The Hurdles in Bringing Sporty Performance to a Big Naked

(Return to Part 1)

The “naked model” boom was not limited to the 400cc class and soon spread to the big-bike category as well. This was due to Kawasaki releasing the Zephyr 750 and 1100 in quick succession, followed by Honda introducing the CB1000 SUPER FOUR (also known as the CB1000 BIG-1) as the top-end realization of the CB400 SUPER FOUR’s image. Yamaha also responded by starting development of the XJR1200 soon after it had completed the XJR400.

“As with the XJR400, we did thorough research on the offerings our competitors had released before us,” says Yoshitaka Kojima.

“The Zephyr 1100 and the CB1000 were completely different in character. The direction the Zephyr took was a solid feeling of stability and it had a milder feeling to its performance; it really felt like a big bike. The first impression of the CB1000 was that it was big. The size was accentuated even by the fuel tank and the seat. But it was actually light and agile when you rode it. However, our perceptions as test riders told us that this degree of lightness and agility wasn't our goal. At Yamaha, we had the desire to build a motorcycle that had true over-750cc big-bike character, but we felt that if we went in the same direction as the Zephyr, we wouldn’t have the sportiness we wanted. That said, however, we thought that lightness on the level of the CB1000 would make it feel too light for a big bike. We had reached a sense of where our target lay and decided what we wanted the bike’s character to be.”

XJR1200 (Released in 1994)

The XJR1200 was developed as a model specifically for the Japanese market and was released in 1994. As stated in the article, priority was placed on handling performance in the practical-use range of the Japanese market, and the engine character was tuned in accordance with that aim. Furthermore, despite being a 1,200cc-class big bike, consideration was also given to sporty performance and thus a more compact riding position was set. The FJ-derived, air-cooled 4-cylinder engine had a bore x stroke spec of 77.0×68.3 mm, 1,180cc of displacement, a maximum power output of 97 PS at 8,000 rpm and maximum torque of 9.3 kgf·m at 6,000 rpm.

Unlike the XJR400, where the handling was developed to make the most of the engine’s fun-to-ride character, the approach with the XJR1200’s development was typical of a big bike: first deciding on the desired handling characteristics and then developing the engine character to fit that.

“We had been developing our big bikes until then to fit the needs of their primary markets of Europe and North America. But, since the XJR1200 was the first big bike we were developing to target Japanese users, we knew we didn’t have to run it on the Autobahn [like before]. That alone made things easier for us,” recalls Kojima.

For a long time, Europe had continued to be a market where big bikes without any cowling couldn’t win market approval, so the developers were now in a new situation where they only had to cater to the needs of users in Japan during development. By the way, after sales of the XJR1200 began in Japan, it was also exported to Europe and gradually grew in popularity there as well.

“But—although nobody said it officially—our honest feeling in the beginning was: how are you supposed to enjoy ‘sporty riding’ on the twisty mountain roads of a place like Hakone in Izu on a bike that weighs over 200 kg and has a 1,200cc engine? So, we actually rode some big bikes to the Izu Peninsula and ran them long and hard on the many winding roads there,” Kojima continues.

When you have a production model of such big size, power and torque, you can’t expect it to deliver its full performance potential on winding roads. But, their professed aim was to explore the possibilities of developing a big bike that would offer sporty riding fun for the Japanese market. As we look back on the project today, we realize that determining the performance character for a big naked model must have been quite difficult for a manufacturer making its first attempt to do so.

Getting the Handling Right through Engine Tuning

“I directed that the engine must provide plenty of torque in the actual range where it would be used the most, between 2,000 and 3,000 rpm. Basically, the goal was to achieve linear power delivery,” says Kojima. The air-cooled 4-cylinder engine for the XJR1200 used the engine on the FJ1200 model for Europe as its base. Since the FJ1200 had very-high-speed cruising as its top priority, its prerequisite was performance that could handle long, continuous use in the high-rpm range at or above mid-range speeds. This meant that the engine would require a complete reworking of its character to fit the XJR1200—much more than simply altering some settings and the like.

“We concentrated development on power output in the low- to mid-speed range because that would be the main rpm range in use when riding the XJR1200,” Kojima continues. “The actual development process is a delicate one with a lot of areas of fine nuances. This is because the main determining factor for whether you feel a bike is heavy or not isn’t the weight of the machine itself but the torque characteristics of the engine. This particular aspect is so important that you can’t decide on the tire or suspension specs until you’ve gotten it where you want it.”

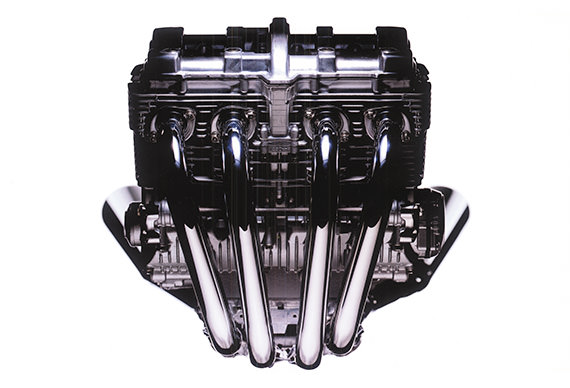

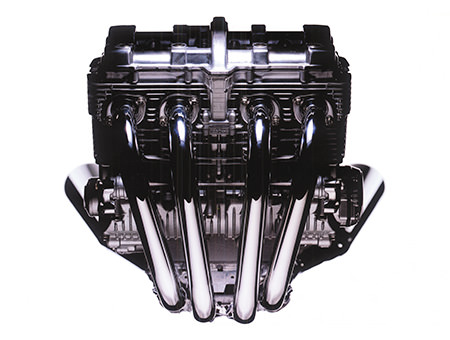

The XJR1300’s air-cooled 4-valve engine

(1998 year model)

In 1998, the engine displacement of the XJR1200’s engine was upped by 100cc to give it a maximum power output of 100 PS as the power unit of the XJR1300.

“People considering riding liter-class bikes are likely to go through the turns with the throttle partially open,” says Kojima. “So, the important part becomes fine-tuning the characteristics of the engine when applying throttle to accelerate [when exiting a curve] from the partial throttle opening you have entered the curve with. Of course, it can’t be a sudden jolt of power, and even if you make the delivery smooth, you still need to feel plenty of power.”

For a development staff that previously ran tests of performance primarily in the very-high-speed range, it was virtually their first attempt at pursuing an engine character that didn’t cause the bike to lurch forward, or pitch up or down every time the throttle was opened up from the low-rpm range. However, when we actually ride a big bike in daily use, it’s this type of throttle control in the low- to mid-speed range that is most important.

Kojima explains: “To get the bike to move the way we wanted it to, we had to get engine characteristics that made that possible. We ended up developing the handling by tuning the engine.

“For example, there are techniques like applying a bit of drag with the rear brake when making a U-turn in order to keep from losing balance if the engine response is too sudden and causes a jolt of acceleration, right? But with the XJR1200, we couldn’t allow performance that would require riders to depend on such techniques. It was not an easy task, but I enjoyed being able to spend time working to get exactly the kind of character we were aiming for. The development theme for the XJR1200 was more familiar and closer to everyday reality than the repeated trial-and-error process involved in developing racer replica models in the previously unknown realm of speeds around 260 to 270 km/h. Also, unlike the replica development where the opportunities to actually test at those speeds were limited, with the XJR1200, it was possible to try out and test things again and again [until we were satisfied]. The actual development time itself was about the same as for the replica models, but we were able to spend more time working on specific areas, and that made the process quite enjoyable.”

Reaching Even Deeper for Finely Tuned Performance

In addition to the development focus on low-speed range performance, a lot of time and effort was also spent on fine-tuning the handling to achieve a sporty feeling in the mid-speed range and up.

“Because the replica era had lasted so long, we hadn’t done development work on steel-pipe double cradle frames for some time,” comments Kojima. “Even though we had a proven unit in the lateral frame developed for the FJ machines, it wasn’t the type of frame that we could use, considering the looks of a naked model. So, we set about building a new frame based on its pipe size, aiming for a strong, robust unit that would provide the feeling of assurance we demanded. This time, the target was not a feeling of rigidity at 300 km/h but a tangible feeling of assurance [in practical use on public roads].

“Because our aim was to create a tangible sporty feeling with this model, the direction we took for the riding position was not a more relaxed one with freedom in terms of posture, but a more compact one.” Being built around a 1,200cc engine, the chassis was large, but through measures like narrowing the handlebar width, it was definitely a position aimed at rider-machine unity.

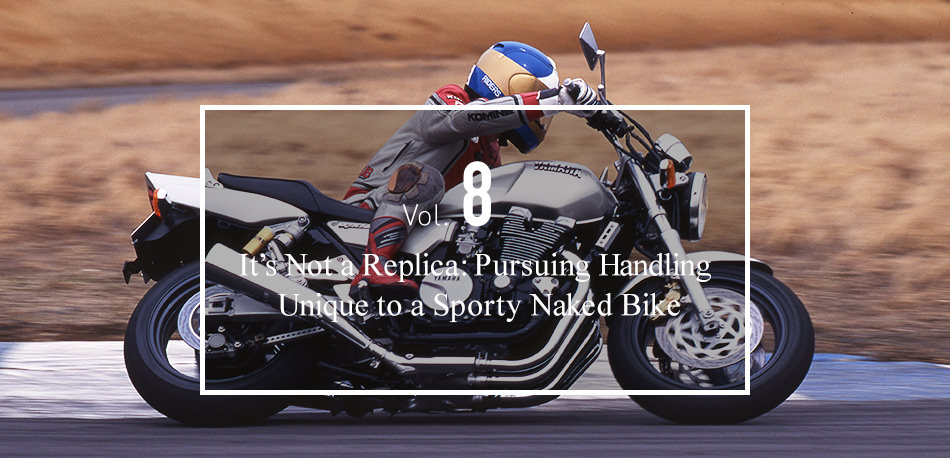

Ken Nemoto test-riding the XJR1200 (1994)

Kojima continues: “Compared to the light feeling of the CB1000, you can feel the greater stability in the XJR’s character. This was something that was set decisively and without any doubts among us, because everyone on the team shared the same perceptions [of the desired handling for the motorcycle]. As for the perennial debate about what was ‘too light’ or ‘too heavy,’ no one really had any objections about the handling we arrived at with the XJR1200. This was partly due to Yamaha motorcycles in general now having a lighter handling feel than in the past. Another likely factor was that a new generation of test riders took the lead with the XJR.”

Also, because the values the development staff would keep to in test evaluations were clearly defined ahead of time, it was agreed for example that 6,000 rpm was already quite a fast level for riding in Japan. In other words, that meant it was considered to be a level near the average rider’s limit. So for testing purposes, 4,000 to 5,000 rpm became the standard representing the central rpm range when an average rider would decide to pick up the pace and ride faster. The team would especially focus their perceptions and experience on this range in the fine-tuning work.

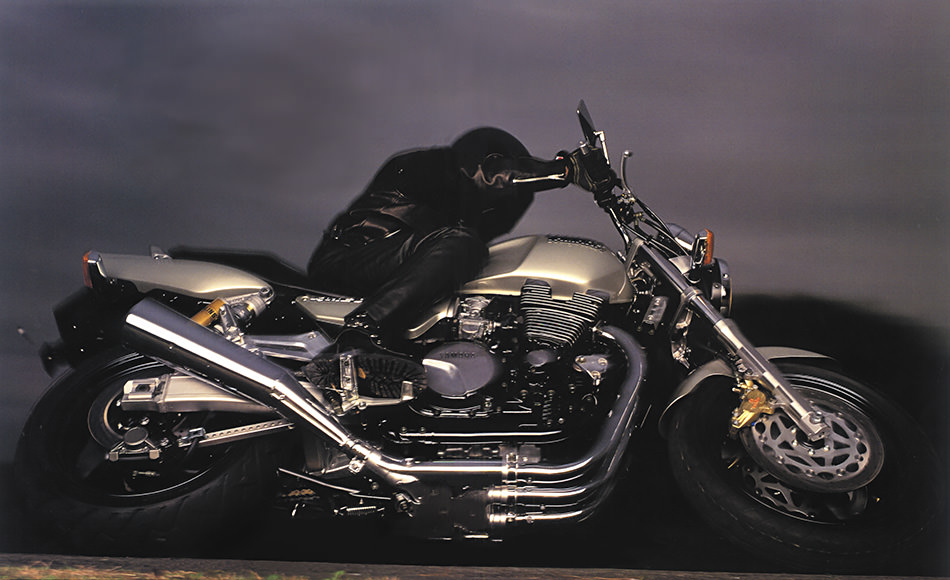

Magazine advertisement for the XJR1200 when it debuted

A photo emphasizing the model’s handling, and its form and beauty as a big, air-cooled naked bike

“For example, with regard to how the brakes perform, you could get the OK for a replica model simply based on runs on the test course,” explains Kojima. “The top priority would be on all-out braking power, and then you would work from there to fine-tune how it transitions for good usability. However, since the demands for a naked model included how the brakes feel in situations other than just hard braking, tuning the performance becomes a more delicate operation.”

It goes without saying that this kind of attention to detail is what led to the adoption of an Öhlins rear suspension. It was a case where achieving a level of performance that would satisfy the developers in terms of both the feeling of the ride and the sportiness they wanted—with a big, heavy bike with lots of torque no less—meant that the suspension also required top-notch, i.e. pricey components.

As a latecomer joining the ranks of the big naked category, the XJR1200 went on to win many fans and has secured a leading position as a popular bike that still holds firm today. When you see the way clearly experienced riders still get great pleasure from riding the big-bodied XJR1200 and enjoying the feeling of rider-machine unity it provides, you can’t help but appreciate the weight of the results the developers achieved with their determination to bring Yamaha Handling to the naked bike category.

Born of such efforts, the XJR has since undergone repeated model changes in areas such as greater engine displacement and revised handling performance, and it remains a proud part of the Yamaha lineup even today in the 21st century.

(Continues in Vol. 9)