Vol.2 Yamaha Handling The birth of a Legend.

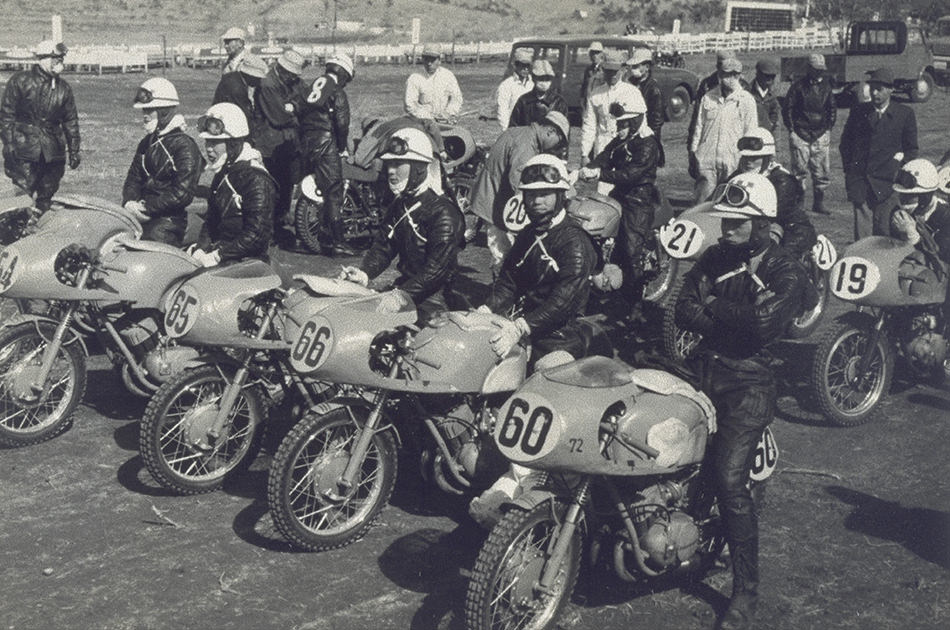

Yamaha’s strong involvement in racing is part of its brand image and one that can never be severed, no matter what the trials of the times may bring. Despite launching its motorcycle business later than other brands, Yamaha began its long history in the motorcycle racing arena with a resounding victory over Honda at the Asama Highlands Race in 1957. Yamaha then followed this up by heading overseas for its international race debut at the Catalina Grand Prix in the United States, and beginning full-fledged competition in the World GP in 1961.

Winning a world championship title didn’t take long, and until Yamaha temporarily withdrew from the World GP in 1968, the progress made by Yamaha’s factory machines was truly something to behold. Of course, while much emphasis was placed on dramatically increasing engine power, such as advances that drew 70 hp out of an originally 40 hp 250cc engine, Yamaha’s main development focus was different from its competitors. It was always about improving cornering performance and seeking ways to give the bike characteristics that made it easier to ride.

For this article, I took the liberty of investigating in detail exactly how Yamaha took the lead in handling performance, including testimonies from those that actually rode the bikes.

*The article below is a translation of a RIDERS CLUB article originally published in 1996 and contains additions and revisions.

Ken Nemoto

Born in Tokyo, Japan in 1948.

Withdrew from Keio University's Faculty of Letters.

He began riding motorcycles at age 16, won the 750cc All Japan Road Race Championship title in 1973 and competed in the World GP from 1975 to 1978. After returning to Japan, he served as the editor in chief of RIDERS CLUB magazine for 17 years and also served in producing a wide variety of hobbyist magazines. Today, he competes in the AHRMA's classic motorcycle races at Daytona Speedway as part of his life work.

The Chassis Development Knowhow Garnered From GP Machines

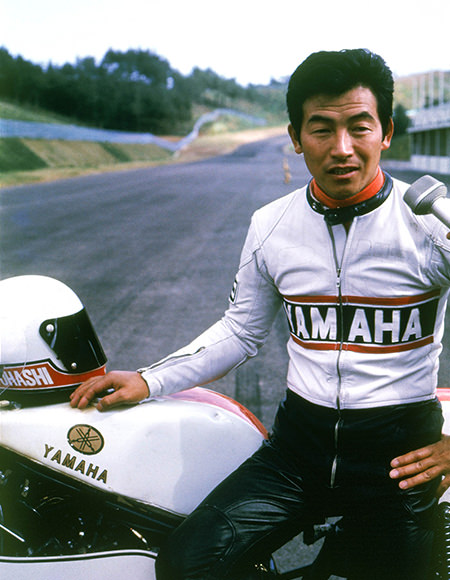

“Even back then, I thought of it as a kind of tradition, but you could say Yamaha certainly was a manufacturer that put a lot of importance on the rider’s evaluation,” recalls Akiyasu Motohashi,

a rider that any fan in that era of motorcycle racing knew.

Motohashi competed in World GP races in Europe as a Yamaha factory rider in the 1960s. He was one of my highly respected seniors and someone I looked up to when I was younger. He was a standout racer at the time because he was more of an intellectual and had graduated from university. I remember the final round of the World GP in 1966 at Fuji Speedway in particular.

While the other Yamaha factory riders were using the latest liquid-cooled 4-cylinder machines in the 125cc and 250cc classes,

a young Motohashi was the only one on the RA97 125cc liquid-cooled twin and the RD56 250cc air-cooled twin. But, he was still able to make bold moves to finish near the top. After Yamaha had to withdraw its multi-cylinder, multi-geared factory machines from GP competition, Motohashi still had a leader-like presence among the riders on Yamaha’s production racers during that era. He went on to have a famous showdown with Honda’s Morio Sumiya and Kawasaki’s Masahiro Wada, and as his junior in the same racing series, I asked him for advice numerous times.

At the 2nd Asama Highlands Race in 1957, Yamaha introduced and competed on

the newly developed 250cc YD Racer and 125cc YA Racer

“To Yamaha engineers, since the machine is ridden by a person, fulfilling the requests of the rider as much as possible was always the fundamental approach. Despite the often abstract requests of riders for ‘this’ or ‘that’ about machine handling, the engineers would always figure out some way to provide a solution, and they did so with incredible speed, too. Their teamwork was almost abnormal in the way they would all concentrate together on the work at hand,” said Motohashi. “When I entered the Yamaha team, I came to think of this as normal, but when I found out later how it was for riders on other teams, I realized that the relationship Yamaha had with its riders was something special. For other manufacturers, racing was more of an extension of the machine testing program and most of the riders that were on the track racing for them were test riders by profession. But, the only ones that could ride Yamaha’s race bikes were fully contracted racers.” When I asked him when he first “understood” handling, he said, “The first time I really ‘experienced’ what handling meant was with the 1962 TD-1. When I came down hot through the final corner at Suzuka on high-grip tires, the bike felt like it was flapping in the wind. When I went through on tires that weren’t so grippy, there were no problems and I put up a good lap time. That was when I first really understood the difference between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ handling.”

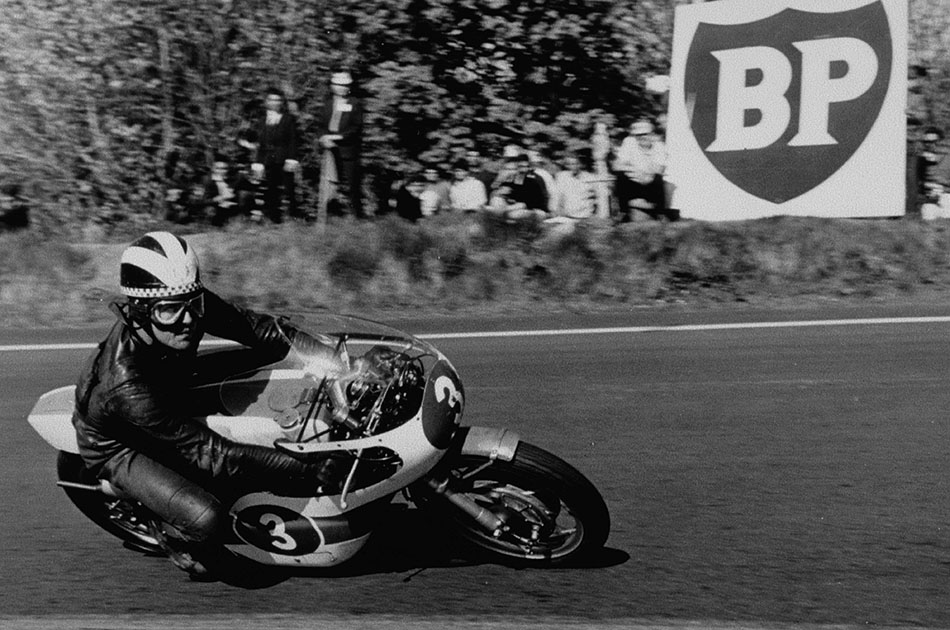

At the 125cc class Isle of Man TT in 1967, Phil Read (#10) took the win and Akiyasu Motohashi (#12) finished in 3rd

His words reconfirmed what I had thought; the riders that were actually racing on those bikes of the time knew the importance of handling. Yamaha’s engineers listened to their comments and built up their knowledge and expertise of motorcycle handling from early on. The RD05 that came out a few years later represented the full embodiment of the knowhow they had gained. As Yamaha’s first 250cc 4-cylinder race machine, the handling problems that inevitably emerged were solved with specific countermeasures that were steadily implemented on the bike.

Motohashi continued: “The RD05 had good power from the switch to four cylinders, but that also made it heavier and it had handling problems of its own; the air-cooled twin RD56 was sometimes actually faster around the track.

The decision was made to revise the RD05 from the ground up. It was made more compact and the center-of-gravity was lowered. The result was the RD05A. The former image of this model as a 250cc bike with a big frame like a 500cc bike changed to one that was compared to a 125cc bike. Yamaha really did everything to lower the machine’s center of gravity. However, making it too low resulted in the footpegs and other parts of the bike scraping the asphalt in the turns. It was easier to simply raise the mounting position of the engine to make sure the bike doesn’t scrape the track. Yamaha did all they could to lower the bike, and the footpegs and the undercowl would sometimes scrape the track surface. If you moved your boots off the pegs just a little, the tips would begin to grind off.”

Phil Reed (pictured) and Bill Ivy rode the lighter and more compact 250cc V4-powered RD05A in 1967 to six wins in the Road Racing World Championship.

Thinking back on it, the aluminum undercowls on the TR-3 and TZ350 I used to race would also scrape the track. The cowls were fit so snugly with the engine that it was like they were touching, and despite knowing that the cowls would scrape the asphalt, Yamaha lowered the center of gravity anyway.

“Now that I think about it, the RD05 was also fitted with a mechanism that made the caster angle adjustable. They didn’t alter the wheelbase but instead made it possible to adjust the caster angle for low-speed or high-speed corners.”

This surprised me because I’d never heard of such a device; the pursuit of handling performance had already come this far by 1965 and 1966. This was surely one of the main reasons Yamaha’s cornering performance was so good back then. “Yamaha was definitely fast in the corners. Even when most of the other manufacturers had switched to 4-cylinder bikes, the 2-cylinder 125cc RA97 was still competitive. The deciding factor was the torque Yamaha engines had. Everybody else was ignoring torque and aiming for top speed, so their powerbands got narrower and they had to add more transmission gears to use those narrow powerbands. Yamaha’s focus was always on good corner exit acceleration, and the key to having a high corner speed was to have the torque to power out of that corner. Some manufacturers fielded machines with 12 gears, but the RA97 started with 8 and ended with just 9.” This battle in the 125cc class saw 4-cylinder machines from Suzuki and Kawasaki with 14 gears facing off against Yamaha’s RA31 and its 9. When I started racing, I was with a Kawasaki-based team and I watched my seniors struggling to ride machines with redlines over 15,000 rpm but with a powerband less than 1,000 rpm wide using 14 gears—what an incredible difference in machinery from Yamaha.

(Continue to Part 2)

Akiyasu Motohashi test-riding a race machine