in 1988 and ‘89, Rainey switched over to the Marlboro Yamaha Team in 1990. In his first year with the team, he racked up seven wins to take the title with a sizable points margin over Suzuki rival Kevin Schwantz. The following year, he battled with Honda’s Mick Doohan, taking six wins and finishing on the podium in 13 of the 14 races, thus taking his second consecutive title in a strong display of riding prowess.

In 1992, Rainey was aiming for his third straight 500cc title. Doohan was in strong form early in the season, winning four races back-to-back and opening up a large points advantage over Rainey. However, Doohan suffered an injury at Round 8 and during the four subsequent rounds he missed, Rainey was able to claw his way back in the point standings, surpassing Schwantz to take over second place in the title hunt and closing the gap to the Australian. Doohan held a narrow two-point gap over Rainey going into the final round of the season at Kyalami Circuit in South Africa. The title battle went down to the final lap and Rainey finished 3rd while Doohan took 6th, earning the American his third 500cc title in a row.

The 1992 YZR500 that year had also gotten a boost to its competitiveness, going from 155 horsepower to 160 horsepower. From Round 9 in Hungary onward, the engine used uneven firing intervals. Its torque development characteristics were produced from the resultant combined forces of the combustion torque and the inertial torque from the rotating crankshaft.

Up to that point, the opposed cylinders of the YZR500’s V4 engine adopted a 180° even firing interval, but starting from the Hungary round, they used an uneven firing interval at 0° and 90°. This improved traction in the low- and mid-speed range and enabled greater power when exiting corners. The point of focus was a linear torque character, which can be seen as the same development goal as Yamaha’s later crossplane engine.

Rainey’s momentum continued to build in 1993 and a fourth straight title was in sight, but at the 12th round of the season in Italy, he high-sided his machine and crashed. His back was severely damaged and he was forced to end his season at that point. Rainey returned to the paddock the following year in 1994 but in a wheelchair. He established Marlboro Yamaha Team Rainey and was instrumental in the success of Japanese racers Norifumi “Norick” Abe and Tetsuya Harada before his retirement in 1998. Rainey was another of the great legends of the 1990s who inherited and passed on Yamaha’s Spirit of Challenge.

A Strategy for Promoting 500cc GP Racing (1991–)

In 1990, fans were anticipating a closely-fought 500cc season between American racers Eddie Lawson, who had returned to Yamaha, Wayne Rainey, who was out to win his first title, and Suzuki ace Kevin Schwantz. The result was the previously mentioned 500cc title for Rainey, but for GP’s premier class, an unfortunate reality was casting a shadow over the championship.

Compared to the nearly 30 machines that had lined up for the opening round in Japan in previous years, only 26 took part in qualifying practice in 1990 and by Round 2 in the United States, that number was only 17. Even in the main European rounds held in Spain, Germany, Austria and others, there were less than 20 machines on the grid. As factory bikes packed increasingly more performance, their price tags also rose, making it difficult for privateer teams to obtain the bikes they needed to compete.

Although Yamaha won the title, they also knew that this situation had to change and from 1991 onward, Yamaha began to lease YZR500s to prominent teams. Leases to non-factory teams were not only exciting for the riders but also inspiring for mechanics. Numerous mechanics said that the chance to do setup and maintenance work on a factory Yamaha machine was, while nerve-racking, an extremely valuable experience. With the goal of revitalizing the grid even more, Yamaha took this idea a step further and began selling 500cc GP engines.

This move was announced in September 1991: “We have made the decision to offer for sale 500cc engines for road racing with the aim of further revitalizing the Road Racing World Championship Grand Prix and the All Japan GP500 series. The YZR500’s V4 500cc engine will be available for purchase and the first parties in mind are prominent constructors in Europe.” It was announced that 10 units would be offered for sale starting in January 1992.

From 1989, Yamaha had also begun taking part in Formula One as an engine supplier. The team there was structured as a partnership between the engine supplier and constructor, and Yamaha took a hint from this way of doing things.

Positive results were soon apparent. In 1992, 23 machines—an incredible 60% of the grid—were YZR500s or bikes powered by YZR500 engines. Before the final round, Yamaha team manager Kazunori Maekawa said, “We’ve been working the past few years to revitalize the 500cc class, and to see so many entries here at the Japanese GP is fantastic. With ROC, Harris and other European manufacturers participating, I think the fans will enjoy it a lot. The series will come to life even more if constructors from each country and region continue to bring out their originality with new ideas and ingenuity, and these machines will surely continue to mature.”

That momentum continued into 1993 when the revival was clear with an average of 33 entries in the premier class. When the season concluded, a total of 29 riders on YZR500s or with YZR500 engines had scored series points.

Taking Command of His YZR500 (1996–)

Even though the cherry blossoms in the Kanto region had already fallen, the colder winds from the west had kept some of the pink petals in the air at Suzuka and the 1996 Japanese GP got started in a dramatic flurry of sakura petals. Abe had qualified in 11th on the #9 YZR500, and after making a rocket start from the third row of the grid, he came down the main straight after the first lap in 4th place.

Abe’s challenge to compete in the 500cc class had begun in April five years prior. After graduating from junior high school, he had to wait five months until he was old enough to obtain a racing license from the Motorcycle Federation of Japan. During that time, he tried dirt track racing in the United States and learned how to drift the bike. At 16 years of age in 1992, he rode a TZ250 in the Super Cup Championship’s Eastern Series NA250 class, finishing it as the runner up. When he turned 17 the following year, he rode a Honda NSR500 in the All Japan 500cc class and beat out more experienced riders to win the title as a rookie. He was offered a wildcard appearance in the Japanese GP the next year, where he featured at the front and hounded Kevin Schwantz, thrilling the home crowd at the track and the television audience. While he had an unfortunate crash and did not finish the race, his electric riding style instantly won him fans around the world.

Abe’s road to a full-time seat in the premier class, however, was precipitous. It was in 1994 that the top racing class in the All Japan Road Race Championship switched from 2-stroke 500cc machines to 4-stroke 750cc superbikes, and Abe contested the series aboard a Honda RVF750 as he waited for his chance at a Grand Prix ride. The summer ended without Abe running at the front of these races, but it was then that the turning point in his career came. Marlboro Team Roberts’ premier-class rider Darryl Beattie had suffered a crash at the French GP and was unable to compete, so the team decided to give Abe a chance in the seat. Until that point, however, Abe had been widely known as a Honda rider.

On July 2, 1994, Yamaha’s PR staff brought a word processor with them as they boarded a bullet train from Tokyo bound for northern Japan. Their goal was to announce Abe ending his All Japan campaign in favor of riding for Yamaha in Grand Prix’s 500cc class. Inside a car in the paddock, a Yamaha PR officer and a Honda PR officer compared press releases for consistency before delivering them to the media. “For Honda, he was a prime candidate for a GP seat so they were magnanimous in letting him go to Yamaha,” was what some in the press said at the time.

Abe joined up with the team two weeks later at the British GP. He rode his first race on a YZR500 at the Czech Republic GP to a strong 6th place and did it again at the following United States GP. He competed full-time the next season and stood on the podium for the first time with 3rd at the Brazilian GP, but several crashes left him in 9th overall for the 1995 season. In the spring of 1996, however, when the series returned to Suzuka Circuit, things were different. The night before the race, Abe’s father shared what he thought would happen: “There’s only really two kinds of riding: Letting the bike ride you, and you riding the bike. Tomorrow, I think Norifumi will be out there riding the bike.”

Those words proved true, as Norick was truly riding the bike that day. He passed Mick Doohan for the lead on lap 8 and the Australian gradually faded out of contention. Honda’s Alex Barros and Takuma Aoki were beginning to catch him but then both crashed out, leaving only Alex Crivillé, but he was unable to match Abe’s speed. Even in the final stages of the race, Abe’s speed never faded and he lapped two seconds faster than his qualifying time before finishing almost seven seconds in the lead. That was how Abe seized the day to become the 15th rider to win on a YZR500.

Breaking Out of a 22-Race Winless Streak (1997–1998)

The 1997 and ‘98 seasons were something of a rough patch for Yamaha. After Italian racer Loris Capirossi won the final round of 1996 in Australia, the YZR500 went 22 rounds without a victory. Of the 15 rounds in 1997, Luca Cadalora took four podium finishes and Abe one, for a total of five podiums and no wins. It was the most lackluster season Yamaha had experienced since beginning 500cc competition. “Norick and Luca’s riding styles are different, so what they need from the bike is different too. That may have had an effect on development,” said some members of the team. However, that did little to assuage race fans who wanted to see Yamaha win again.

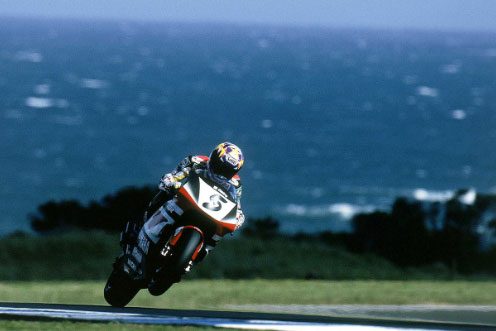

In 1998, Japanese GP wildcard rider Noriyuki Haga fought bravely to take a 3rd place finish at Suzuka, but over the course of the season, a Yamaha win still seemed like a distant prospect. But it was Simon Crafar from New Zealand that helped fight back against that mentality. He had made his 500cc debut on the former Harris Yamaha team before becoming active in superbike racing, and then joined the Red Bull Yamaha WCM team in 1998. He placed 3rd in Round 7 at the Dutch TT and took pole position for Round 8 at the British GP. Fighting on equal terms with Doohan and Abe, he not only set the fastest lap of the race but also came past the checkers first, becoming a 500cc race winner. For Yamaha, it was the moment that a 22-race winless streak in the premier class finally came to an end.

From the start of the 1990s, Yamaha had supported Grand Prix racing by supplying YZR500 engines to privateer teams, which gave many riders a chance to compete and grow. And in turn, those riders who had honed their skills on such teams became the key to Yamaha’s factory team winning again. Even so, 1997 and ’98 were tough seasons for Yamaha, with Honda locking down 1st through 5th in the final points standings both years.

Biaggi Joins Yamaha as 4-Stroke Development Continues (1998–)

After the 1998 season, when cold weather had already descended on Japan, a lone Italian got off the plane at Narita International Airport. When he proceeded to the counter to purchase a train ticket, the clerk could not hide his surprise: “Whoa, you’re Biaggi!” At the time, Massimiliano “Max” Biaggi’s switch from Honda to Yamaha was widely known in Japan. In preparation for the 1999 season, Biaggi changed trains at Tokyo Station and boarded a bullet train to Shizuoka Prefecture, heading straight to Yamaha’s test track.

Fans had big expectations of Biaggi, as he had the pedigree and potential of a four-time 250cc World Champion. In 1999, he scored his first podium finish for Yamaha at Round 3 in Spain but then suffered injuries and was unable to get into a strong rhythm for the next run of races. But after the summer break, he came back with renewed energy. After finishing in 2nd in Australia, he took his first win for Yamaha at the next round in South Africa, then finished in 2nd again at the remaining two races of the season for a four-round podium streak. This gave him 4th overall in the points and despite a relatively restrained season, he was preparing to make a strong statement in 2000.

At the time, Yamaha had another job behind the scenes. The 500cc era was coming to an end and as 4-stroke machinery was set to take its place, Yamaha’s development priorities began to shift. One of the engineers at the time spoke about the reasoning behind this shift: “Before, developing the 500 was the highest priority while production-based 4-strokes were secondary, but with the new era approaching in the late ‘90s, we had to consolidate these two priorities into one.”

Yamaha’s full-fledged 4-stroke factory participation began on March 10, 1985 at the Suzuka 2&4 Race. The entry in the TT-F1 class was the FZR750 based on the FZ750 production bike and Japanese racer Shinichi Ueno started from 2nd on the grid for the race. He finished 8th due to some machine issues, but he was running in 3rd midway through the race and when he began closing in on the two machines in front, it highlighted the strong cornering capabilities and potential of the machine. At the Suzuka 8 Hours race the same year, Japanese rider Tadahiko Taira and American Kenny Roberts formed a veritable dream team aboard the FZR750. Though they ran away with the lead for most of the race, the bike developed a problem in the final 30 minutes and the pair had to retire from the race. This dramatic end to their 8 Hours challenge—as well as their demonstration of the FZR750’s potential—brought a roar of cheers from the nearly 200,000 fans in attendance.

“With the arrival of the FZ, our 4-strokes were finally able to compete head-to-head with our rivals,” recalled one Yamaha engineer. However, the reality was that the potential within the FZ750 and FZR750 was not just on par with the competition—it surpassed them. The following March, Eddie Lawson competed in the 1986 Daytona 200 on a factory-tuned FZ750 to take Yamaha’s 17th win at the event after a two-year drought. Yamaha also took to the top step of the podium at the Suzuka 8 Hours in 1987, 1988 and 1990. Unlike Honda’s V4 engine, Yamaha had pinned its hopes on the potential of an inline-four engine layout.

When the first-ever season of the Superbike World Championship began in 1988, the main 4-stroke race series began to shift from TT-F1 to the new “superbike” class. One major development regulation difference between the two series was that the engine’s center of gravity could not be altered for superbikes. This was where Yamaha saw an opportunity and joined the Superbike World Championship in 1995 with a full factory entry. The roster for the Bol d’Or the previous year was Japanese racer Yasutomo Nagai and French brothers Dominique and Christian Sarron, and the trio won the iconic event on the YZF750.

This is how Yamaha’s knowledge and experience gained through 4-stroke factory machine development since 1985 was eventually combined with the 2-stroke 500cc development team. The mission of this new group was to develop the YZR-M1 for the new MotoGP World Championship. The team manager at the time shared his thoughts: “I wanted to start with a YZR500-derived frame as a base to build the rest of the chassis. Considering the type of 4-stroke that could be mounted in that frame according to the new MotoGP regulations, we concluded that an inline-four was the best choice.” In 2002, Max Biaggi—then in his fourth year with Yamaha—won MotoGP’s first-ever Czech Republic GP, also giving Yamaha and the YZR-M1 their first victories in the new series. It was the first step in Yamaha’s march to MotoGP frontrunner status in the mid-2000s.

Top